This post is also available in:

If the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982 with a One Hundred Years of Solitude, has revived the interest in Latin American literature, Gonzalo Fuenmayor, fellow countryman, through his art halfway between magical realism and the McOndo style, has raised issues related to the exploitation of Latin American populations in Colombian history, and Latin America in general. With his works, he offers the ability to insinuate doubts with a form of surrealistic representation that pushes the viewer to observe the world with different eyes, to look beyond the appearance, most often banal, but behind which there is a more complex and harsh reality on which the viewer can focus more thanks to the use of charcoal.

Born in Colombia in 1977, he moved to the United States, graduating in 2000 at the School of Visual Arts in New York and subsequently attended the Master in Fine Art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 2004. During the years thanks to his brilliant university achievements, he won the prestigious Traveling Fellowship: a scholarship established in 1894 by James William Paige. This scholarship allows the few kids selected according to merits, to take a fully paid trip, in an area chosen by the student on the basis of their study plan to deepen the issues dealt with. The choice of Fuenmayor was Leticia, a Colombian city in the heart of Amazonia.

Besides being a renowned artist, Gonzalo Fuenmayor is an adjunct professor at the University of Miami (UM) where seen his talent, he teaches drawing at the School of Architecture, perspective and design at the faculty of Architecture.

Contradicting the common belief that Latin American art is a very colorful art, Gonzalo works almost exclusively in charcoal. The reason for this choice is the fact that according to the artist the vehemence of colors tends to divert the attention of the observer from the essential meaning of the work, that passes in the background. The colors push the observer to focus on elements that act as a corollary, while the use of charcoal in a game of black and white focuses attention on the meaning of the work by inviting the viewer to investigate its meaning.

For Gonzalo, black and white are indispensable to each other, complemented by enhancing the intensity of the work that comes out in all its beauty and three-dimensionality.

Gonzalo uses charcoal in all its forms, in different textures and shades: dust, pencils, chalk and sticks and its beginning dates back to the university days in New York, when its lightness and the low cost of the material allowed it to work anywhere and for a long time, refining the technique over time to create truly amazing architectural perspectives and studies, especially for the attention to detail. The white that derives from the use of charcoal is obtained either with the use of an eraser of different sizes and shapes depending on the desired effect, or by using the optical white of the sheet, applying a special film directly on the sheet that isolates the surface from charcoal which, being extremely volatile, would risk covering everything. In the purity of black and white the eyes and the mind of the observer investigate the work as it is, without frills or accessory fictions. It is interesting to understand the meaning of these two colors: if you asked a physicist what are the white and the black, he would probably answer that the white is the sum of all the colors while the black is the total absence; the same answer, given by an artist or a child would be the completely different.

