This post is also available in:

Giovanni Segantini, 1858-1899, was a great Italian painter capable of revealing new artistic sensations that contributed to make his character a legend: he was in fact able to transform the negative events of his life into works of art. Born in Trentino Segantini was orphaned by his mother at the age of 7 and lost his father the following year. He lived his childhood in poverty and loneliness with great emotional deficiencies and despite being sent to live in Milan with his sister, he fled to end up in a reformatory, where a chaplain, noticing his skill in drawing, put him on evening courses at the Brera Academy.

His “suffering” life was the fertile ground on which he managed to harden his character and create the balance of his life both as a man and as an artist. At the time of his military service he had refused to serve under the Austrians (Trentino was annexed to Italy after the First World War) so he was forced to exile in Switzerland to avoid the death penalty. For Segantini, exile was another reason of punishment that he was able to turn in his favour: his forced isolation made his artistic works, which, unlike him, circulated in Europe, even more mysterious, and this factor fuelled even more his legend as a man devoted to nature.

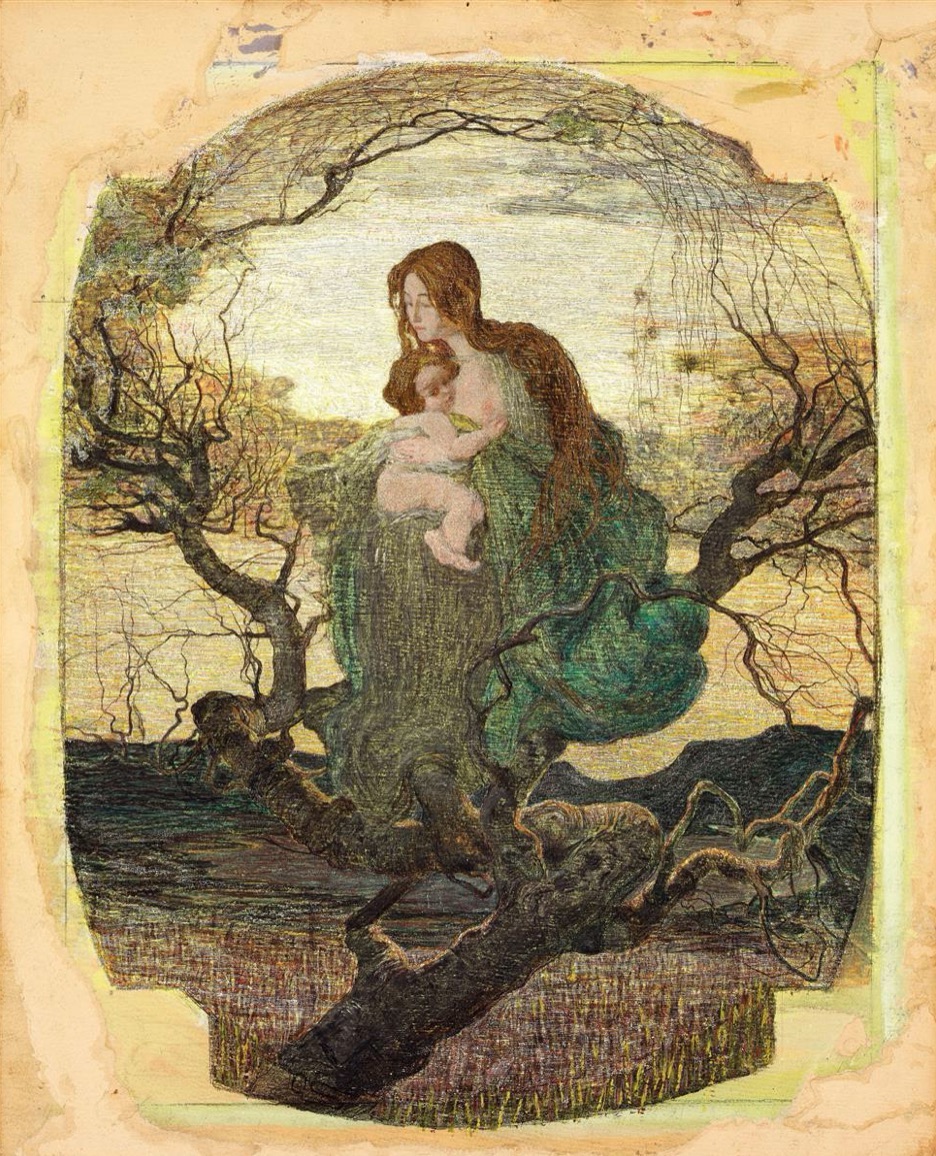

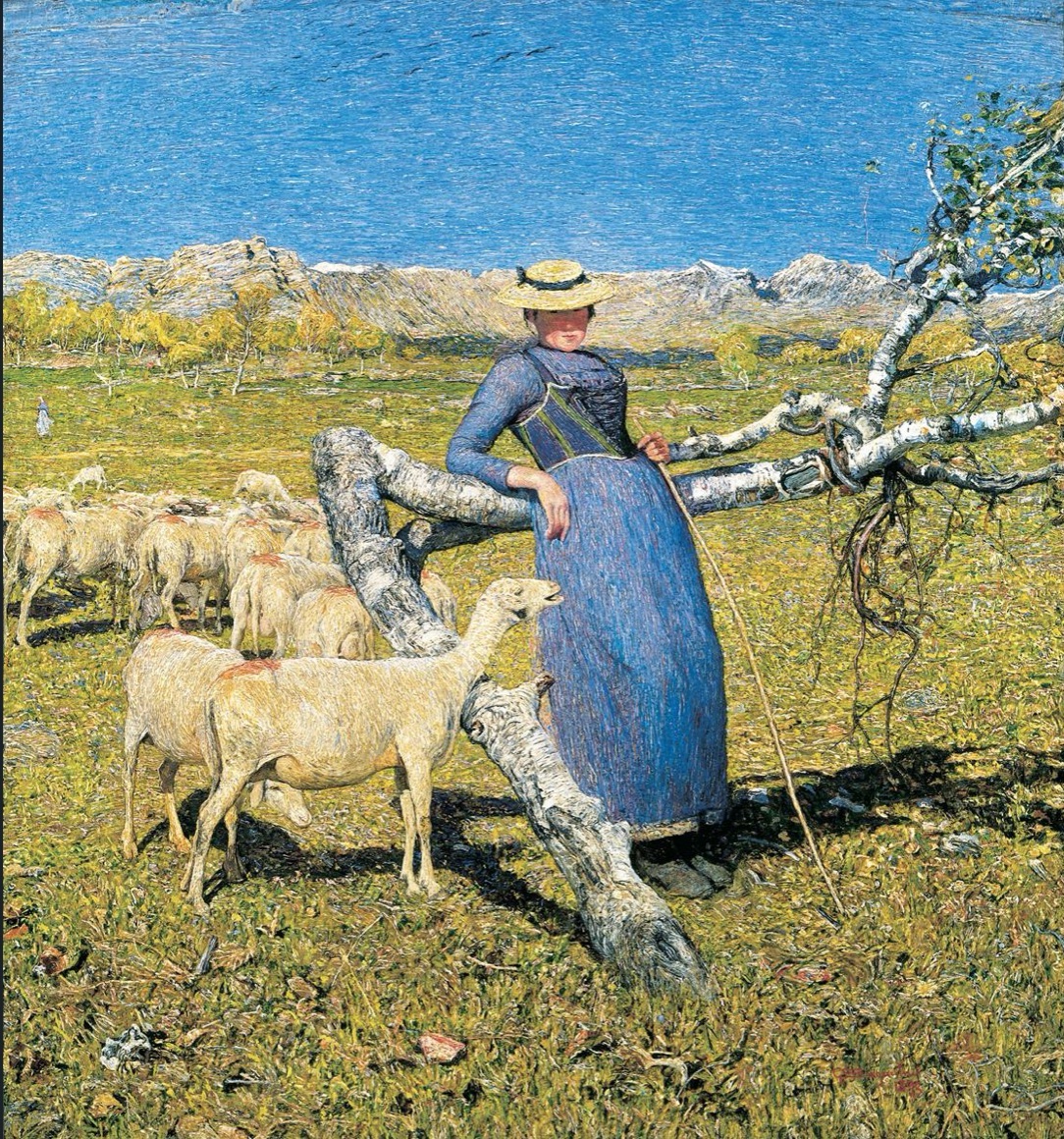

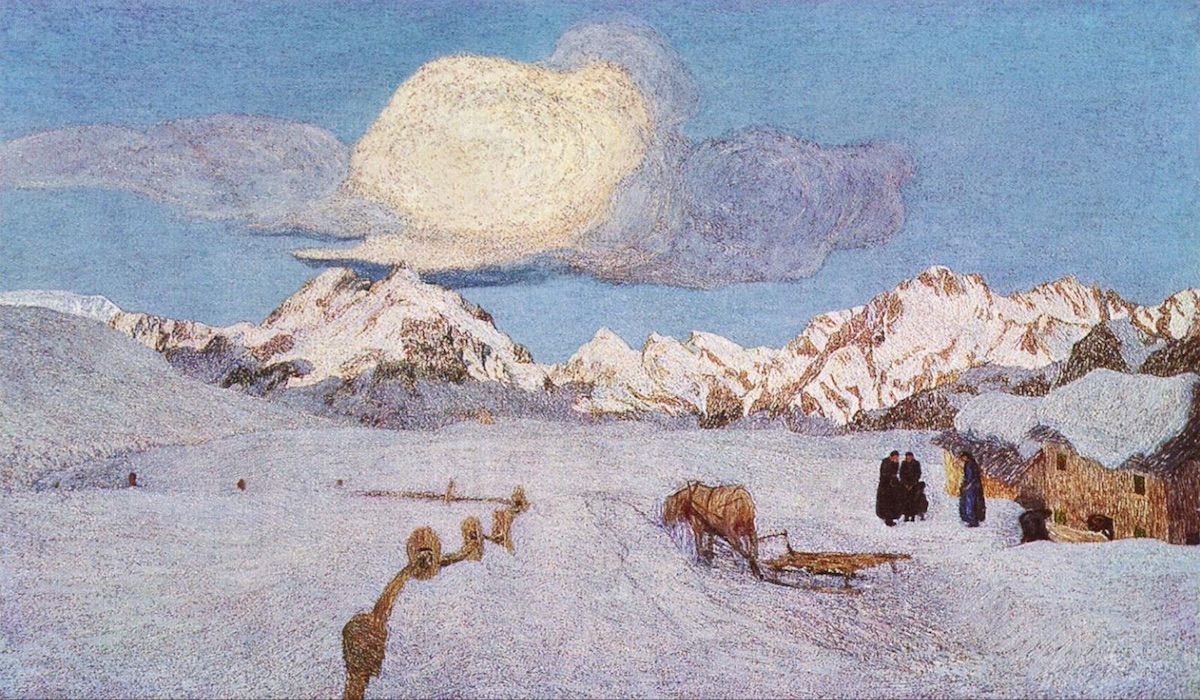

Segantini’s favourite artistic subject was in fact nature, followed by the representation of death. But if for death the pain of the survivors was the subject of the paintings, rendered through gloomy landscapes and silent blanket of snow, nature represented for Segantini the redeeming way on which to project his torment, imaginary and very rich, which was able to sublimate childhood traumas through art. Nature was also the fulcrum around which his artistic variations revolved: from tonal painting for the representation of the mists of Milan, through Symbolism, with the visceral identification between mother and nature, to the Divisionism with which he restored light to the alpine landscapes, which the artist carried within himself to the point of being defined “The painter of the Mountains”.

In his works Segantini never started from the concept to arrive at the image, but rather the opposite, given his dependence on reality: “What drags and fascinates my thoughts is the immense love I have for nature,” said the artist. Segantini’s farewell to genre painting comes with Italian Divisionism based in his works on “filaments of colour” arranged empirically on the basis of optical laws. Embracing Divisionism Segantini evokes the symbolism of rural reality in a very personal way: he illuminates the scene from a source of light opposite to that of the sun, obtaining a “reflector” effect that illuminates the shadows while remaining faithful to the chiaroscuro composition of the painting. Segantini, who used to paint from nature, almost always without preparatory paintings, was considered the greatest Italian forerunner of modern art.

