This post is also available in:

Louis Hippolite Bayard was the first photographer to talk about a photographic exhibition in Paris in 1839, exposing 30 positive images on paper. Since then photography has taken giant steps, to the point that in recent years the quotations of international masters, as well as those of emerging artists, have skyrocketed. Photographic works are exhibited in the most important museums and in the largest art exhibitions in the world and today we can speak of artistic photography as a discipline on a par with painting and sculpture. In this context, with a higher than average GPA, a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Visual Art from the University of Florida’s New World School of the Arts and a Master of Fine Arts degree in Studio Art from Florida International University, Jose Luis Garcia broke into in the world of photography, taking unconventional images through Xerox art, or the art of copying, with the re-conceptualization of images, in a very personal perspective: “I have often been told by audiences that they have felt excluded from dialogues about conceptual art and artworks rooted in art theory and consequently find it challenging to understand art”, explained Josè “I find that using personal imagery, like family photographs, allows audiences the ability to connect with my work on a deeper more intimate level.“

Jose classifies his work as visual poetry and, because it is of visual poetry, as well as emotional that we are talking about: his art is in favor of a complete identification between art and life that mixes images as if it were a palette of colors.

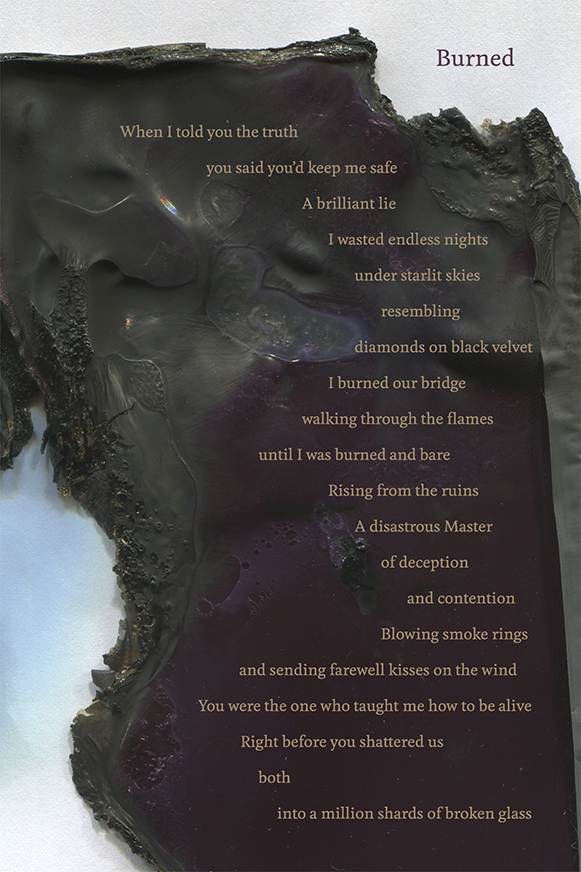

Raised closely by educators, despite having received numerous awards and having participated in various exhibitions, over the years his focus has not been to solely devote himself to his studio practice, but to teach and do research in a community in which there is the possibility to share information that includes different disciplines. Most interesting about it was a project in the context of the Miami Book Fair between 2012 and 2015 in which local artists and writers collaborated on a broadsheet print with written narratives that managed in a way to bridge the gap between photographic art and writing. Jose says: “It is very important for young people to keep in mind that there are so many paths outside of one’s own studio practice that can be undertaken to support the arts or to educate.”

The talent of Jose has already seen him protagonist of three personal exhibitions: Family Aggregate, at The Photography Gallery of FIU in Biscayne Bay; Forget Me Not, at the Urban Studios of FIU Miami Beach and the last one, to which I personally attended, In My Mind’s Eye, curated by Danielle Damas and structured in three parts. It is essentially an exhibition degree thesis. The theme of the thesis is the memory and its social and personal meaning that José Luis Garcia explores through vernacular photography with scenes taken from his family and personal repertoire, treated in an almost diaristic way, through images of holidays, holidays and summers spent on the beaches of Key Biscayne, school photographs and portraits, made with the aim of capturing a memory or an introspective moment that can give comfort and discouragement at the same time. In an Untitled series spanning 1979-1998, Garcia traces the theme of identity and memory in a simple vertical arrangement like a growth chart, in which there are different members of the family.