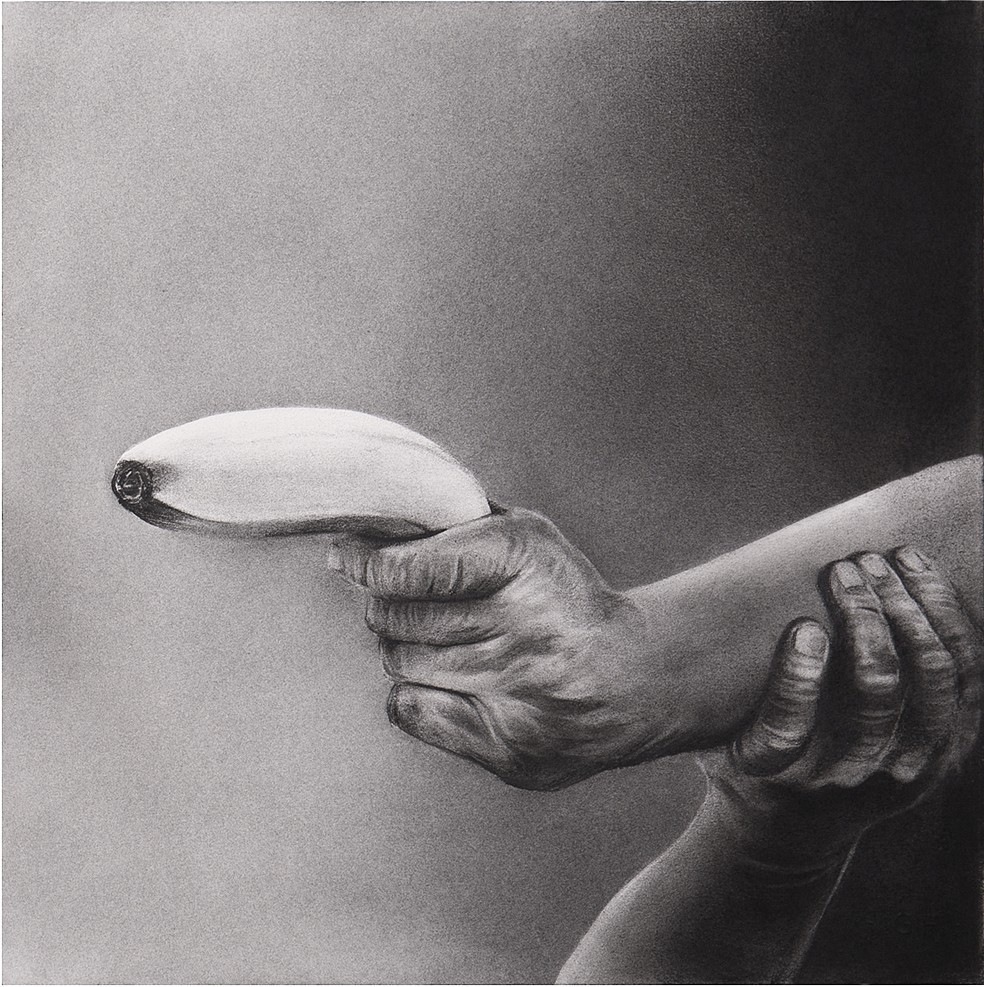

The themes treated by Gonzalo focus on the sense of immigration and belonging, and on the theme of opulence and decadence. Should we become American neglecting our culture, talking American, eating from Americans or must we remain tied to our traditions. Lawful questions that each immigrant asks himself every day and to whom it is sometimes difficult to find an answer. Gonzalo has decided to fill this gap between culture of origin and host culture through art, finding in the union of decadence and opulence the answer to many questions. He did so by taking as a symbol of his country of origin the banana which is the third largest agricultural export in the world.

The banana is a recurring fruit in his works, it is his Colombian heritage that lives within him and through which he wants to show people in the world facts they’re not familiar with: the years of Violencia, (1927) a tragic historical period that has led to the death of millions of people on behalf of the Colombian government, evoking scenes far from television fables propitiated by the media completely (or deliberately) unaware of what the fruit par excellence, eaten in every part of the world, hid.

Sometimes Gonzalo’s work starts from images found on the web, collages, etc… a source of inspiration in the development of the concept , and from photography and with which he then prepares drawings. What counts for Gonzalo is to be able to communicate a message through his works, and he does it in a refined manner with details and perspectives elaborated thanks to the studies done on site with installations designed by him.

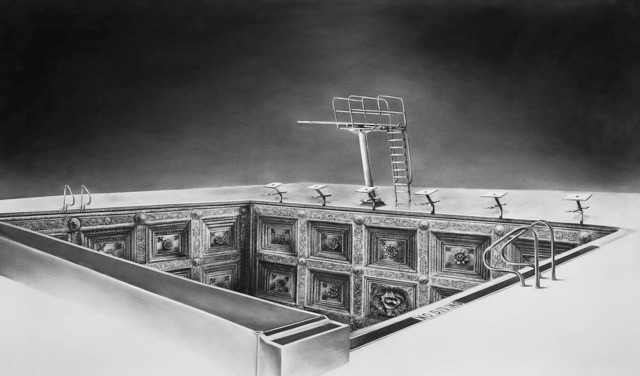

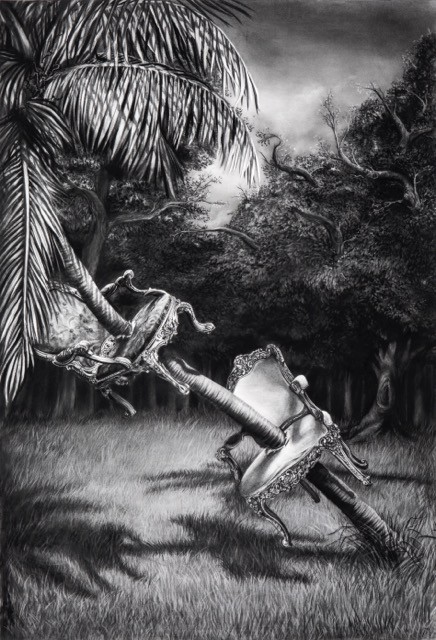

His works tend to highlight the relationship between opulence, so transient and fugitive and the moral decadence that derives from it, meant as an irreconcilable break between human beings and the world in general. Nature itself, a symbol of purity belonging to everyone but becoming in fact hegemony of the few who exploit populations with labor. In his works the bananas rather than the animals are represented in the form of cushions or carpets, mix glimpses of exotic landscapes left to be deduced by the presence of the palms and contextualized in urban environments: the fun and the transitory : the same image that Miami offers to the world. Among the works of Gonzalo often appears the surrealism of Magritte, in particular in Man in the Bowler Hat in which Gonzalo replaces the bowler with the Bolivian chola and instead of the bird, a swan, symbol of beauty and grace.

Moving away from his genre in the work The Flowers of Treason, still in the process of completion, Gonzalo succeeds, with a playful approach to reality, representing young and attractive guys and girls who do water skiing in company between smiles and fun, not caring that behind them the flames are burning their bodies. Their lives leaving them at the mercy of the transience of time.

The Happy Hour, instead, the work exhibited at the Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum, during the exhibition Deconstruction: A reordering of life, politics and art, was the biggest work composed by Gonzalo: 3 panels assembled together, 52 “x 20” each. A mammoth work that occupied the entire wall of the hall. The title is evocative of itself while the work is the decorations that are found on cocktails that are prepared every day for happy hour: fresh exotic fruit and umbrellas, very partyers that are then thrown away (caducity). Gonzalo represents them suspended, floating in the void. So unreachable and distant putting us face to face with our limited-time nature that seems to give us heaven but with a snap of fingers takes us back to the harsh reality, leaving us with this sense of fleetingness and ephemeral that is inherent in our human being.

.