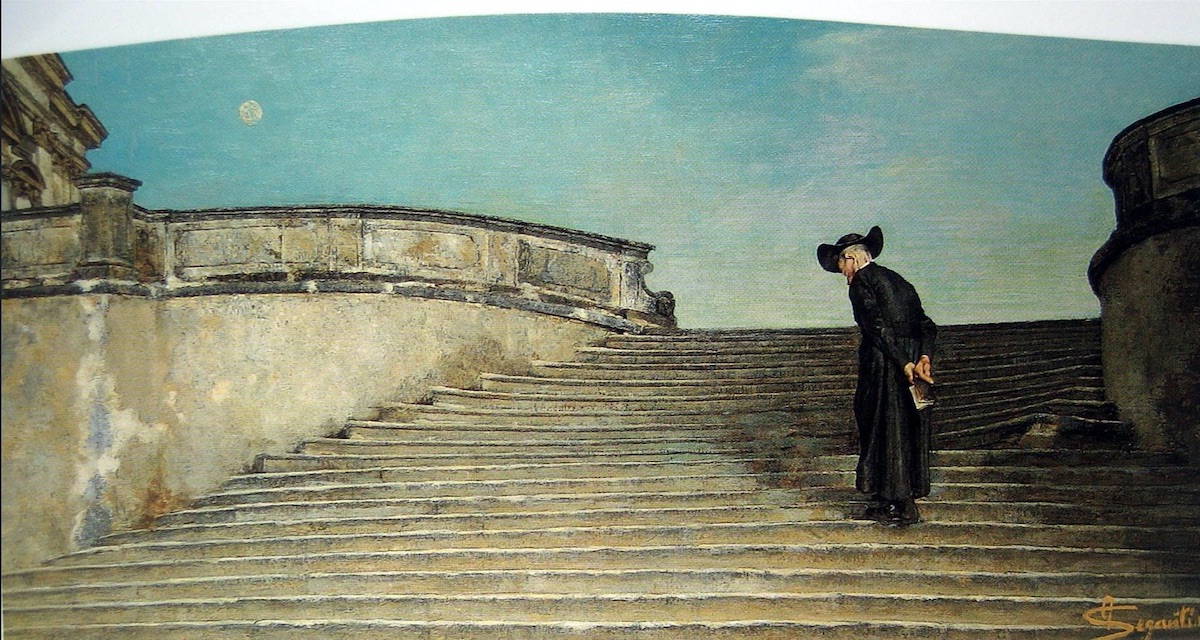

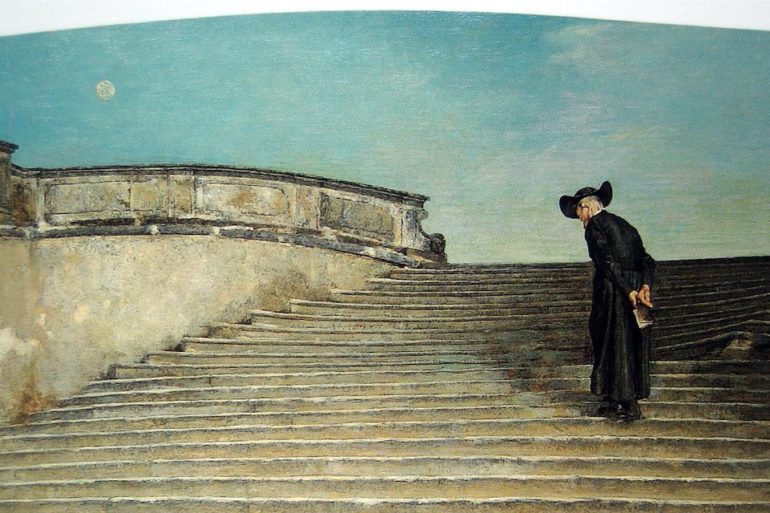

Thanks to his friend Grubicy, who supplied him with material during his exile, allowing him to be in step with the times, Segantini was able to know the realism from which he quickly detached himself because for him there were no social classes to promote but all individuals were equally part of nature and could be portrayed only if their torment found in his soul a personal answer. Segantini is remembered as one of the most famous and influential artists in Europe at the end of the 19th century and his paintings are part of important collections and museums including the Segantini Museum in Saint Moritz. The selected work was made by covering a previous work: “Mai Assolta” (Never Absolved), of strong anticlerical impact, made between 1882 and 1883 and visible today only at radiographic examination. The work, “an absolute masterpiece”, as defined by critics, marks Segantini’s farewell from genre painting.

The refined symbolism with which the artist represents a lonely and thoughtful priest climbing the stairs of the late baroque church of a Lombard village, absolved in his silence and solitude seems to question the fact that the answer to the essential questions cannot be given by official religions. The horizontal structure of the painting gives solemnity to the work not for the narrative but for the pictorial means with which Segantini painted the sky or the worn-out steps leading directly to the edge of the upper step. Segantini, who was far removed from Christian belief, although in his pictorial excursus he often referred to typical Christian religious devotion, said in reference to religion: “I never looked for a God outside of me because I was convinced that God was in us and that each of us is part of God as each atom is part of the universe”, referring to the universe as nature: mother and stepmother. This statement gives coherence to all his pictorial production.