This post is also available in:

Honor to the merit of an artist who has been able to educate the public on women’s art, setting it in history with the respect it deserves. A Purple Poem for Miami was much more than the smoke and fireworks that Judy Chicago gave the city of Miami with her smoke-performance, among her most famous works. The work, organized by the ICA and sponsored by Max Mara crowns Judy Chicago on the Miami scene, with the participation in Art Basel and with the exhibition of a solo exhibition that covers forty years of history: Judy Chicago: A Reckoning, open until April 14th at the ICA. In addition to the strength of her works, the exhibition highlights the passage from abstract art to figurative art and above all its explosive force that has earned it the pioneering term of artistic feminism, honoring its place in art history. Many works that have represented the various pieces of which her artistic history is composed: from the minimalist colored sculptures to the feminine ones, to the hoods of cars, to the designs of the Birth and Holocaust projects passing through Powerplay to concentrate on the work proposed for the first time in the ’60s that brings it back to the days of the Atmosphere of Pasadena when she dressed the colors of the Californian air and admits: “The idea of being able to do something like this today, without asking for authorization, would be unthinkable”. A continuous succession of purple, blue, red and pink volumes, which followed one another for a total of 5 minutes of performance, in a surreal crescendo of colored volumes and fumes, which completely enveloped Jungle Plaza and its guests rushed to celebrate the beauty and rebellious genius of Judy Chicago.

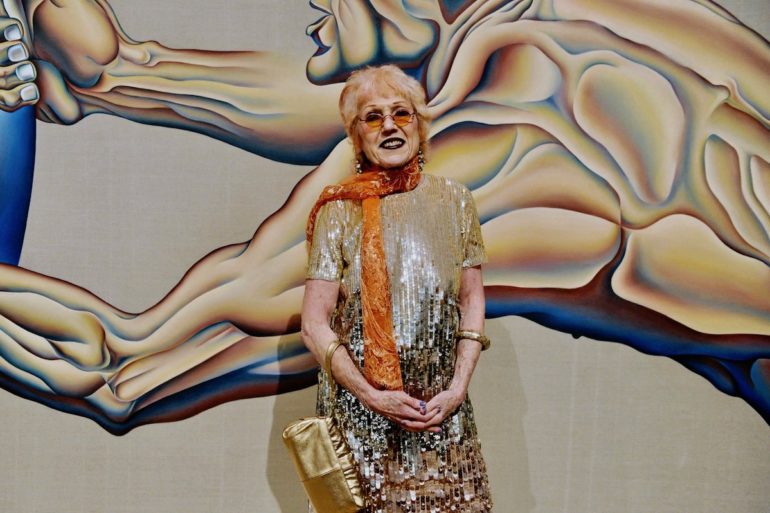

Subversive and multidisciplinary artist, Judy Chicago, in life seems not to let anyone condition her, and when she speaks there is to inevitably consider that the harshness towards life and rules, which emerges from her works, is inherent in everything she is part of: from the color of her hair shaded from white to purple, which changes regularly, to the ready and sparkling response to the shrill voice betrayed by the sound laughter. It is as if her rejection of rules and labels were dictated by her own survival instinct.

Yet behind the clear and subversive ideas of a feminine world that, thanks to women like her, is emerging there have also been great sorrows: the death of her mother and her brother more recently, but especially the death of her first husband after only a year of marriage following a traffic accident. An event that profoundly marked the art of Judy Chicago who suffered from it in despair for at least ten years.

Born in 1939 with the name of Judith Sylvia Cohen, Judy assumes the last name Chicago after having rebelled against the convention of the system according to which the father’s name is given to the birth of his children and that of their spouse once girls married. This process of re-appropriation of one’s own identity without gender distinctions will only be one of the steps taken in an all-male society in which women have little voice, especially in the artistic context. The initial works of Judy include a minimalist period of sculpture, in total contrast with the abstract expressionism of the time and different from the minimalism proposed by the peers Robert Irwin, Ed Ruscha, Larry Bell or Dennis Hopper. The squared and angular sculptures of Chicago are tinged with pink, red, orange, blue, green and pastel yellow in a feminine palette that contrasts totally with the squared, “masculine” lines of the composition (Trinity, Sunset Squares).

