This post is also available in:

Eric Rhoads and Gail Sibley are a truly exciting pair of presenters who were able to capture all the sympathy of the audience during these three days of the convention. As a seasoned entertainer with strong entrepreneurial qualities, Eric Rhoads’ versatility was well matched by the sponteaneity and enthusiasm of Gail Sibley, Editor in Chief of Pastel Today, who completed her first experience as co-host of the event.

It was Pierre Guidetti, well-known face of Savoir Faire, among the event’s platinum sponsors, who opened the third and final day of the second edition of Pastel Live: the event entirely dedicated to pastel and declined in all its artistic expressions.

He did so as usual in his style, with an interesting lecture in which he disquisitioned about the origin and geography of colors, including the precious ochre, and lapis lazuli. In addition to being a great speaker, Pierre Guidetti is also an ambassador of historic brands, which have been able to make the quality of artistic materials their life mission. These include Fabriano, Cretacolor, and especially Sennelier, with whom he began the Savoir Faire adventure in America forty years ago.

Guidetti also, on the basis of his vast technical knowledge, answered questions from the audience by dispensing practical advice to the participants, who know they can always count on his valuable technical information, calibrated with just enough technicality to better help them understand the functions of different materials.

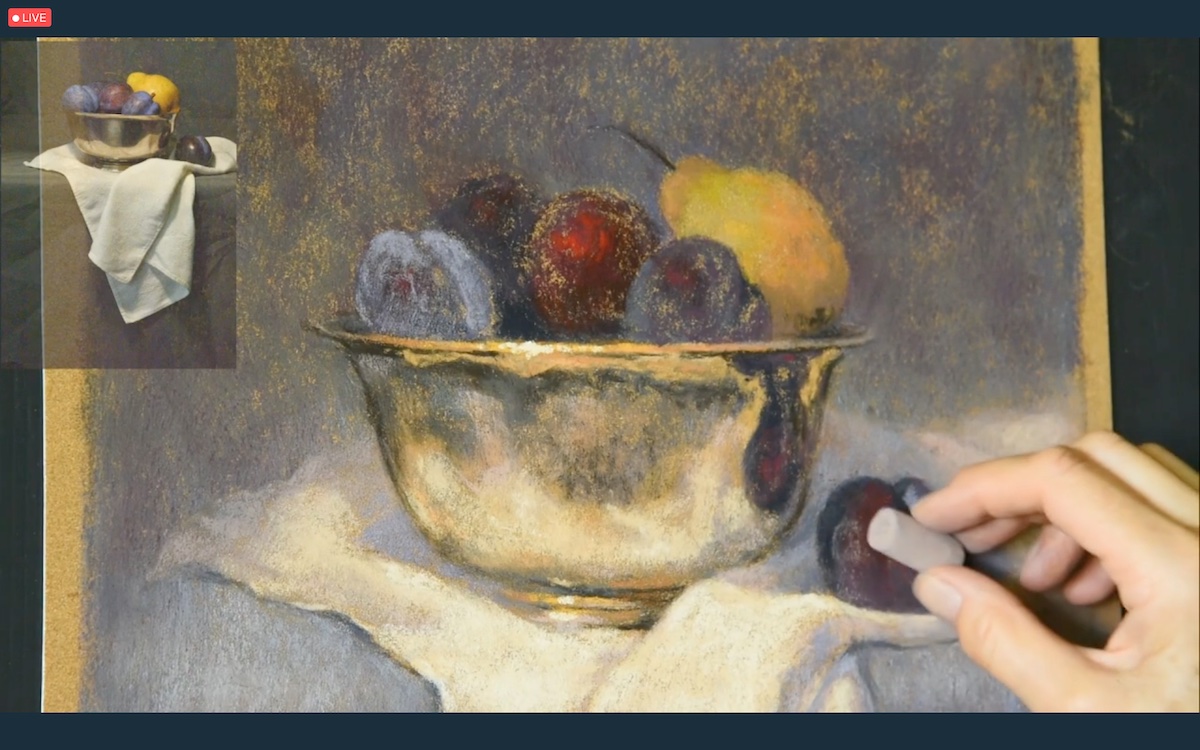

The demonstration sessions got into full swing with Canadian artist Susan Godbout, who created live a still life work. In creating the scene, consisting of a copper fruit bowl containing plums and arranged on a cotton dishcloth, the artist managed to capture all the different reactions of materials to the reflection of light on surfaces. Reflection that, as is well known, is defined by precise rules that the artist has refined over time thanks exclusively to the representation of objects from life. “Painting from life is very different from the representation of photographic images. After only 30 minutes, you can begin to see much more than a photograph could ever show,” the artist said.

The search for light, which slowly emerges from the texture of different materials, is after all the same reason that drives the Canadian artist to paint his live subjects.

Before making the pastel drafting, Goudbout dwelt on the importance of the lines in the construction of the composition. Lines that are distinguished by their function: vertical and horizontal ones help provide solidity to the composition; diagonal lines direct the viewer’s gaze toward the subject; and curved ones bring much-needed imagination to the perception of the painting. Having established the fundamentals of drawing Godbout organizes colors by tonal values.

Goudbout’s paintings are characterized by the presence of small areas of intense warm color-usually red or orange-that the artist spreads exclusively with soft pastels. “Soft pastels offer a special experience because they allow for more delicate color transitions and textures,” said the artist, who, to best render the perception of metal, highlights its highlights.

