This post is also available in:

The 23rd edition of The Art of The Portrait comes to life and does so with an exceptional artist: Max Ginsburg, 90 years old this year.

An innate talent that he experienced, when he was still a child, with his artist father.

In the series of works presented in his anthology there is the image of his parents, whom the artist immortalizes arm in arm: “the right one”, the artist points out, as they used to do in their shopping outings, as old people: “wonderful and sensitive people” Ginsburg says about them.

Ginsburg was able to bring together in his works, known especially for the representation of social scenes set in the Big Apple, the artistic technique and heartfelt participation in real events, without a trace of hypocrisy, having heavily lived, on his own skin, the years following the Great Depression and the wars.

In his career he has had many affinities with Norman Rockwell, the iconic artist known for his honest portrayal of everyday American life, with its rituals, its beliefs and its values, and of whom the artist claims to have loved not only his style but also his irony.

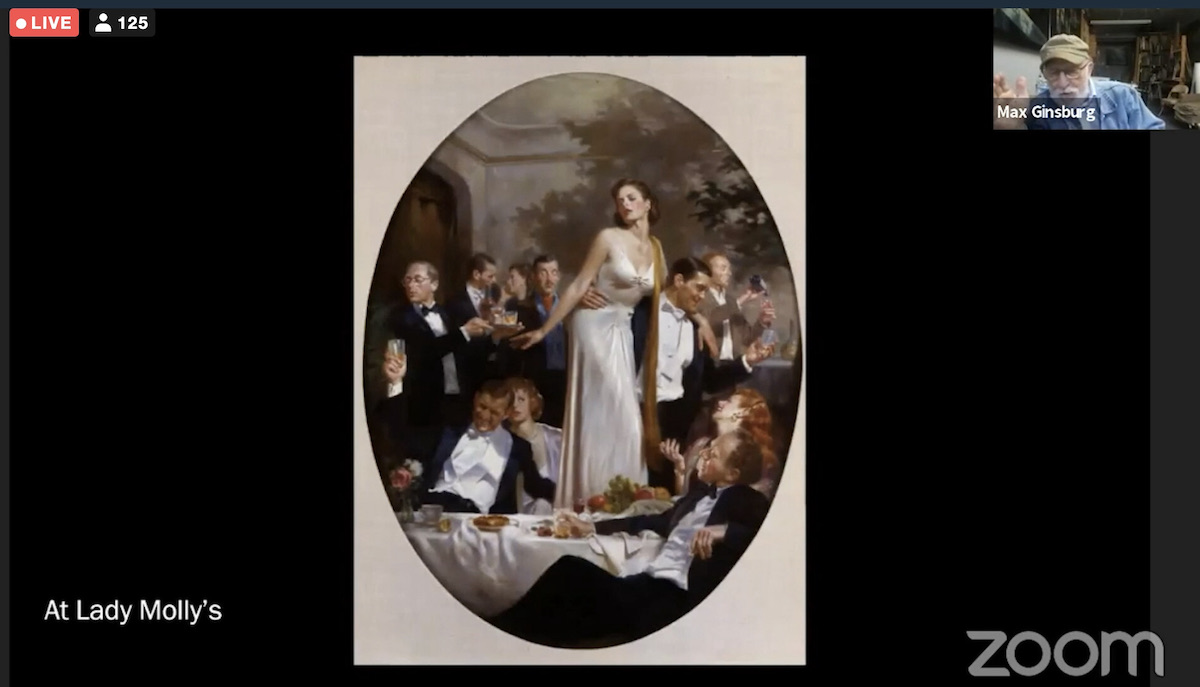

Like Rockwell, Ginsburg also devoted himself to illustration for many years: “I did it on the advice of a friend to scrape together some money because they were paying good money at the time”, Ginsburg states in all honesty. However, he later abandoned illustration to devote himself to painting, which characterizes him: ”brings to mind the figures of Tiepolo”, because of the multiplicity of people represented with a different perspective from each other, who tell the viewer of their reality made of facial expressions, gestures and design.

Looking at Ginsburg’s works, there emerge both walls, fences and barriers -which symbolically undermine the meaning of individual and collective freedom- and images of his wife and himself -as Norman Rockwell often did- and which in Ginsburg’s case represent their participation in real events as participants in “social revolt.”

Ginsburg’s process of artistic composition begins with the definition of large masses, and ends with the individual study of models who are mostly students, acquaintances and friends, whom he represents and of whom Greeny and Ricky Muijca-are examples. It is not unusual for the artist to have the same people pose in different positions in the same composition.