After completing her studies at UCLA with a master’s degree in Fine Arts, the years to follow are dominated by the engines that break into every scene of everyday life and with a decidedly masculine flavor. Taking note of the marginal role that women play in society, in the mechanical world in particular, Judy challenges gender and social classes by enrolling in a self-body-school course of 250 men in which she learns to paint cars with the use of spray cans. Thus, while the art of Al Bengston and Craig Kauffman is dressed in motors, Judy’s art is concretized directly on the car hoods with the representation of the uterus in an association of primary and secondary colors.

The spray will always have a dominant role in her art, even on the canvas, because as she says: “It is able to perfectly mix color and canvas”.

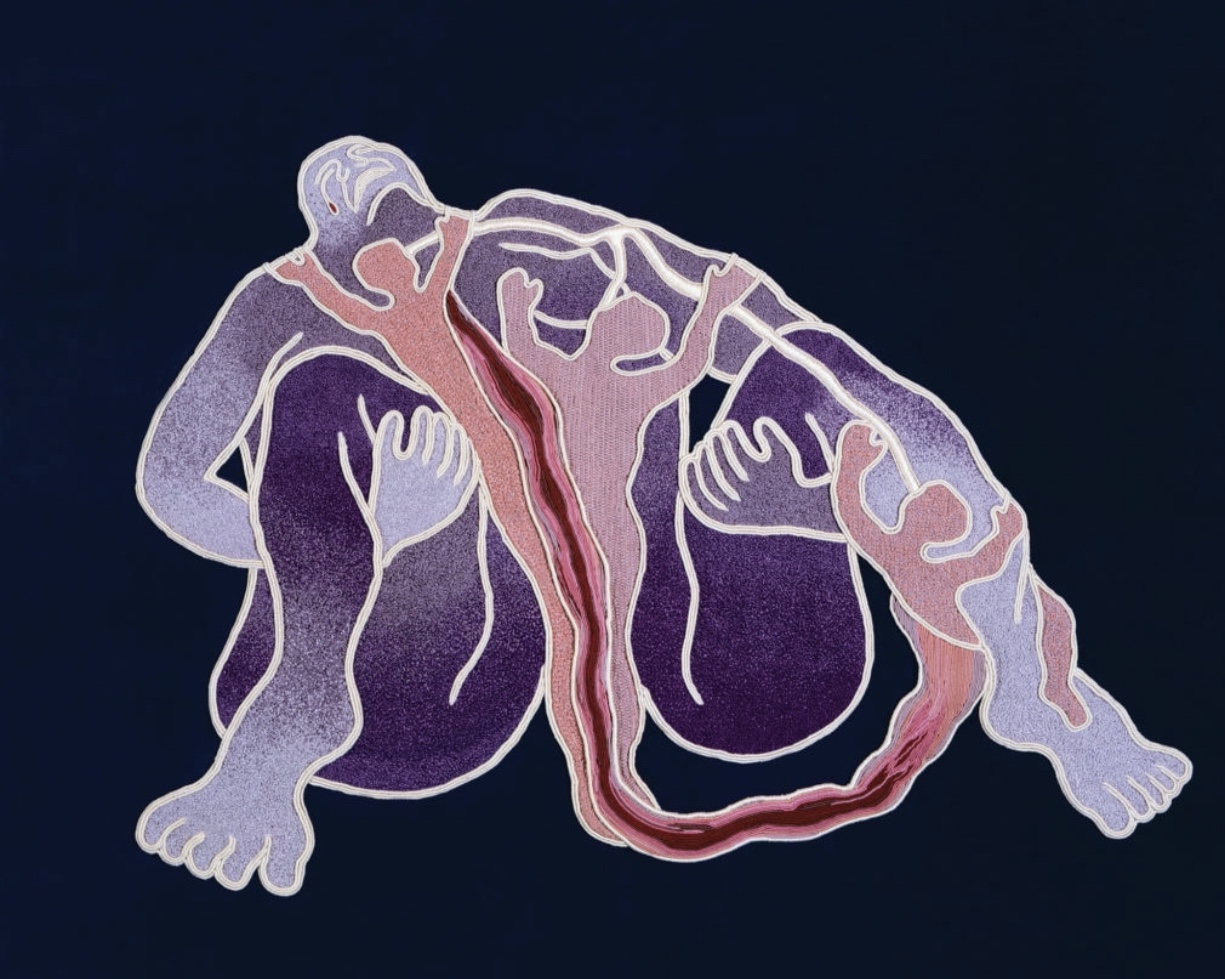

She began to produce large-scale works in the ’70s when participating in the exhibition “Female sexuality / Female identity” at the Womanspace gallery founded in collaboration with Miriam Shapiro, proposes the large canvases of Let It All Hang Out, Heaven Is For Men Only: a satire in the key of colors and shapes against patriarchal society. Reincarnation Triptych (Triptych of Reincarnation) is dedicated to three great writers of the past among the most prolific in the history of literature: Madame de Staël, George Sand and Virginia Wolf, with whom she celebrated the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of the feminist movement and a new piece in her artistic path. From the large works through The Birth Projects (1980-85) Chicago addresses the theme of religion by analyzing the Genesis according to which it is clear that a male god created a human male, Adam, without the involvement of a woman. According to Judy Chicago, the analysis of Genesis reveals a “primordial feminine self hidden between the recesses of the soul … the woman childbirth is part of the dawn of creation”. In the complex work, consisting of a hundred medium and large works, the artist involved 150 women, workers and mothers, who worked with macramé and quilt, to the works using threads with the same color gradient used as a base in the Chicago painting. Dramatic images in which birth scenes appear, for which the cry of pain, fleshly, becomes so intense as to lengthen the images to the point of deforming them and making the cry and the embroidery a whole.

