This post is also available in:

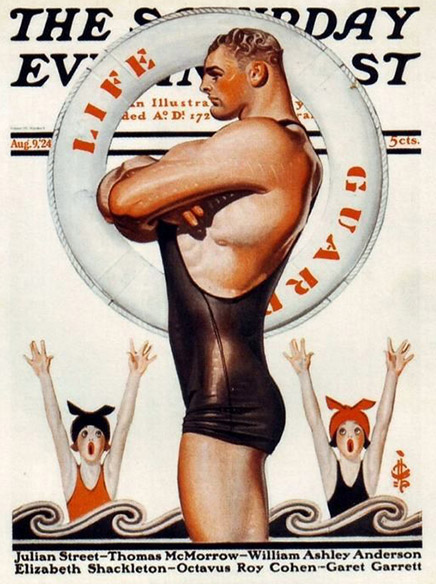

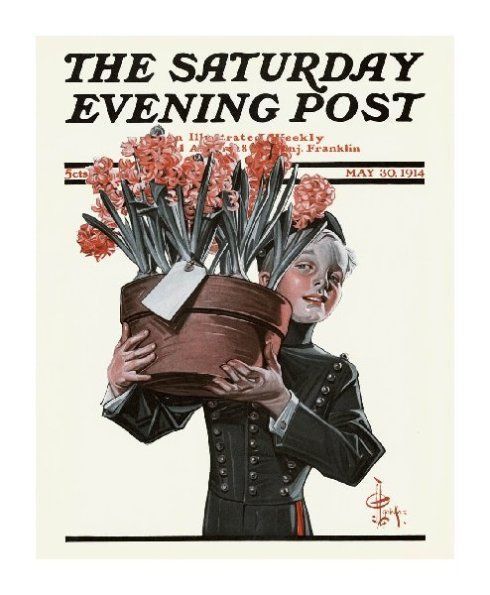

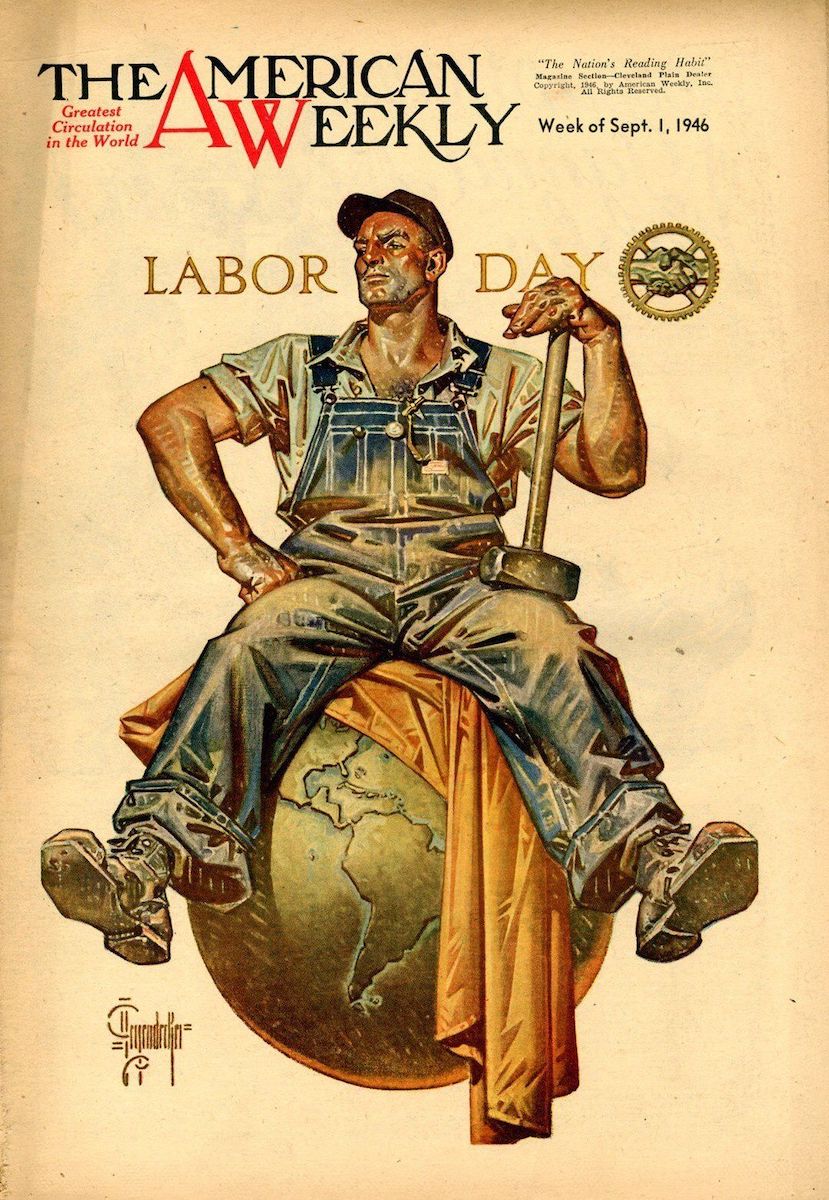

Joseph Christian Leyendecker was one of the greatest illustrators of “The Golden Age of American Illustration”: the period between 1850 and 1925 during which American illustration art had reached its peak. Although J.C. Leyendecker was almost forgotten, after the covers of Norman Rockwell who, with his iconic images of America linked to the values of the God, country and family, made both Americans and the rest of the world dream, Leyendecker produced only for the Saturday Evening Post 323 covers – in addition to other advertising illustrations for the inside pages – with a collaboration with the magazine that lasted for 44 years.

