This post is also available in:

The last day of the 24th edition of The Art of The Portrait began with the “Inspirational Hour”, with the testimony of Leslie Adams, an award-winning artist whose mission, as stated by the artist: “Inspire people to dream”.

Making an excursus on her most significant works, Adams stressed that her childhood, spent within the walls of the Toledo Museum of Art, in Ohio, in the company of thousands of works of different periods and manuscripts, had a fundamental importance in her artistic development because they gave her the possibility to dream. A component, the dream, that the artist carried with her for the rest of her life and is symbolically represented in each of her works. “When I was a little girl, I dreamed of being able to work for Walt Disney because I was constantly drawing Wonky and his world,” says the artist whose skills, especially in drawing and calligraphy allowed her to win the Grand Prize at the International Collegiate Figurative Drawing Competition. With this award, sponsored by Andy Warhol, Adams received a full scholarship, to the prestigious New York Academy of Art. From graduation to commissioning a dozen official portraits for the State of Ohio, the step was short, and her passionately cultivated dream of becoming an artist led her to win the Portrait Society of America’s prestigious “William F. Draper Grand Prize”: the highest honor bestowed by the institution, and the first to be won for drawing.

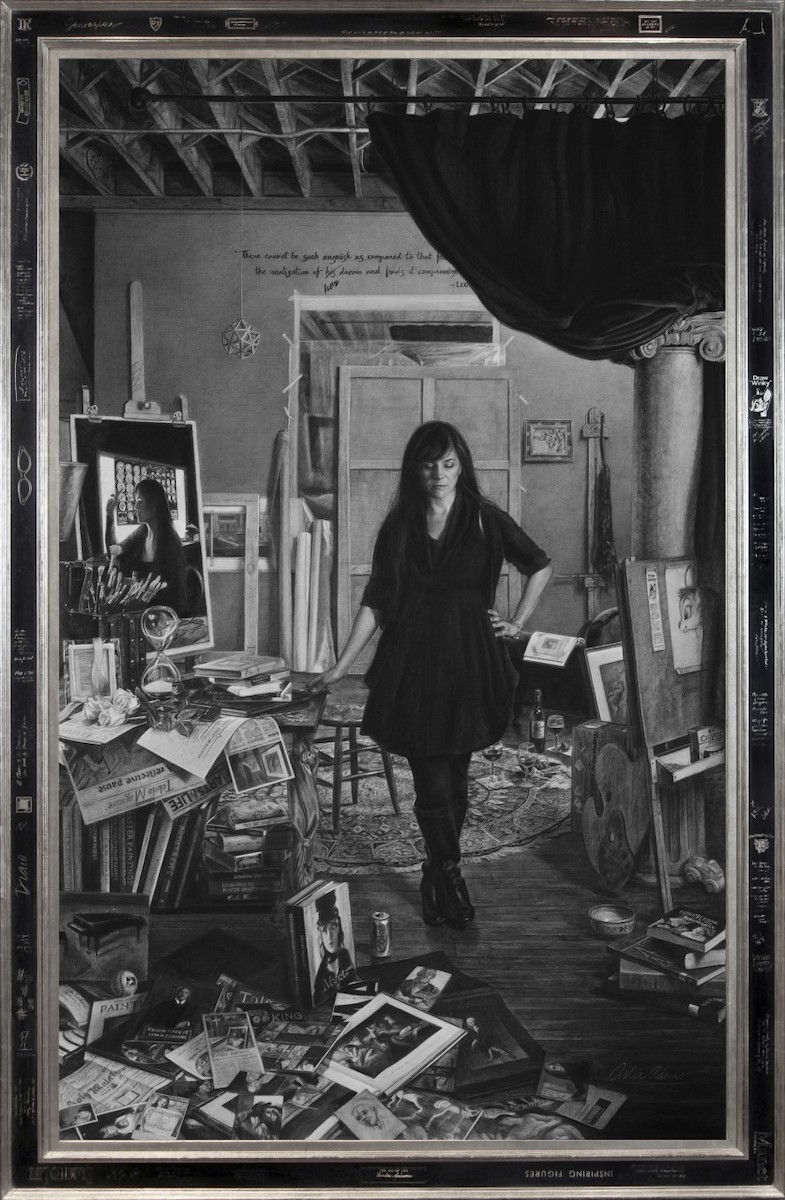

While facing numerous professional challenges that have encouraged her to try her hand at difficult undertakings, such as deciding to radically change medium and compositional style, Adams has always dreamed big, even managing to receive commissions from personalities of the religious world – an example is “The Most Reverend Leonard P. Balir, Archbishop of Hartford”, a work exhibited in the Cathedral of Saint Joseph in Hartford, CT. Thinking about the sacredness of works displayed in churches or other religious settings, painting these kinds of commissions has always been such a great ambition for Adams that it even seemed unattainable. “I’ve always been incentivized to dream, that’s helped me achieve my goals, and I want people, especially children, to be able to do that,” the artist said. This concept is figuratively represented in the project “Handwritten Dreams” and even more so in the work Sensation. Handwritten Dreams was born on the basis of the cataloging of dreams that the artist has always done over time, writing them on small cards distinguished by category. The series consists of charcoal portraits in which she, a schoolgirl, writes on the blackboard, thus emphasizing the element of drawing and calligraphy. In the work “Sensation”, on the other hand, the adult Adams represents herself in a room full of past and present objects with a strong symbolic value – books, magazines, the certificate of merit, paintings, the wedding picture of her parents twenty-five years later: everything that in life has made her laugh and cry, once again highlighting the extension of the dream in time, between past and present, between what is desired and what is realized.