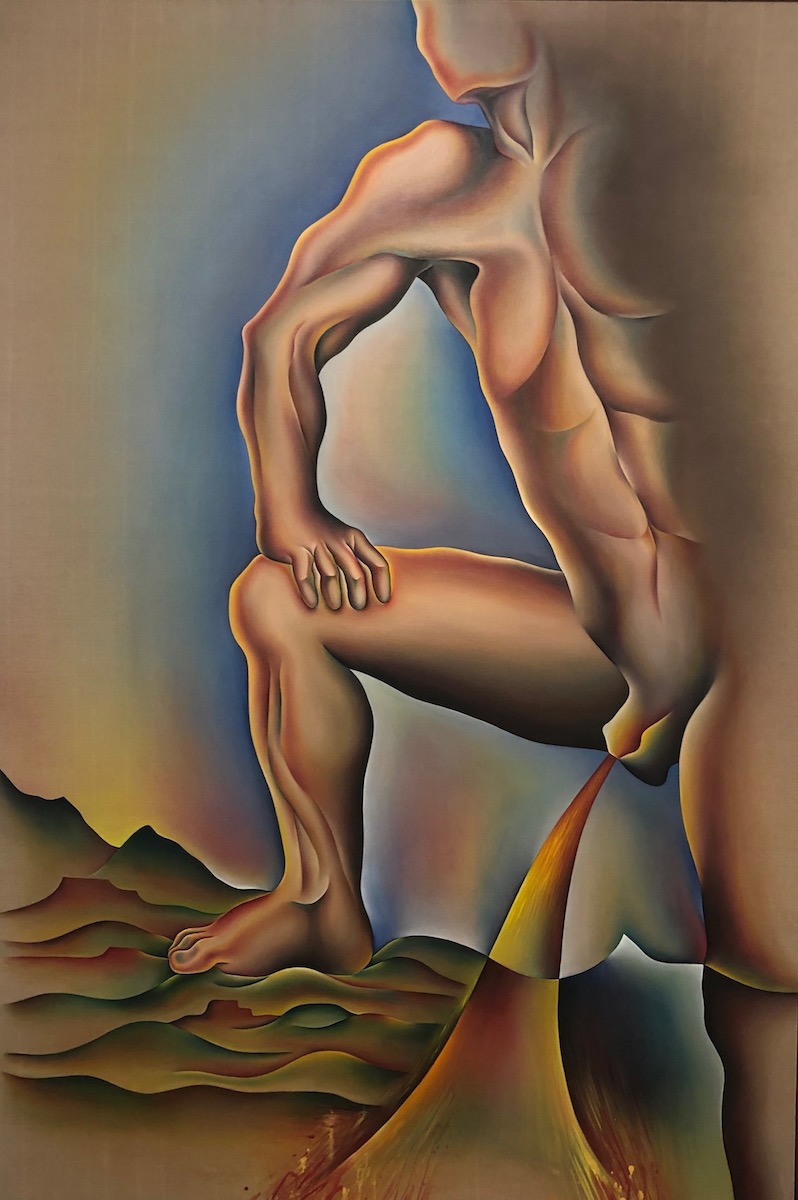

Inspired by the colors and luminosity of Renaissance paintings, is the series composed of drawings, paintings, plaits, coated paper and bronze reliefs by Powerplay (1982-87): The apotheosis of the refusal to the abominable masculinity of man who between abuse of Power and dominance over the female gender ends up overhanging the entire world without leaving survivors and destroying their beauty. The results is represented by strong and violent images, among which the image of a man urinating on nature, producing toxic wastes that inevitably contaminate the generations to follow, flagellating their existence.

In the Holocaust Project (1985-93), a four-handed work in collaboration with husband Donald Woodman, photographer, the spouses analyze the tragic event of the Holocaust, and of the inevitable confrontation with the Jewish religious teaching taught to her as a little girl. In the long question the spouses try to give answers to questions such as oppression, injustice and human cruelty, for which they will affirm that it was “a journey into the darkness of the Holocaust and out in the light of hope. It is based on a journey -intellectual, physical and emotional- that Donald and I have gone through… Addressing and trying to understand the Holocaust, however painful it may be, it can lead to a much broader understanding of the world we live in. Our hope is that this will contribute to an individual and collective commitment to undertake the vast project of transforming and nourishing our humanity, thus creating a more peaceful and equitable world”.