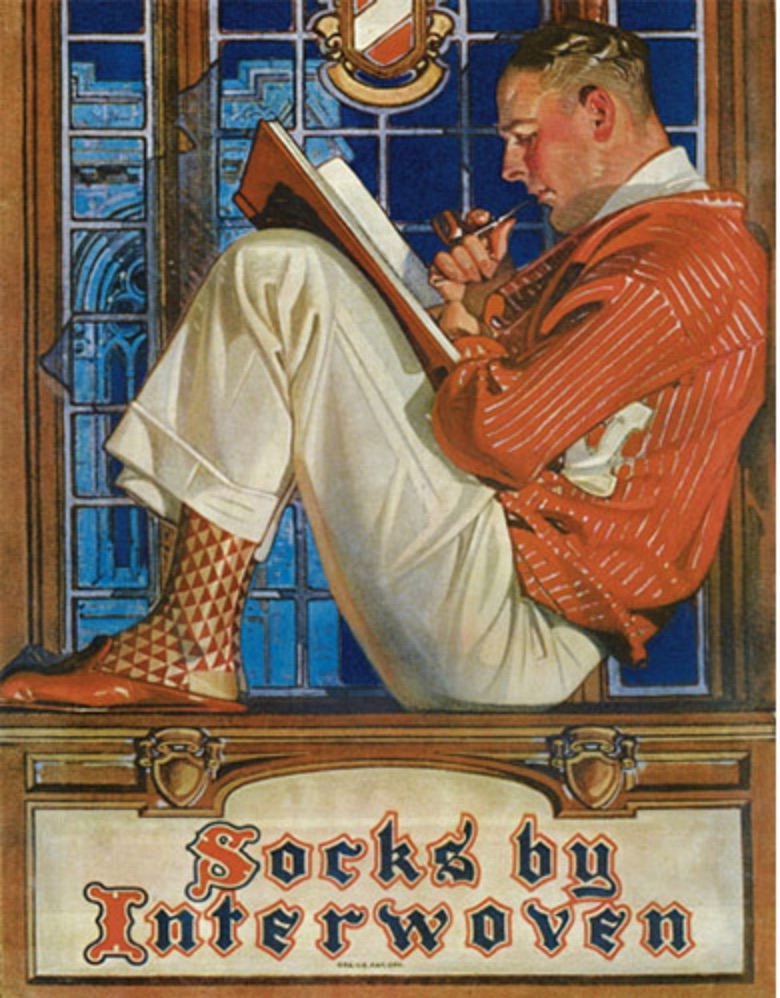

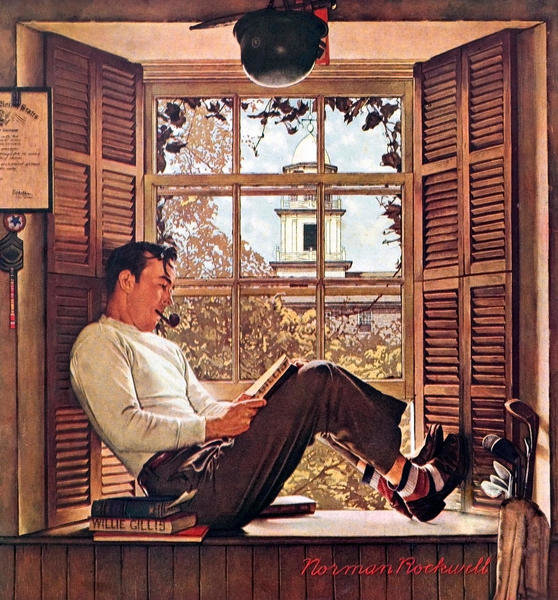

After all, Norman Rockwell, born two decades after Leyendecker, when he started his career as an illustrator, took him as example: the proof is the representation of “Interwoven Socks” by J.C.Leyendecker, 1921 and “Willie Gillie in College” by Norman Rockwell, 1946.

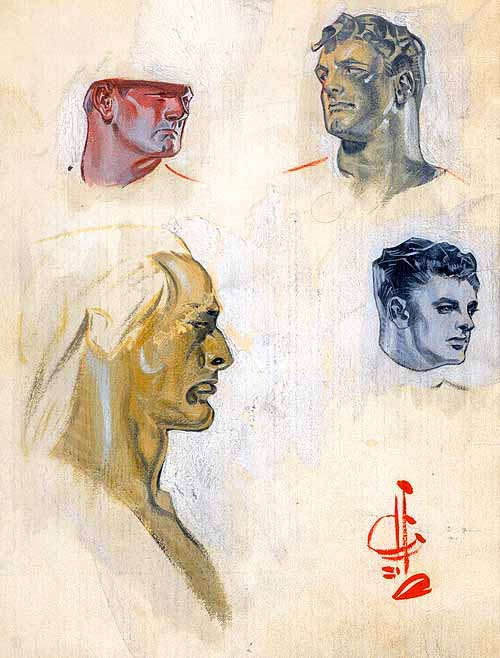

His approach to the art of illustration was characterized by a very broad stroke, deliberately executed with control and with the distinct cross-hatching style that characterized some of his works, that were rarely overpainted. After all, he was an artist: he had a live model in his studio, on which he adjusted the light and which he then represented on canvas. Canvas that was then reproduced for publications.

