This post is also available in:

The MOCA -Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami- in conjunction with Miami Art Week has set up the exhibition, retrospective: “My name is Maryan”, on display until March 20, 2022. Maryan S. Maryan is the stage name that artist Pinkas Bursztyn -from his mother’s maiden name- adopted as an act of radical self-definition after his liberation from the Nazis, who left him as the sole survivor of his family.

The retrospective exhibits the works of this poignant and innovative artist, who during his short but prolific life – he died of a heart attack at only fifty years of age – was among the first artist- witnesses to directly represent the dramatic experience of the Shoah, while refusing the label of “Holocaust artist”. Maryan offered, with his life and through his works, a reason for hope: despite witnessing cruelty, oppression and exploitation, he was a resilient and courageous artist.

The exhibition through this retrospective reaffirms the importance of the 1948 “Universal Declaration of Human Rights” at the turn of World War II, which states that: “Human rights don’t exist in the eye on beholder. They are based not on the whims of any particular governement but upon the recognition that all humans everywhere have equal ianlenable rights, that everyone as a memeber of the human family deserved to be treated with dignity.”

Born in 1927 to a traditional, working-class Jewish family, Pinkas and his family were captured in 1939 by the Nazis. From there began his journey to hell remaining the only survivor of the family. He was imprisoned in various forced labor camps and then ended up in the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau. Despite having undergone the amputation of a leg, the artist found himself more than once face to face with death which however spared him allowing him to live a life that as the artist defined: “is no longer life”.

With the end of the war, in 1947, he emigrated to what was then Palestine to begin his artistic training, first in Jerusalem and then at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where he exhibited in important galleries, forging a distinct independent style but adjacent to the École de Paris and the CoBrA group.