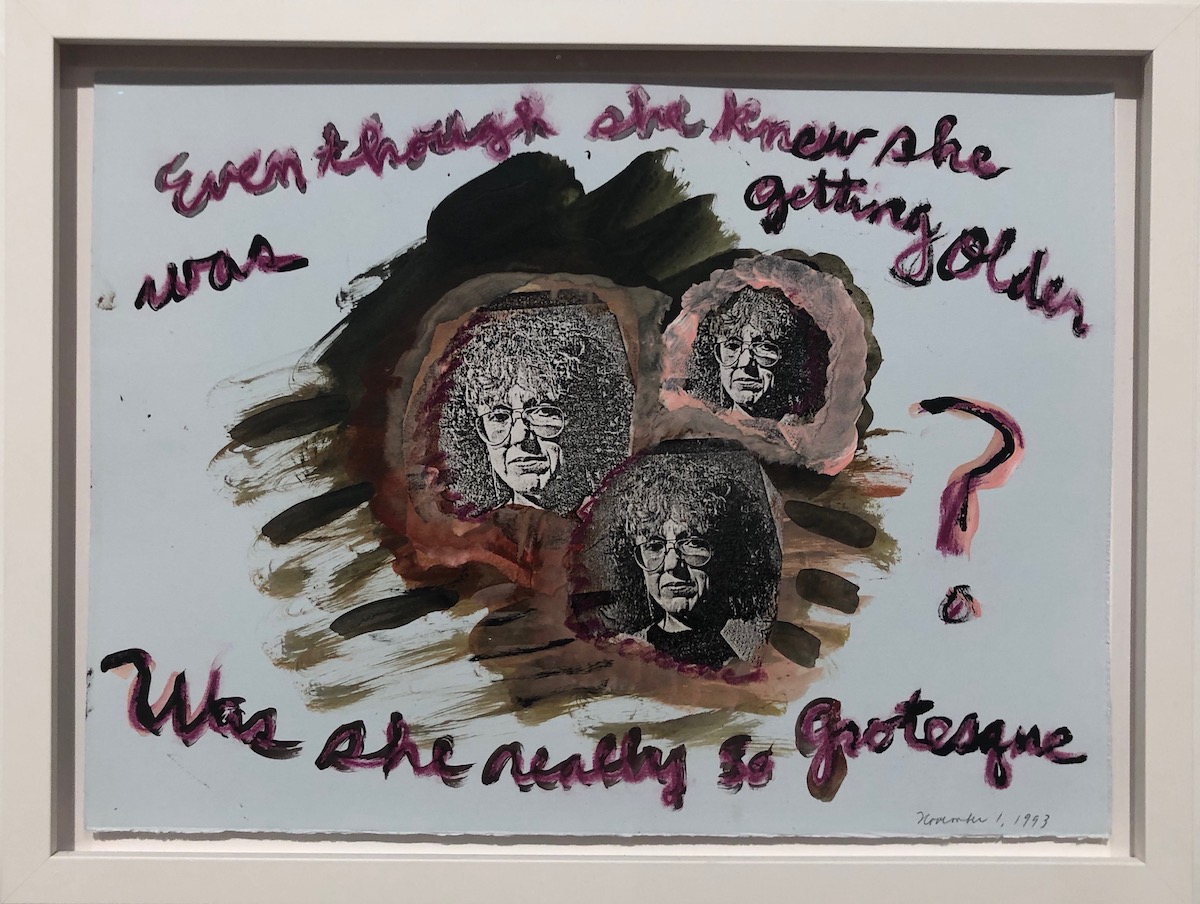

After being harshly evaluated by the critics, she moved to Belen, New Mexico, where locked in her bedroom, she tracks the big steps of her life, starting from when, as four-year-old girl, she was enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago to learn how to draw, all the way to adulthood and what maturity entails in terms of loss of affects and questions in reference to the individual and social self. The production is completed with 140 drawings that bring her back to her initial themes and that constitute works of Autobiography for a Year: Strong and harsh images that come out as a drawing on simple A4 sheets in which she exemplifies her existential crisis due to affective losses, insecurities in terms of a woman and artist with contrasting and frustrating emotions.