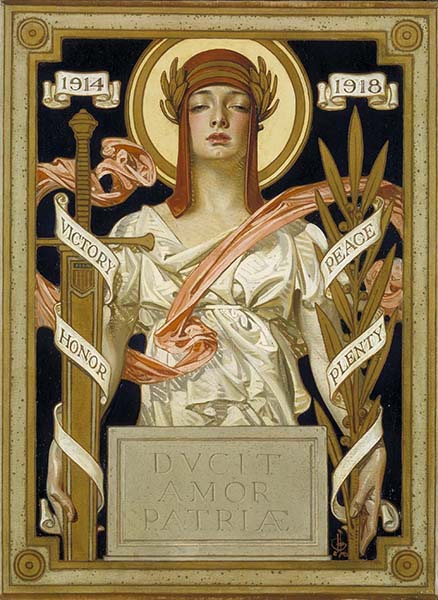

J. C. Leyendecker was born in Germany in 1874, in Montabaur, a tiny village not far from Reno, and emigrated to America, in Chicago, IL, with his family in 1882. After studying drawing and anatomy with the illustrious John H. Vanderpoel at the Chicago Art Institute (John H. Vanderpoel is an artist who still studies today in academic-style atelier) J.C. and his younger brother Frank enrolled at the Académie Julian in Paris, which they attended for a whole year and where they got to know the art of Alphonse Mucha, who inspired J.C. in some of his works.