To these people -along with the technical skill due to experience- he attributes characteristics of his own because: “I use photography to capture reality which I then transform into fantasy on my canvases”, says the artist.

In Ginsburg’s works, when he works with photography, the backgrounds are often elaborated later, stealing a few more excerpts of the city. Max Ginsburg says he is pleased to be considered the people’s painter.

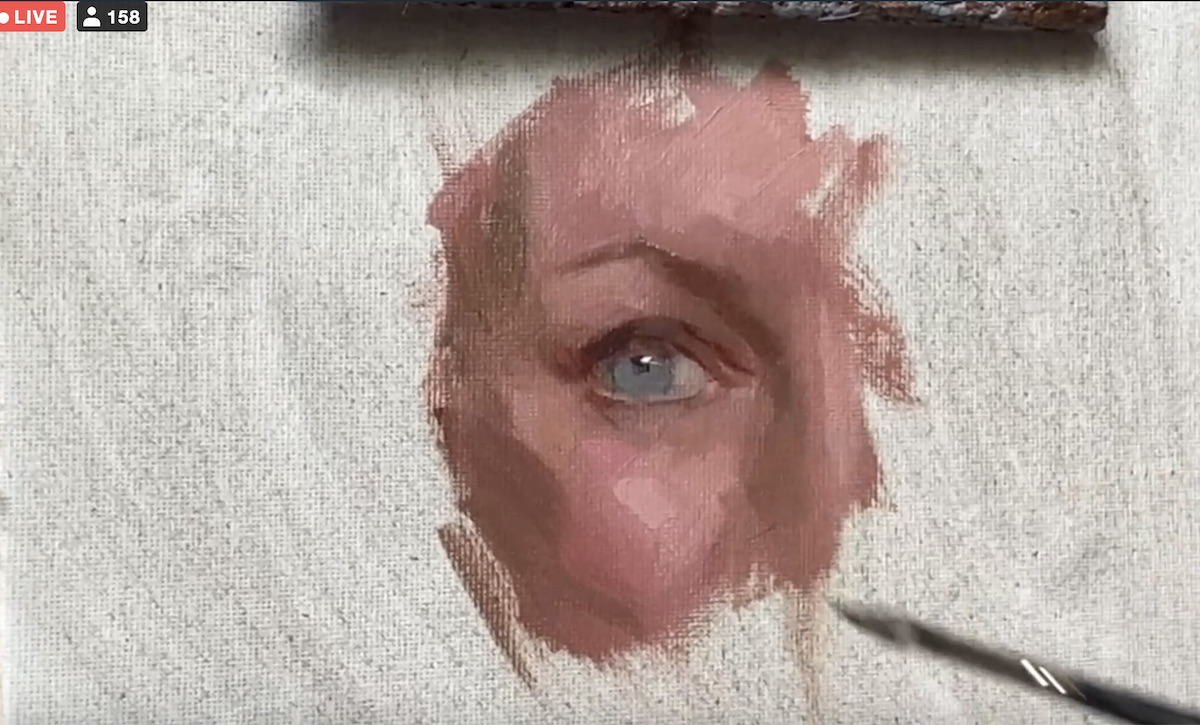

Michael Shane Neal resumed the role of cicerone today, accompanied by artist and lifelong friend Dawn Whitelaw with whom he focused the attention of participants on the importance of edges and how their study brings the quality of the work to a higher level. In addition to the theoretical section realized through the analysis of some masterpieces of the history of figurative art, the speakers performed, both, a live demonstration, in which they showed in a practical way how the edges can be realized in many ways: starting from the use of a particular type of canvas and brush, to the creation of halftone with the creation of an intermediate tone.

Edges can offer a brilliant illusion of reality and its interpretation, a fundamental component for art because making art is to delve into the construction of edges, focusing on what you want to highlight. “Corner harmony only comes from observing and practicing,” says Michael Shane Neal while Dawn Whitelaw suggests “thinking exclusively in three tones: soft medium and hard, to see how they interact.”

A demo defined, “A real gourmet meal with two masterchefs!”, says one participant.

Joseph Q.Daily’s afternoon workshop clearly and immediately provided concepts that may be easy to assimilate on a theoretical level but are less immediate on a practical level.

Starting from the importance of three-dimensionality, in drawing as in painting, it opens a door to the wonderful world of perception of the viewer to whom the artist has the task of conveying emotions and feelings. “You can’t teach how to create with love and gratitude, but you can offer practical advice that can help the artist better understand the importance of three-dimensionality through three key concepts: value, form and depth of space.”

