This post is also available in:

As unfortunately already defined because of Covid-19, the fourth edition of FACE -Figurative Art Convention and Expo- will not take place but will leave space and an event that will have nothing to envy: REALISM LIVE – A Global Virtual Art Conference – the great online event (October 21 to 24, 2020) which will be attended by the greatest characters of the realistic art-figurative scene in America and that you can follow comfortably sitting in your armchair at home. The third edition of FACE, however, presented Charles Miano and the incredible charm of the red-chalk in the list of teacher-artists. Recognized “Master Living” by the prestigious ARC -Art Renewal Center- the organization that cares about protecting realism, Charles Miano is the founder and director of the Southern Atelier Center for Fine Art in Sarasota, Florida, opened in 2007, and modeled in the wake of the traditional Italian academy combined with the French atelier, and aims to restore mastery of traditional artistic techniques and discipline: fundamental concepts to be able to learn the essential value of the basics of drawing for the development of artistic creativity.

Charles Miano defines himself as an old-fashioned, artist, a person who needs to get to the bottom of knowledge processes whether they are technical concepts or cultural notions. In fact, during his demos, both at FACE, where he represented the beautiful Mardie Rees, his friend and successful sculptor, and during the various “global” demonstrations for which he synchronizes people from all over the world (the last of which was for the GAGE Academy in Seattle) while painting his portraits he combines notions of art history, to various anecdotes interspersed with Italian artistic terms, as a good Italian of old genealogical origins. A characteristic that sets him apart along with his fun way of doing things that Charles is keen to point out: “it is essential to learn while having fun, it helps to relax”. If, however, in Italy there is a saying that says “L’abito non fa il monaco” (The dress does not make the monk”, which is the American equivalent of “Don’t judge a book by its cover”, this is not the case of Charles Miano, who even in appearance reminds us of the painters of the past because of his greedy mustache and the hat that recalls the French beret: omnipresent.

Born in Buffalo, Miano began his studies in the 1990s at the New York Art Department where he was joined by Allen Boyle, a famous Rembrandt scholar, and Korean artist Tim Cho. He then attended classes with the illustrious Nelson Shanks at the Incamminati Studio in Philadelphia and then moved to Italy to attend the Florence Academy of Art in Florence. Although he founded his school in 2007, Miano has never stopped learning and has attended the studies of the greatest contemporary masters among them: Steven Assael, Robert Liberace, Mary Minifie, Dan Thompson, Stephen Perkins, Huihan Liu and Zhaoming Wu. The latter are Chinese masters who had a great influence on Charles Miano whose brushstrokes today are based on an in-depth study of oriental calligraphy and Chinese painting. His passion for the study of the classics then led him to copy live works of art from the old masters in some of the world’s most important museums including the Louvre, the Uffizi and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Always in search of artistic excellence, however, Miano reiterates that the most extraordinary form of teaching is offered by nature because, as he himself says, quoting a phrase by Leonardo da Vinci: “Nature is the source of all true knowledge”. How can we blame him?