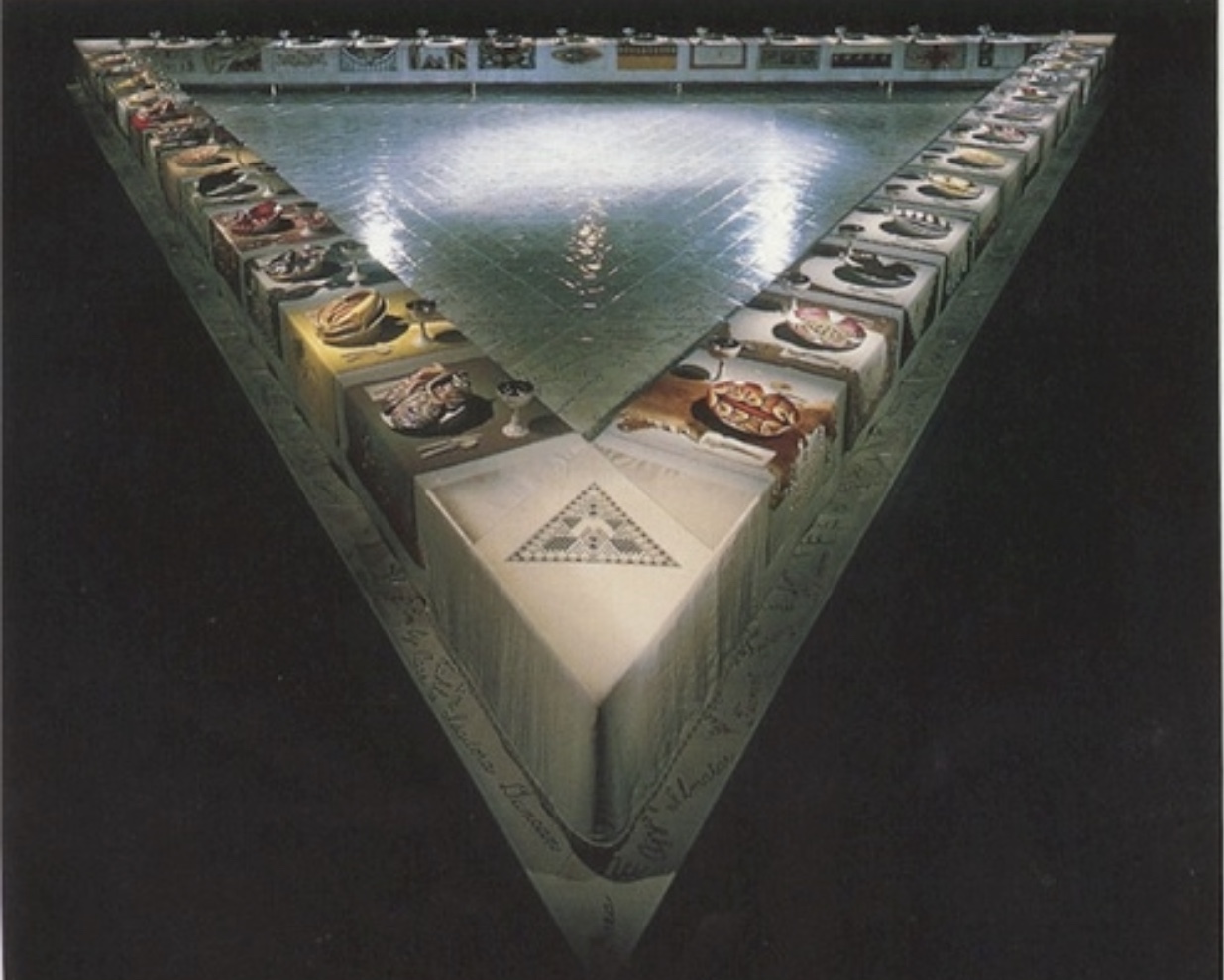

However, the undisputed masterpiece of Judy Chicago remains the installation The Dinner Party at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco in 1979. A milestone of the twentieth century, the work was seen by over 100,000 people, some of whom were present in the Lecture series of the ‘ICA in which Judy Chicago, interviewed by the director of the museum Alex Gartenfeld, has answered the questions of a loving audience who in previous years has participated in her works living in first person what was at the beginning of the’ 70s the first, true , artistic manifesto of feminism. The ambitious project, a sort of last female dinner in celebration of women who contributed to gender equality and relying on purely female work, required the intervention of 400 people and was exhibited until 2007 at the Elizabeth A Sackler Center for Feminist Art at The Brooklyn Museum. It consisted of a triangular table (the divine triad) of 15 meters on each side, on which appeared the names of the 999 women more than 39 (13x 3: the twelve apostles + Jesus Christ multiplied by the divine triad) represented with the post of honor to sit, among these appear: Georgia O’Keeffe, Queen of Egypt Hatshepsut, the Byzantine empress Theodora, the medieval nun Hildegard of Bingen, the American activist Sojourner Truth, the explorer Sacajawea, the painters Lavinia Fontana, Elizabeth-Louise-Vigée-Lebrun, Adélaïde Labille Guiard, Angelica Kauffman, Berthe Morisot, Paula Modershon-Becker Käthe Kollowitz, Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Cassat and Louise Nevelson, the photographers Gertrude Käsabier and Dorotea Lange and the sculptor Barbare Hepworth .

Richly set with the same silver cutlery, crystal goblets and fabric napkins, the peculiarity of the work, beyond the symbolic meaning, lies in the central processing of the porcelain plate made especially by Judy Chicago in a unique and characterizing way. : vaginas and butterflies are represented, symbol of liberation, mixed with the characterization of the character symbolically sitting.

A multifaceted artist who has ranged from painting to sculpture, from glass to ceramics, from dry ice to pyrotechnics, which has received numerous honors over time and which only recently have led her to exhibit her work in several exhibitions both in the US and in Europe. Her fame led her to be recognized in 2018 among the 100 most influential people according to Time Magazine and the most influential artist according to Artsy Magazine. She has been an artist, an art teacher and a book writer, but beyond the prodigies in the artistic field, Judy Chicago is credited with having subverted the order of the system for more than five decades, remaining firm in her commitment to the power of women’s art as a vehicle for intellectual transformation and social change and as women’s right to engage in the highest level of artistic production, a process that is not yet finished, but as she said in front of all those women who came to thank her for her commitment to guaranteeing female artistic work: “it leaves hope”.

.