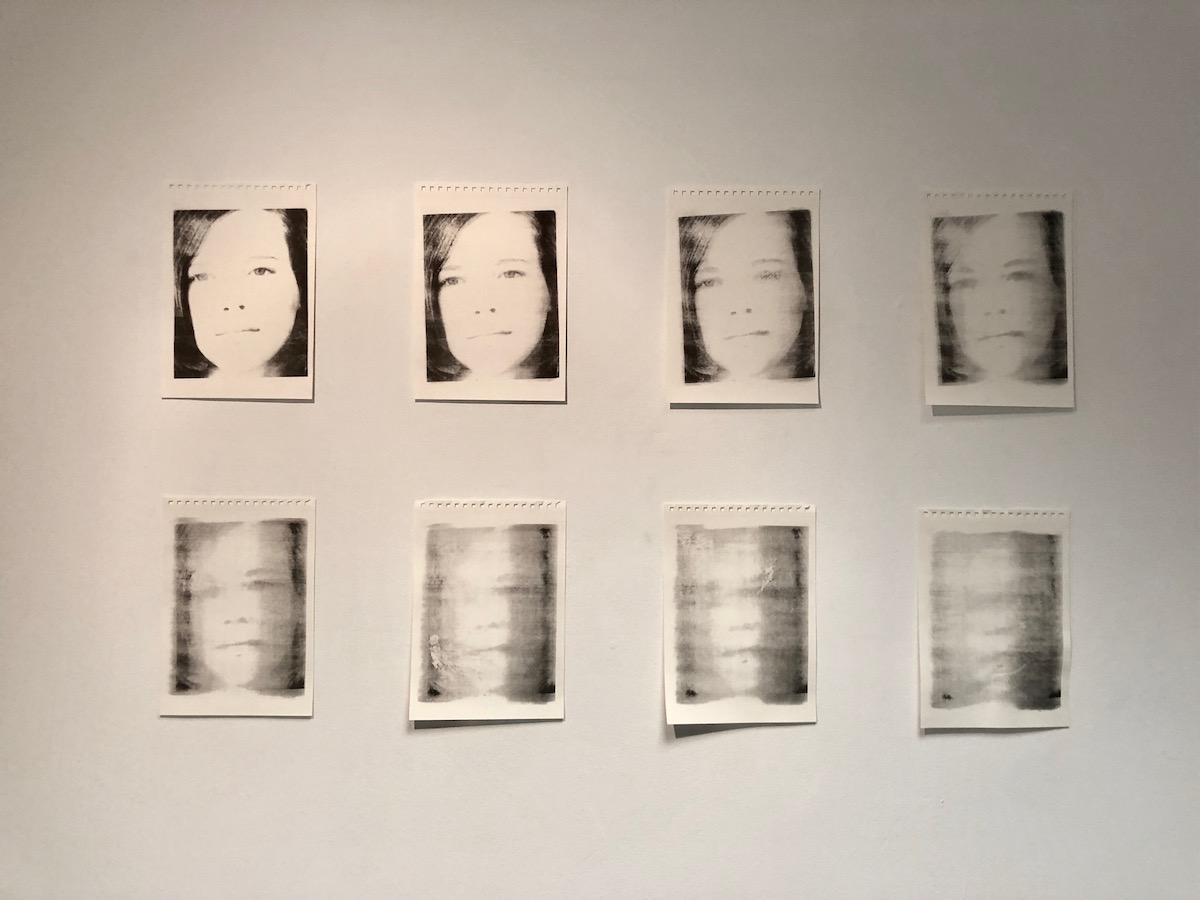

In a different Untitled work, this time from 2008, through the image transfer he composes a wooden triptych (wood skillfully modeled and worked by the artist’s father of Cuban origins) in which three male subjects are represented, highlighting the differences through the passage of time and circumstances. It is from the Gone series, my favorite work, both for the intensity of the subject, and for the artistic work itself, which is the repetition of a beautiful woman’s face, the mother’s face, also Cuban, disappeared in very young age. José, who has his same eyes, repeats his image eight times interrupting the rhythm, just like the process of memory: with each scan or transfer the photograph becomes more blurred, buried, hidden or distorted until you can no longer recognize it. This work represents the memory that fades over time until it gets lost, if it were not for the photograph that keeps its memory alive for eternity.