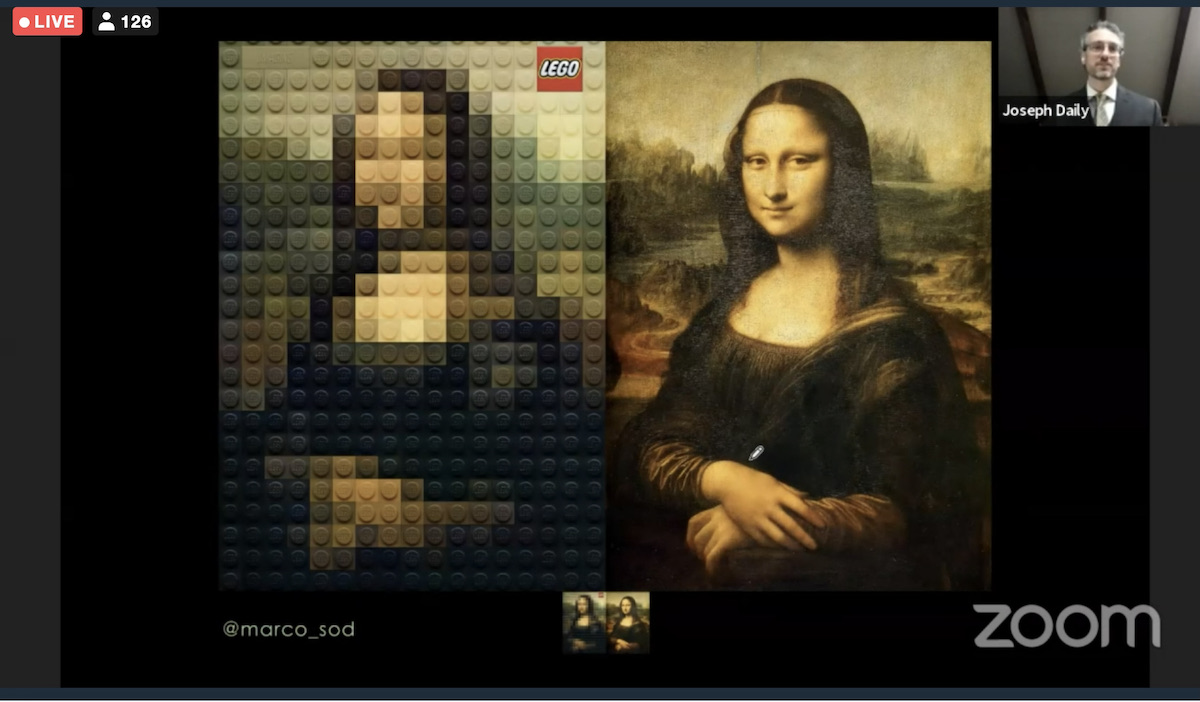

Mentioning a quote by Sargent in which he remembers the importance of thinking of a face as if it were an apple, Daily proposes a very simple image of a mosaic construction made with virtual Lego bricks -by artist Marco Sodano, (@marco_sod)- with which he introduces fundamental concepts in art that include edges and perspective.

Concepts that focus on the importance of seeking the simplicity of geometric shapes in reality, learning to distinguish increasingly complex contexts. This will lead to the not-always-obvious conclusion that soft edges are lighter the farther they are from the surface on which the shadow is cast, just as closer objects will be more in the light than more distant ones.