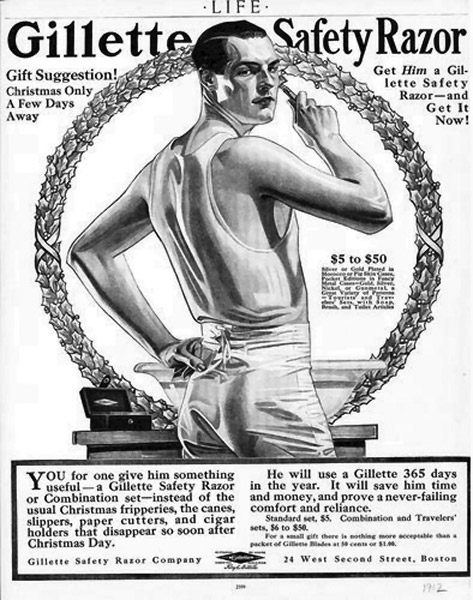

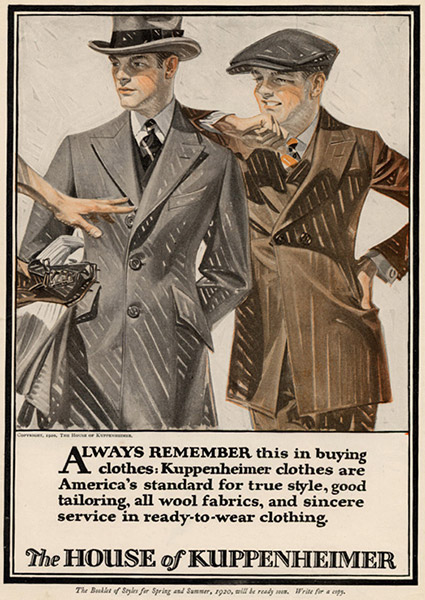

In 1900, Joe, Frank and their sister Mary moved to New York City where they began long-term, lucrative business relationships with a number of clothing manufacturers among them: Arrow Collar Man (the manufacturers of the famous detachable collars), Interwoven Socks, Hartmarx, B. Kuppenheimer & Co. Cluett Peabody & Company, but not only that, he also worked for Gilette, Karo Syrup, Maxwell’s Coffee, Kellog’s and Chesterfield cigarettes. With his images he defined the figure of the American macho male and fashionable during the first decades of the twentieth century. For his figures he used almost exclusively his model, who was also his partner for 50 years: Charles Beach, who moved with him, Frank and Mary, to the mansion -and art studio- purchased in La Rochelle, New York, where he remained until the end of his days. Accustomed to a luxurious life of parties in which the creme de la creme participated, it seems he was a source of inspiration for the novel The Great Gatsby.

J.C. Leyendecker virtually invented the whole idea of modern magazine design: he literally broke with the rectangular format and the lettering, which used to be on the top, was replaced by circular characters that he borrowed from Japanese design. No other artist, except Norman Rockwell two decades later, has been so firmly identified with the idea of art in the publication.

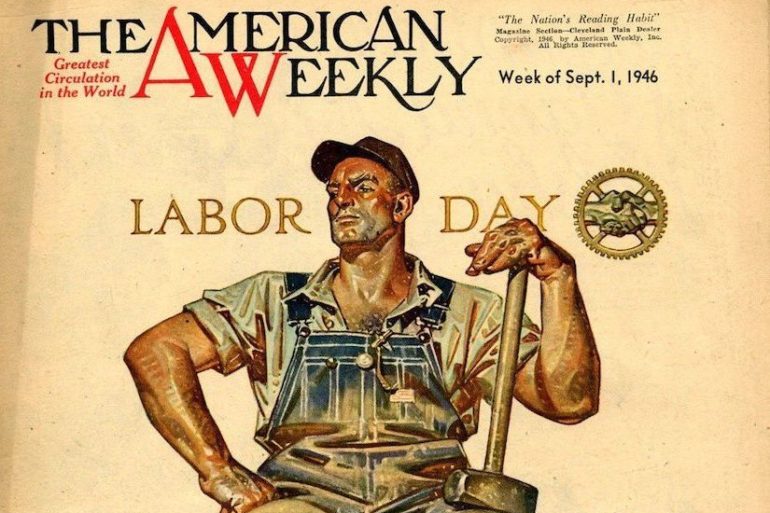

Among his memorable creations, in addition to the advertising images related to collars and fashion, the collaboration with the Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, there are the first covers dedicated to Mother’s Day created for the Post that kicked off the flower delivery industry for the occasion, just as he invented the American tradition of the fireworks blast on July 4th, American Independence Day. Between 1896 and 1950, Leyendecker painted more than 400 magazine covers and 60 biblical illustrations for the Powers Brothers Company.

The 1920s were in many ways the pinnacle of Leyendecker’s career and he also painted recruitment posters for the U.S. military and the war effort. Unfortunately, the collapse of Wall Street in 1929 did not spare him either, as he saw the number of commissions drop dramatically to the point where he had to fire all the servants at home in order to maintain it. He died of a heart attack in 1951 and his grave resides in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, along with the rest of his family.

.