Victoria Wyeth, Andrew Wyeth’s only granddaughter, already the protagonist last night of: “Andrew Wyeth: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” with which she showed self-portraits of her grandfather-some of them previously unpublished-and his artistic evolution from oil to watercolor to egg tempera. With the presentation of Andrew Wyeth: Close Friends” she focused instead on the social sphere of her grandfather and of those characters that for sixty years he constantly, almost obsessively, represented. What emerges is the image of a cultured and refined artist who has stated, ” If you think you know my work, turn the painting inside out: you’ll find that I’m not a realist painter but an abstract one.”

Victoria Wyeth’s picture of her grandfather, in a manner that is both lighthearted and emotional, is that of an exceptional artist who loved people more than they loved him. In his works, in which the care of the background is almost more important than the subject represented, appear the characters of the most intimate sphere, family members, but also neighbors and people accidentally happened in his life and linked to him by a double knot thread. An example of this is the subject represented in The Drifter (1964): a painter who happened to be there by chance and who attended Wyeth’s studio for ten consecutive years just to be able to watch him paint. Victoria Wyeth, in a light-hearted and emotional way at the same time, highlighted her grandfather’s particular character and his unique and inimitable way of seeing life.

It was artist Quang-Ho, who introduced Daniel Sprick, “the silent artist” who officially closed the conference with a session on “Reality and Perception”. Defined the “artist of atmospheres” for the incredible ability he has to project the viewer into the suggestive atmospheres of his paintings, Daniel Sprick led a lecture in his brilliant and sober style, ironic and shy at the same time. Talking about the misperception of reality due to the preconceptions that inhabit the collective memory, the artist has reviewed works by artists of the past, which have influenced him in some way, alternating them with the works he has created over time. According to Sprick, visiting museums is an extraordinary way to enter the stream of consciousness of past artists who always induce reflection in the artist’s critical eye.

Sprick says that his compositional process always starts from a general idea that he refines in the course of work and in which he sometimes inserts – a posteriori – accessory elements or in which he recreates fictitious atmospheres with sources of light, non-existent in the physical space, but perfectly logical in his mind and in the pictorial rendering. The theme of death is a recurring theme in his production and is addressed both explicitly, in the representation of parents in the last moments of life -a means to exorcise fear and pain- and through the presence of physical skeletons that inhabit his compositions and in which, the psychological and compositional “sin”, can be equivalent or have the better of each other thanks to the exaggerated rendering of value contrasts. The sensitivity of the artist sometimes obliges him to leave in suspense his compositions that he resumes after years because he is not perfectly satisfied and about which he says: “Our work is never exactly what we want but at a certain point we have to forgive ourselves and go beyond”.

Michael Shane Neal, chairman of the board of the Portrait Society of America, marked the closing of the XXIV edition of The Art of The Portrait. Among the greetings and thanks Mr. Shane Neal officially declared that the XXV edition of the annual conference will be held in Washington D.C., May 11-14, 2023.

Registrations are already open, you just have to register to enjoy magical moments in the company of extraordinary artists.