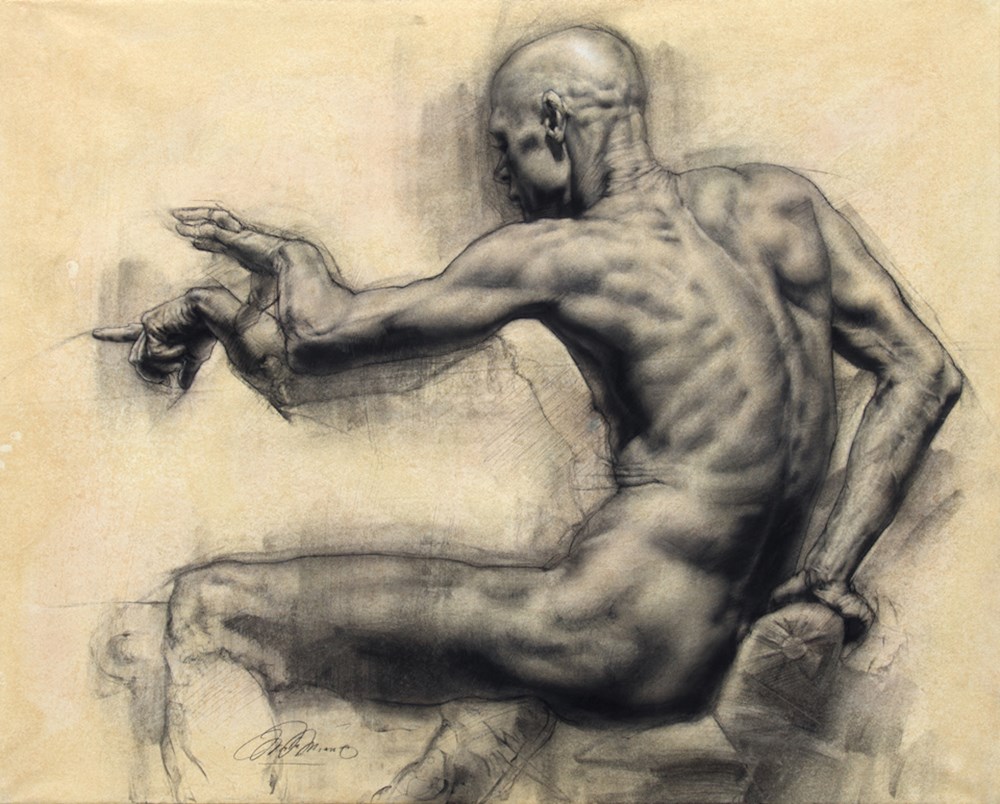

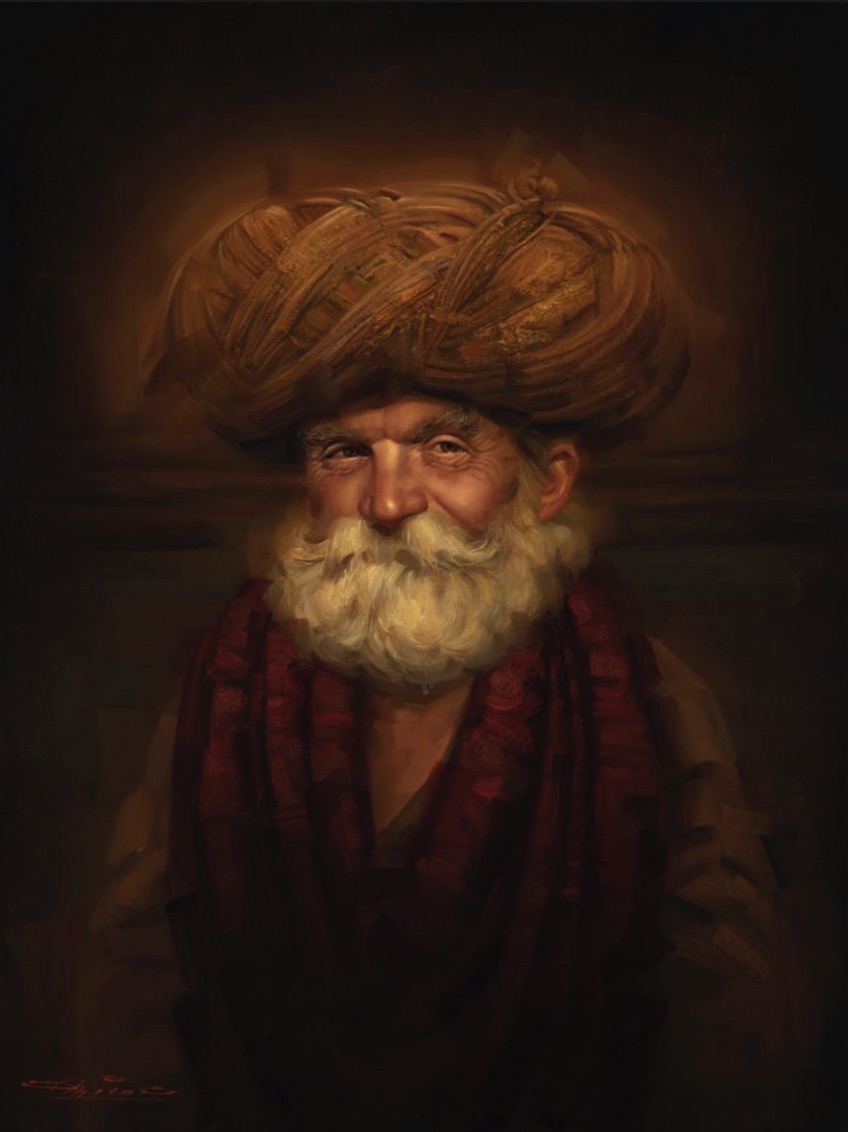

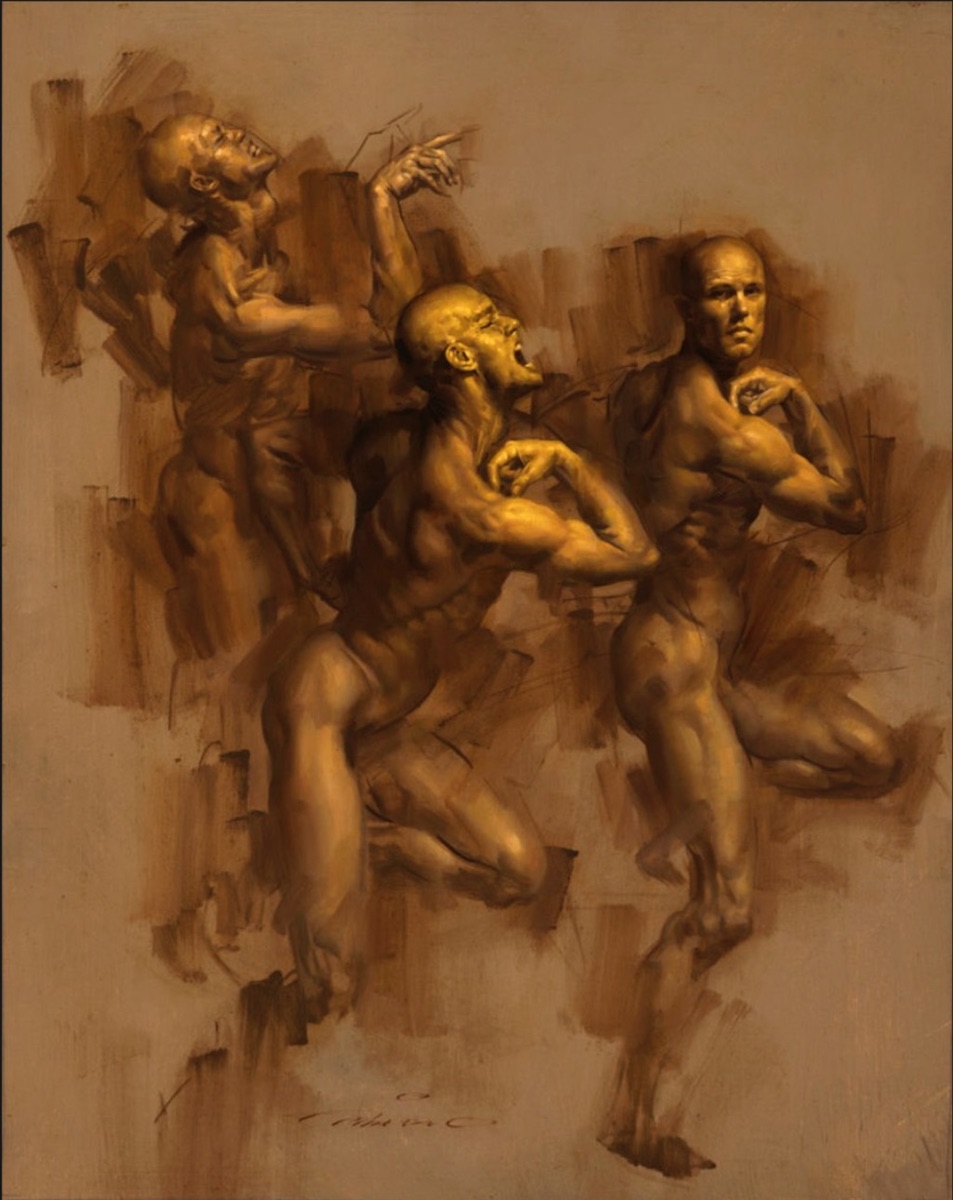

Miano’s style, which is based on the Miano Method, studied and taught by the Master on the basis of the knowledge acquired in all the years of practice, is based primarily on the ability to see and capture “the effect of light”: “light and life are central concepts for my vision”, says the artist. In his works, Miano manages to convey all the passion and power that capture the observer’s attention, rummage through his unconscious and then reach straight to the heart with explosive power. It is difficult to look at his works without being fascinated by them and without trying to learn the technique because through the idea that the artist has of art, he concentrates exclusively on the essentials of the represented subject, without dwelling on useless photographic details, managing in this way to get straight to the soul of the represented subject. A concept that is just as easy to understand as it is technically difficult to put into practice.