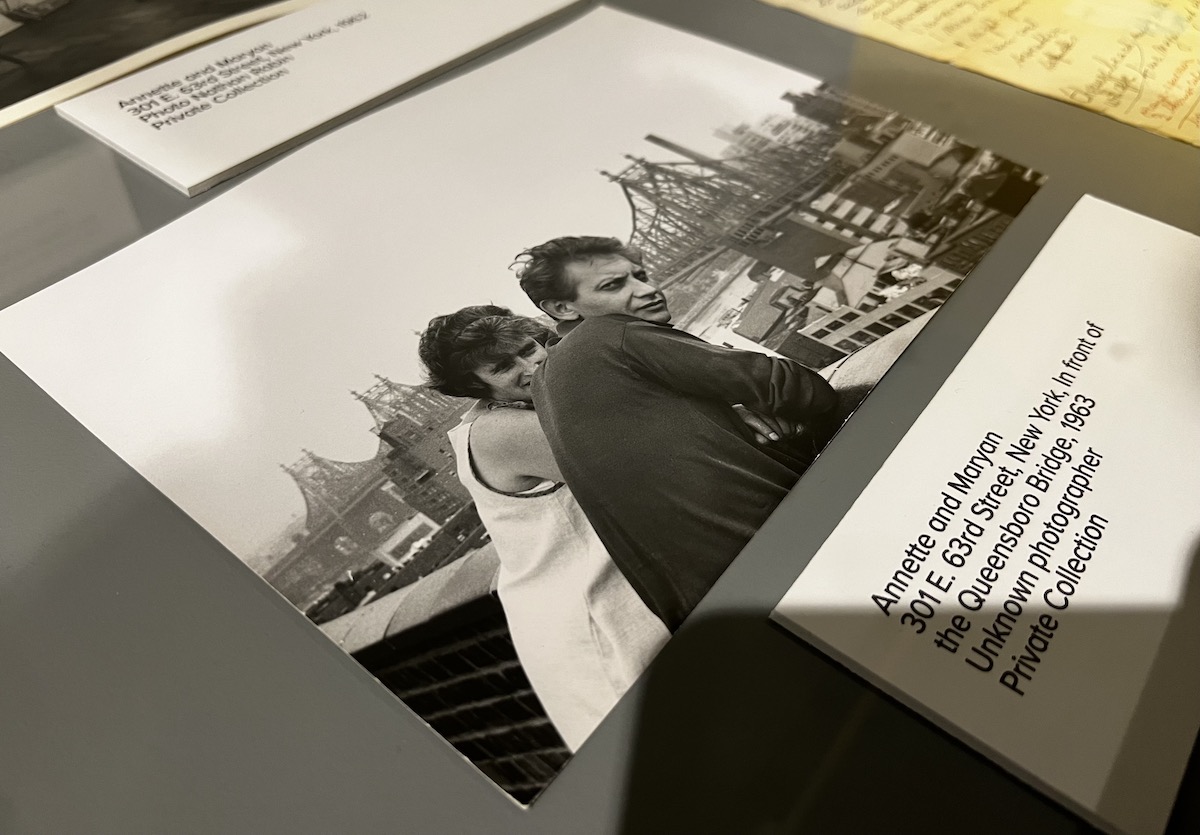

In the ’60s he emigrated to New York, in the famous Chelsea Hotel, where he developed the concept of “personnage”: both historical and fictitious figures -which become in mature age, the subject of his works- used to explore psychosexual tropes and characterized by color combinations so strong as to be tragic. The “personnages” are rich in symbols, legible as the Star of David and pointed hoods that echo the Spanish Inquisition and the Ku Klux Klan, as well as rich in esoteric and personal references. The characters are almost always located in claustrophobic spatial environments, such as boxes. The latter will also be represented in later years, in his notebooks, as a direct reference to his experience in the Nazi camps.

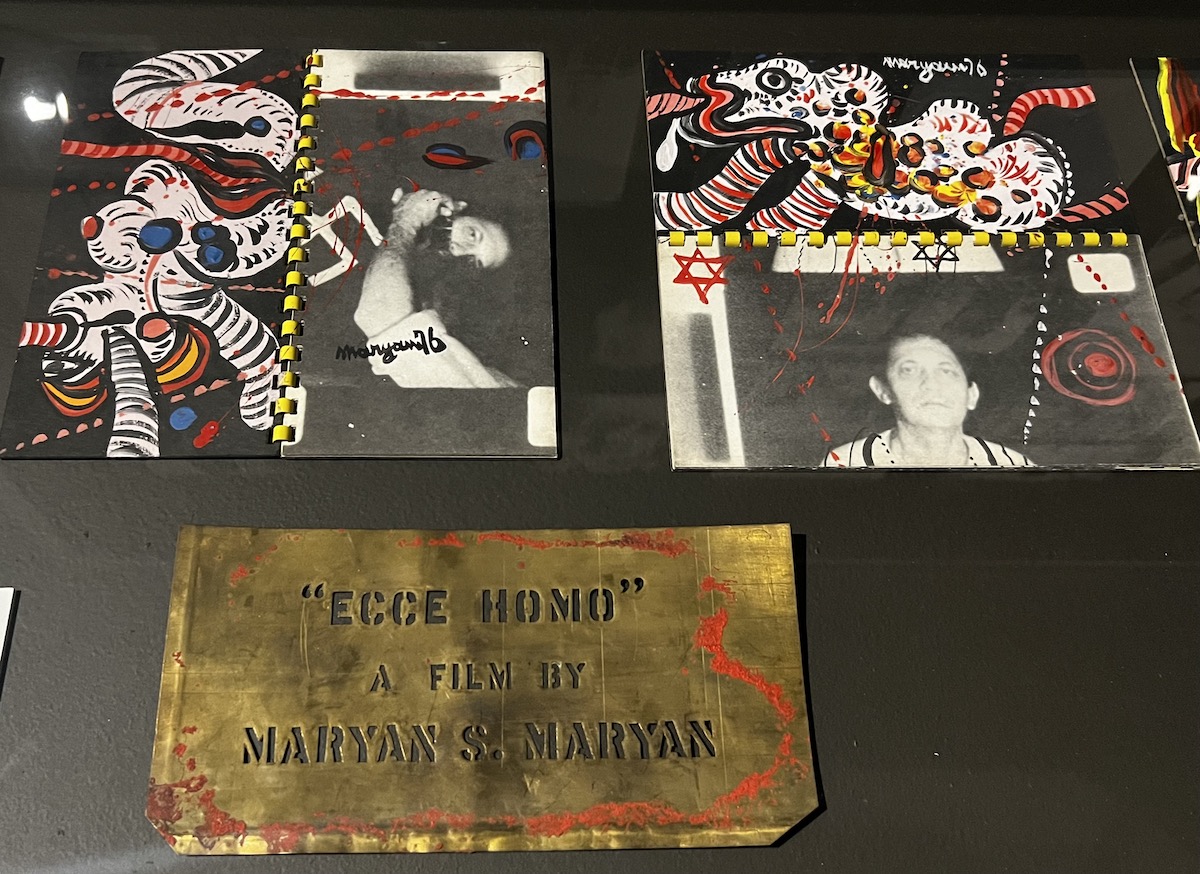

The last decade of Maryan S. Maryan’s life was as emotionally and physically turbulent as it was extremely prolific. Post-traumatic illness and the psychological fallout from his experiences as a young boy overwhelmed him in the early 1970s. It was then that, under the care of a psychiatrist, he filled notebook after notebook with drawings and texts that provide insights into his biography and the recurring motifs of his art. Drawings that are displayed digitally and in rotation at MOCA, along with memorabilia from the film in which the artist gives a firsthand account of his experiences in Nazi prison camps with images from other social protest movements.

