This post is also available in:

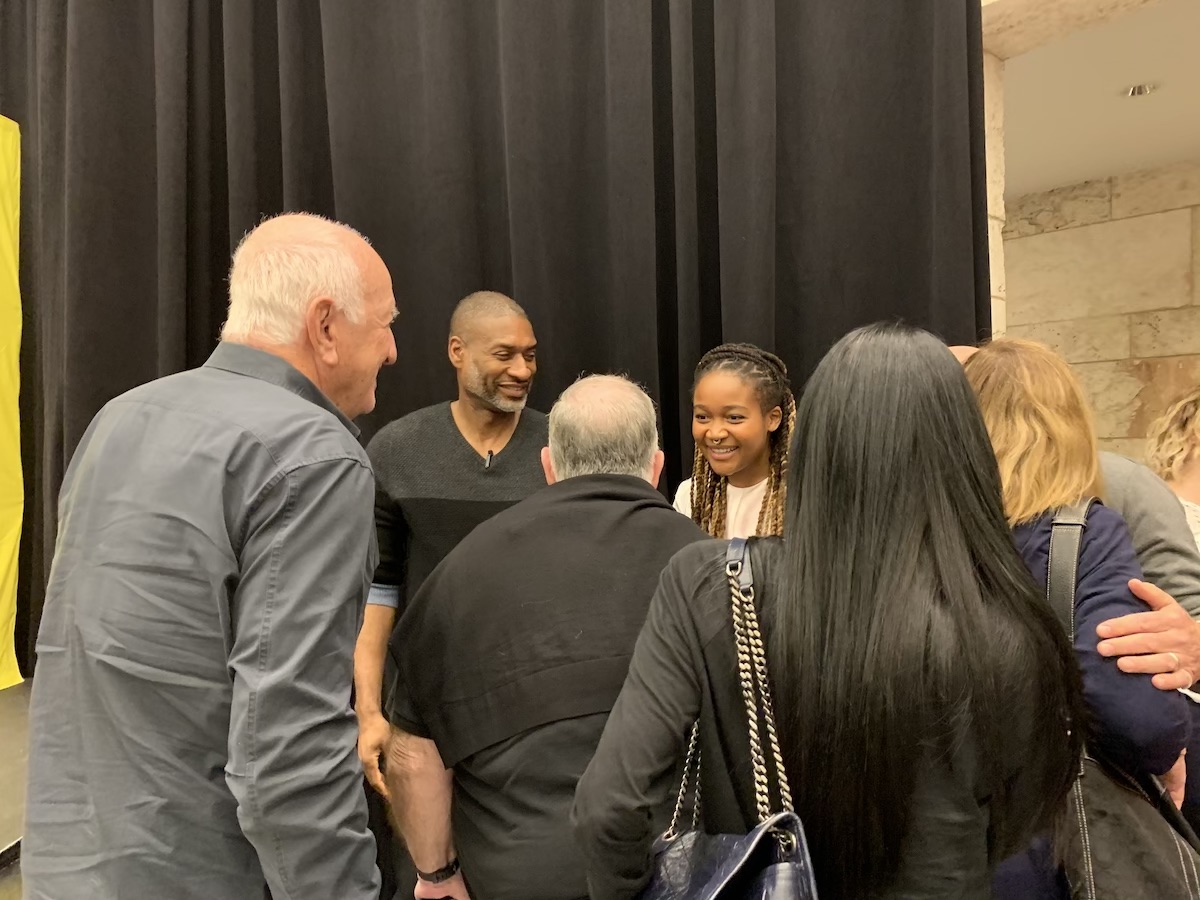

Being invisible and having a voice. This is the theme of the February appointment with Curator Culture at The Bass Museum in Miami Beach that hosted The New York Times writer, journalist and editorialist Charles McRay Blow and Kimberly Drew (aka @museummammy), art curator, writer and social activist, interviewed by the inevitable Tom Healy.

For how long will America continue to buffer the horror of its racial history, considering it as an unfortunate succession of violent episodes that date back to the times that were? How long can we still talk about American history, neglecting the horror and the wickedness of people stolen from their origins? For how much longer will we witness the brutality of the racial murders and the fact that their killers are acquitted still highlighting today the long trail of violent persecution of African Americans. How long will black culture still have to struggle, in America, in Italy, in the world to be part of the history of art? Black culture must emerge like the white one. It must have a voice, have the opportunity to study art, to be part of the history of art. How many works represent the blacks, how many black artists can boast of the history of art? Very few or none in the past, none that has earned the importance of a white. We believe ourselves openminded, avant-garde and unsurpassed, yet we are at the gates of two thousand twenty and we are, paradoxically, still talking about whites and blacks. We must look with clarity and horror at the story of George Stinney, Emmett Till, the Jim Crow Laws or the Tulsa Massacre. We do not talk about the Middle Ages, we talk about years, a few years ago after all barbary and lynching as a great American limitation to maintain white supremacy. A supremacy that in fact should no longer exist.

It’s applicable to humanity the concept that the French philosopher Alain Badiou makes of black: a eulogy of black as non-color because able to summarize them all, from the alternation between darkness and light, chiaroscuro and contrasts in a world that prefers the colors, the nuances, the compromises and in the same way the white represents a non-color but also the whole of all possible colors: to lighten, enlighten, highlight. And like the French word noir, it also represents darkness, so the human mind tries to wriggle away wandering in the dark to the total cultural and social drift, in the refusal of the black, who in fact lives there. In a world of imposters and improvers, as Kimberly Drew says, it is necessary to find the balance between black and white without being afraid to put them close; the split that allows us to approach them as a complement and not as an antithesis. a bit like Supremacist Black Square, by Kazimir Malevich, made in the middle of the First World War, in which the artist paints using a mixture of colors where black is absent and is always Malevich’s work composed in 1918 in which it represents a unthinkable canvas, a white square on a white background. Because we call white, with extreme lightness, everything that appears as the clearest point of the visual field, even if two whites rarely coincide, one is white and one is black.

.

.