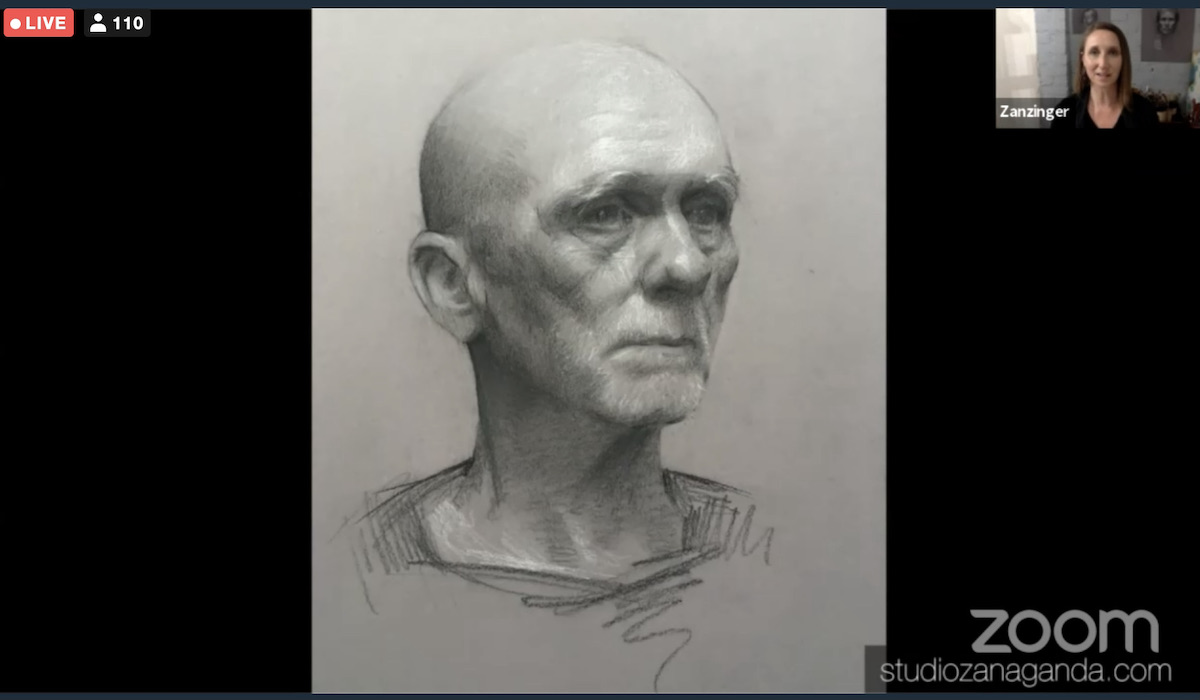

It is a hands-on demonstration by Elizabeth Zanzinger that closes the day of the convention.

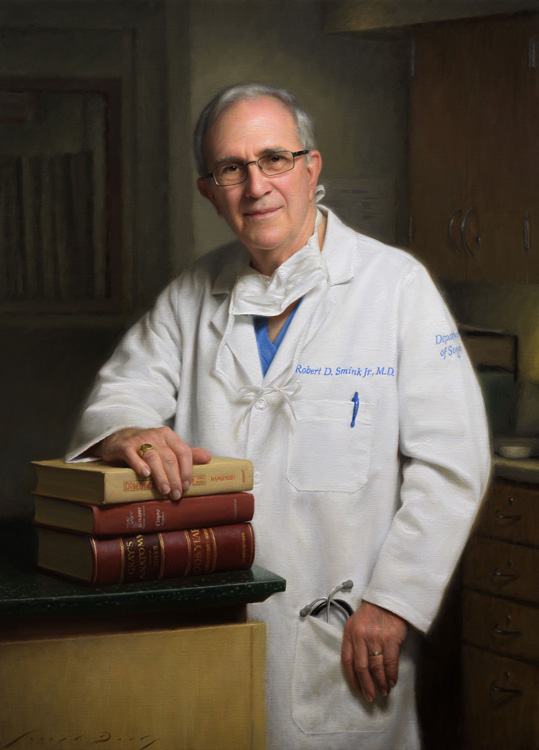

The artist’s approach to portraiture is a condensation of many methods learned during her years of study, first at the Gage Academy of Art in Seattle, Washington, and then at the Grand Central Academy in New York. Zanzinger mentions the methods and teaching supplements provided over time by: Andrew Loomish, George Bridgman, John H. Vanderpoel, and Charles Bargue, she creates a live portrait from an amalgamation of the above methods that she uses at the appropriate time. Her work process consists in the representation of shapes that from large progressively small, leading the artist to refine the work in the detail that finds its completion in the composition of eyebrows, beard and mustache.

Zanzinger is a supporter of triangulation, i.e. the technique of calculating distances between points by exploiting the properties of triangles, so as not to fall into an error of proportion and instead offering the possibility of building a solid anatomical structure. And her final work speaks for itself. “Drawing develops observation and empathy, and it’s a privilege to be able to observe the world through the eyes of an artist,” says Zanzinger, who highly recommends a sculptural drawing class to delve into the three-dimensionality of the human face.

A very busy day with a varied educational program that will continue tomorrow with other distinguished guests who will dispense advice showing us their mental and physical processes.

(On the title: Tire Swing, 2003. by Max Ginsburg. Oil on canvas, 36 x 36”)