The retrospective features all the works that characterize his life stages. The exhibition opens with the only self-portrait produced by the artist when he was a student at the École de Beaux-Arts in Paris. The work, which recalls the elongated necks of Modigliani and the style of Chaïm Sautine, represents in appearance a calm and serene young man. Analyzing the work, it is possible to see one of the bullets received by the Nazis under his left eye.

The reconstruction of the room of New York’s Chelsea Hotel, brings the viewer to relive in an immersive way the environments frequented by the artist. New York’s Chelsea Hotel, also known as the “Ellis Island of the avant-garde,” was a bohemian enclave used as a home-studio for artists such as Jackson Pollock, Tennessee Williams, and Niki de Saint Phalle, and it was the nerve center for art.

Among the works on display in the room at the New York Chelsea Hotel are, in addition to some objects Maryan has collected, some works pertaining to the crucifixion, round paintings and a rare polyptych. In the cruciform paintings that exalt the theme of victimhood and sacrifice Maryan often referred to the human suffering of Jesus Christ, depicting singular figures in exaggerated states of anguish and suffering. The round paintings, on the other hand, refer to the “Wawel heads”, works produced in the workshop of Gothic sculptors Sebastian Auerbach and Hans Snycerz around 1540 and installed on the coffered ceiling of Wawel Castle. The heads made by Maryan are typical of his style. In the room there are also many masks of African, Oceanic and Mexican origin, which represent for the artist a clear departure from the Western conventions of realism in favor of abstraction. They are the inspirational rejoinder to the canon of Western artistic tradition, which for centuries has favored realistic portraiture and idealized beauty derived from ancient Greco-Roman standards in favor of faces that have provided another way of imagining the expressiveness of the human face.

Maryan often worked in series, exploring variations of the same theme. His wife Annette wrote about his studio habits that: “painting was his liberation and once he started working on a canvas, he usually tried to finish it the same day.” In this series the artist evokes a number of art historical antecedents that influenced his development, from Goya to George Grosz and Max Beckmann to Fernand Léger. In this series he depicts some of the characters that would also appear in his works over the following decades: the male figure with donkey ears, a tortured figure with his legs in the air, and figures with strange pointed hats.