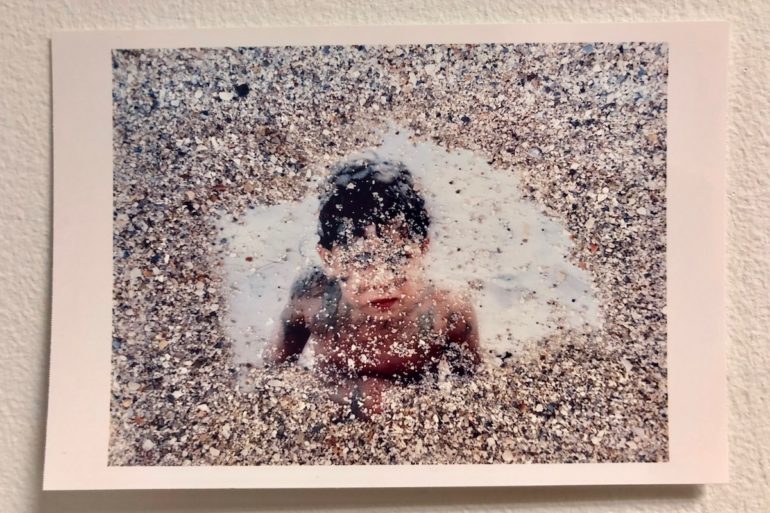

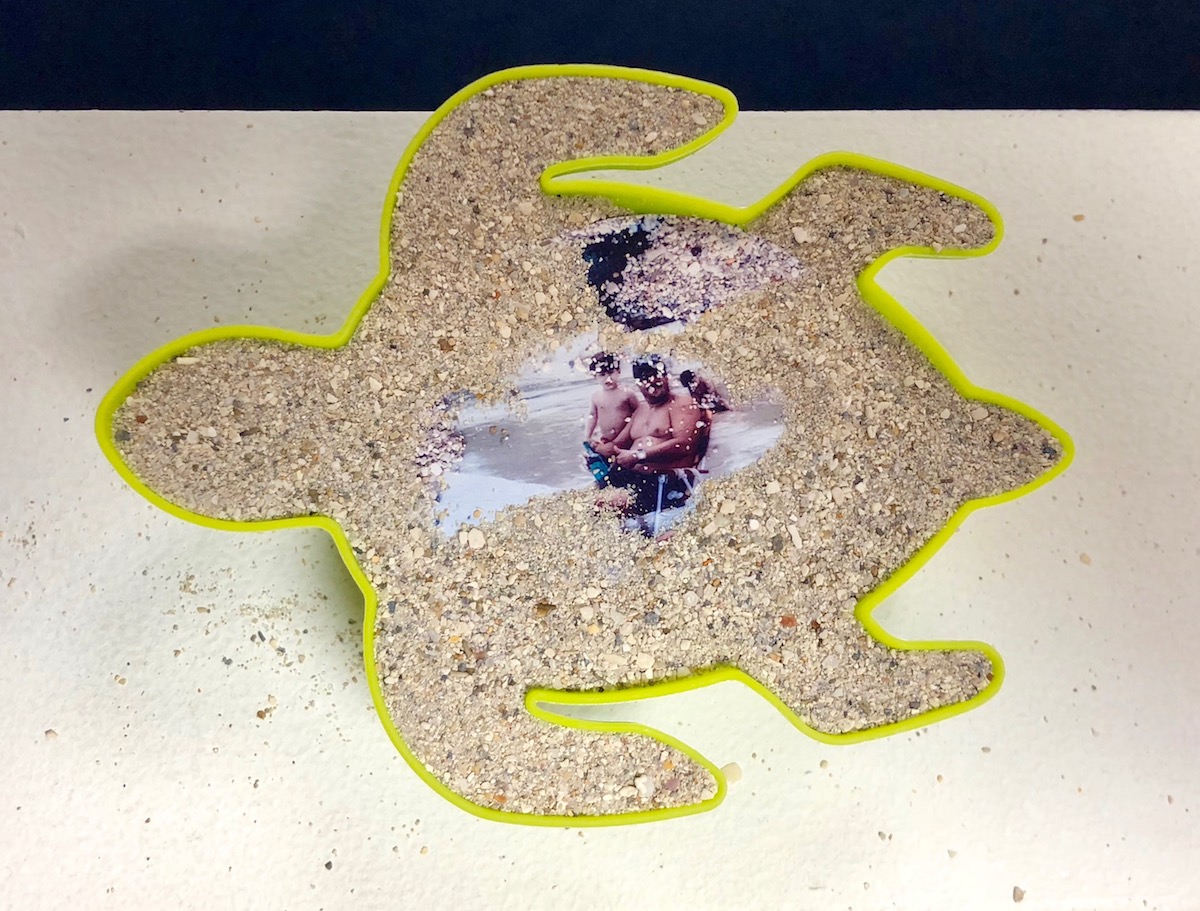

The mother is usually the subject like in his work Quinceañera, this time Garcia highlights the important ceremony of Latin American origin with which we celebrate the fulfillment of the fifteenth year that marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. The work is arranged by itself on an entire wall, almost to want to represent the sacredness, and the repetition is composed in this case of 15 small images. There are also small photographs of the series No place is like a house in which Garcia intentionally covers the images of the houses of the neighborhood, with whom he has been living for 25 years, with an acrylic color with a fluid white effect. The same mechanism is put in place in the images that portray him and his father on the beach. The characters are almost completely erased as with a sort of white-out. This cancellation abruptly exposes the strong bonds between memory or the interpretation of memory and personal identity. In Snapshot buried, a small installation inside a defined space of the exhibition shows through the creative use of classic beach toys for children, specially filled with sand in which Garcia inserts photographs of when he was a child he played on the beaches of Key Biscayne that for him represented the house, the interconnection with the environment that surrounded it.

All small family images, intimate and personal that retrace the sometimes nostalgic and painful path of Josè who decides to make works of art using different mediums and techniques, especially the Image Transfer which allows him to bring photography at a higher level. Josè transfers the perfection captured by photography mainly on paper and wood, creating imperfections and uniqueness with the image transfer, breaking down the surface of the image as if it needed air to breathe, of space around itself to live its own life. This is the case of the photographs in the series of the father reproduced with a missing part in progression and the uniqueness that was created through the transfer.

Works always small and not for a matter of space but because his personal poetry is intimate and can be accommodated in small spaces just as our heart can be in a small part of our body.

To summarize his view as a survivor’s memory, Jose Luis Gracia relies on the quotation of a great contemporary American photographer, Nan (Nancy) Godin, a member of the Boston Five, the so-called Boston Group of Five, who states: “Every time that I pass through something frightening, traumatic, I survive by taking pictures “. And the photos, from the albums and drawers, crammed into old boxes have begun to become the subject of collections, even museums, because the vernacular photography exerts a particular charm in the sphere of collective memory by putting on stage the archetypes of society, touching our unconscious and making the image become part of our experience.

.