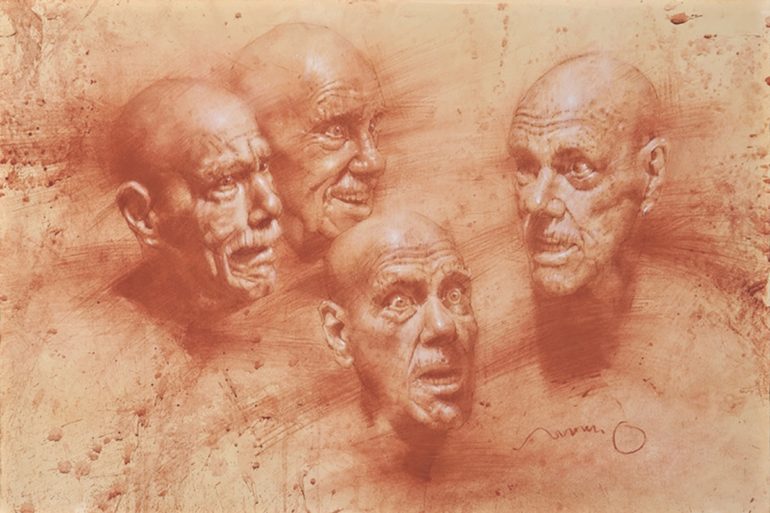

Charles Miano’s is often called a “Visual Poetry” because of the use of red chalk about which Charles declares: “I use it more for painting than for drawing”. When he draws he does so with broad liberating gestures that refer to the rituals of Oriental culture. It is as if the artist used it to capture all the energy that he manages to make converge in the lines of colour, sometimes denser and sometimes more delicate and that he balances through the dynamic use of light and shadows, letting the skill with which he coordinates the complex relationship between hand and eye emerge. Charles is a skilled artist with all mediums, whether charcoal, pencil or oil, with which he often organizes courses lasting a few days on the representation of tronie. The tronie are the famous characters painted both in Dutch painting of the Golden Age and in Flemish Baroque painting and are portraits, which do not refer to particular people but in which a facial expression or costume is highlighted.

But it is above all in the use of red chalk that Charles Miano surpasses himself, succeeding in releasing all his expressive power that emerges in the artist as the result of an inner struggle that takes place between emotion and artistic rigour. Speaking of artistic tastes when asked which is your favorite artist and why, Miano mentions Rembrandt in “The Return of the Prodigal Son”: having seen it back in 2001 at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, I don’t go to much into the reasons for the choice of this work. Rembrandt composed several versions of the “Return of the Prodigal Son”, but in one in particular – the one from which he took his cue from a woodcut drawing made by Maerten van Heemskerck, of which he owned several works – Rembrandt exemplifies his version of art through the use of chiaroscuro and the use of warm colours, probably spread with a spatula, to which he added very thick and wide layers of impasto: few colours that manage to highlight a dramatic and at the same time moving scene, slightly different from the one mentioned in the Gospel according to Luke.

The work composed between 1663 and 1669 is a work of unconditional forgiveness, at least on the part of the father. The painter composed the work at the end of his years, when despite the poverty of the last unfortunate period of his life, he decided to continue painting. Among the many themes he could choose, given that in 1600 the popularity of Dutch theatre and art were at their peak, he opted for this work, almost as if he wanted to make a gesture of repentance, for him who led a life as a sinner. Charles Miano has recently collaborated with Pierre Guidetti of Savoir-Faire, official dealer of the magnificent Sennelier colours, to compose a series of pastels and sanguine used by the Maestro and available for purchase directly on the Southern Atelier website: the Miano Master “Red Chalks” Set. For those interested in taking Charles Miano’s courses, now also available online, you can consult his website at the link: https://southernatelier.org.

(from the title: Expressions by Charles Miano, 2010. Red chalk on paper. 38.1×61 cm)

.