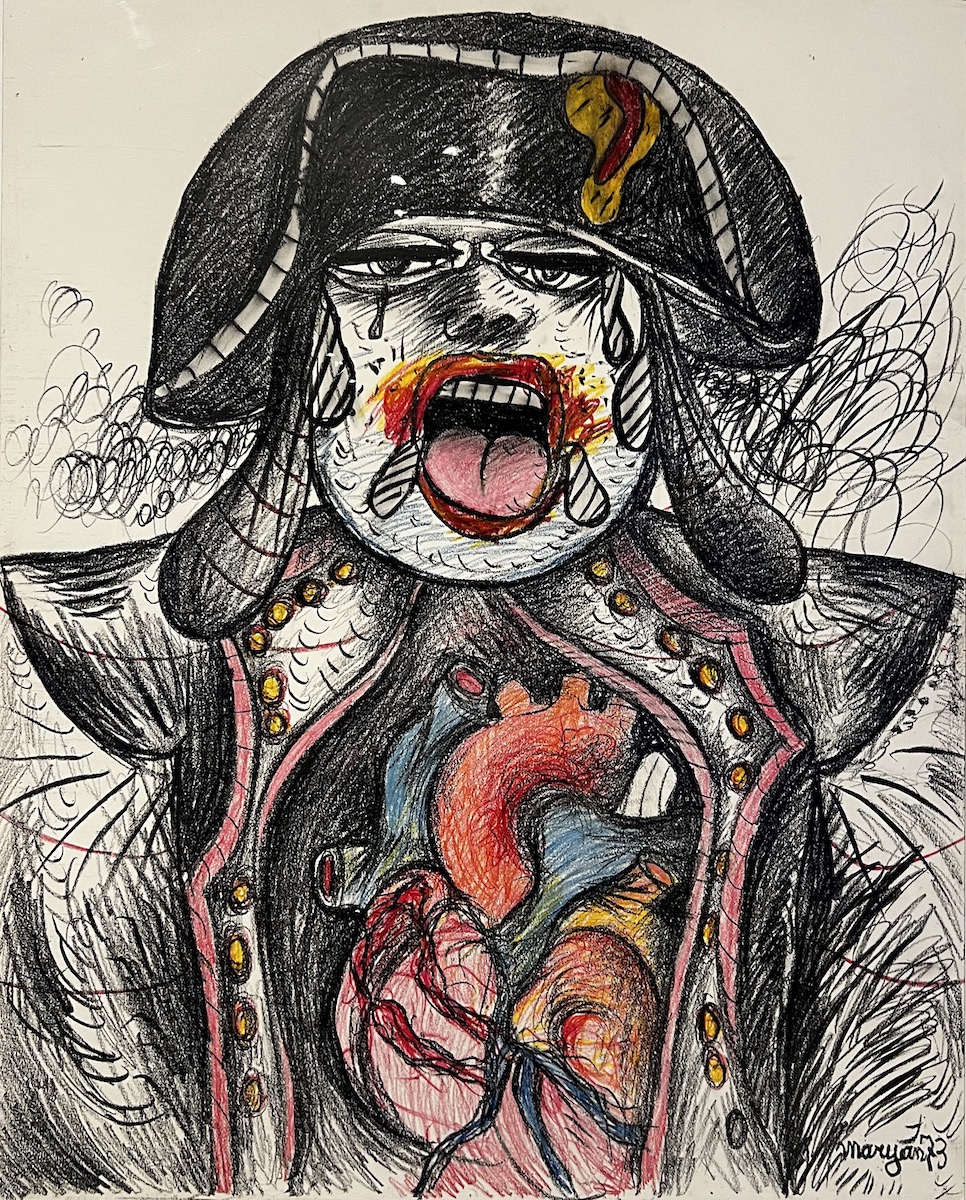

The artist’s vigorous and liberating rhythm is evident in his series of Napoleon drawings done in pastel in 1973-74, in which Maryan transforms the French leader Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) into a grotesque caricature of human absurdity and cruelty. While the military regalia and the distinctive bicorn hat are elements that remain unchanged in the Napoleon series, the character is instead shown in various states of distress – sweating, vomiting, with his head matted. The choice of Napoleon as the subject seems related to Maryan’s complicated relationship with military France and the French government’s denial of citizenship.

Maryan was a voracious and astute student of the old masters who came before him and who were true inspirational muses for him, to whom he refers several times in the series, “After….” Among the artists who have most fascinated him are: Velazquez, Hals, Rembrandt, Vermeer and especially Goya, who with his work, “The Tribunal of the Inquisition,” depicts the barbarity and public torture of Jewish “heretics” by the Spanish Catholic clergy.

The exuberant art scene of the New York Chelsea Hotel is also experienced first in Paris during his years of study at the Ècole National Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in 1950, where although he never aligned himself with any particular artistic group, he had the opportunity to meet emblematic and established figures, symbols of post-war art, among them: Pablo Picasso, Jean Dubuffet, Alberto Giacometti, his former teacher Fernand Léger and Jean Atlan. The latter, a French-Algerian artist and poet, in particular, was one of the leading exponents of the CoBrA collective -a name derived from the contraction of Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam- which particularly fascinated Maryan. The CoBrA group, in abolishing the divisions between figurative and abstract art, was politically opposed to Nazism and favored experimental art practices: non-Western art, the works of children and psychiatric patients, creating a unique vision of modernism. In MOCA’s gallery, Maryan’s key early works are juxtaposed with an emblematic selection of works by CoBrA artists from the NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, specialized in CoBrA works.

Maryan’s most prolific period was in New York from the 1960s until his death. In the American city he began exhibiting at the Allan Frumkin Gallery, forging friendships with famous artists such as H.C.Westermann and June Leaf, Leon Golub and the “Monster Roster”, mid-century Chicago artists. Maryan’s American period includes several distinct bodies of work that expand on his character paradigm related to psychosexual themes in which phallic snake-like forms with human figures emerge. By the late 1960s, Maryan’s characters become more abstract and frenetic. They are often painted on solid backgrounds with bright colors that contrast with the humanoid forms, many of which are reduced to just hands and mouths.

Maryan’s Jewish-Christian identification is explicitly explored in the film, made in 1975 in collaboration with his friend and colleague Kenny Schneider entitled: “Ecce Homo”, which represents the culmination of the elaboration of his experiences, as an attempt to create an equivalence between the Holocaust and the socio-political struggles of the time. The film, which takes its name from the Latin phrase frequently used in Christian art, is a tragic and moving account done, in the first person by Maryan, with still images of contemporary historical events and images from the era of controversial political subjects. The performance is a cry of pain and mercy for a life anything but easy in which the idea of killing a German turns out to be a good solution only on a mental level because in fact the artist, declaring himself incapable of killing a human being, shoots instead with bayonets at dummies representing Nazi officials.

My name is Maryan insert this complex ouevre into a large narrative of postwar European and American Art history in which he forges a defiant yet questioning form of humanism that himself defined “truth painting.”

.