An artist originally from Georgia, Karen Margulis is known in the environment for her distinct ability to make art simple and accessible to anyone. The practical example was today’s demonstration, during which she provided detailed information on how to approach her artistic technique. A particular technique he also employed in the making of today’s demonstration in which he depicted one of his favorite subjects: white flowers against the background of a seascape. Margulis created the composition from a vibrant watercolor underpainting: an actual vibrant painting with which he made the drawing by proceeding in the application of large masses of color. “Watercolor is the most fun and magical part of the artistic process because it offers a completely different effect and allows me to connect all the dots of the pictorial narrative. The unpredictability that characterizes the medium also offers interesting flourishes in the composition,” said the artist. Margulis routinely takes much more time in underpainting than in finishing the pastel composition, because, as she puts it, “a well-executed underpainting offers guaranteed results.” She also loves the effect of uderpainting on the final composition, so she lets it show through on the paper. However, her artistic process requires some special arrangements, first and foremost the use of an appropriate paper support that can support the multiple successive layers of pastel in which the artist searches for the compositional rhythm that orchestrates the set of elements.

In illustrating her process, however, Margulis emphasized that in reality there is no right or wrong way to proceed in the compositional process, but as in all things, it is necessary to dare and experiment, even with the use of dark colors, which most of the time are intimidating, but which allow all other values to be established accordingly.

The beauty of the demonstration sessions also lies in the differences in the artists’ styles and their approach to the audience. Some people are gifted with great verbal communication skills, while others prefer to let the composition speak for them, merely clarifying the essential points of the compositional process. Richard Wilson, a man of great artistic and human sensitivity is among the latter.

We at Miami Niche interviewed him exclusively for Realism.Today and you can read the interview at the following link:

https://realismtoday.com/pastel-painting-between-dreams-and-fulfillment/

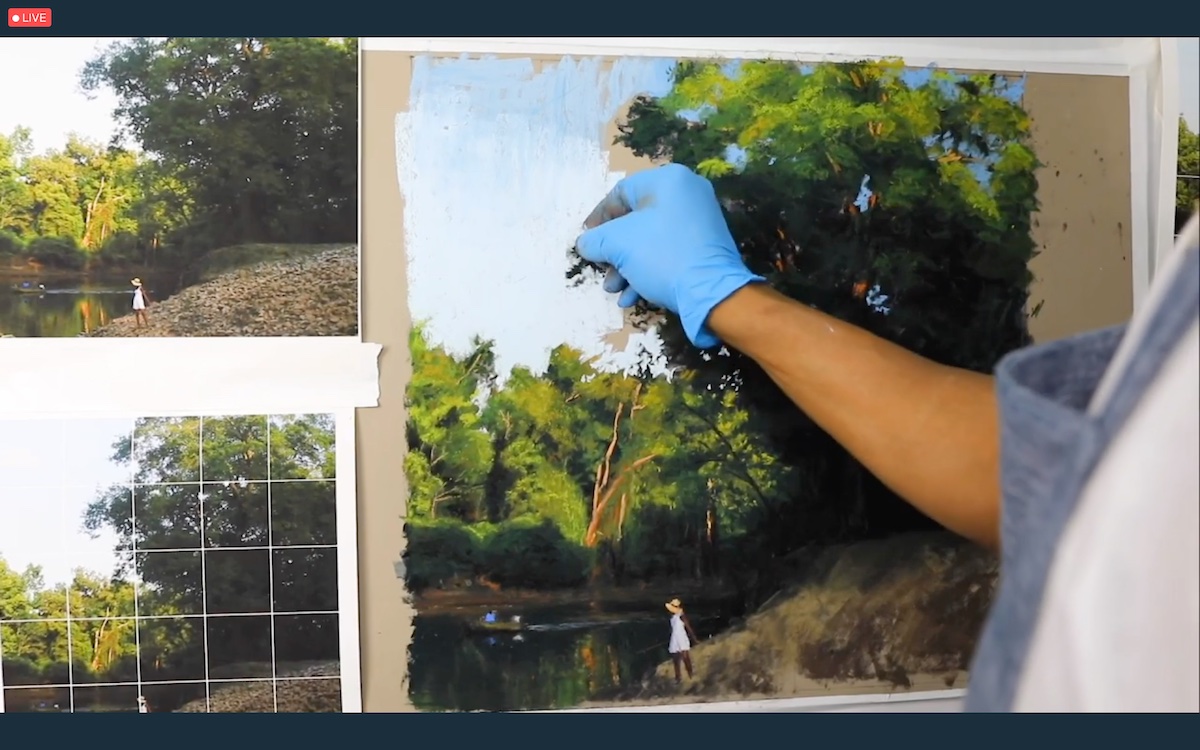

For the demonstration session, Wilson made a foreshortening of a magnificent wooded river landscape in which a figure is visible: it is one of the artist’s three daughters whom he usually depicts in his landscape paintings. In drafting the drawing, the artist helped himself to a compositional grid: a means that he recommends, especially for those approaching landscape painting for the first time, and that makes it possible not to lose sight of the composition of the section in relation to the overall picture. In the drafting of the pastel, the artist instead began with the large color forms in which he worked in sections, reaching, for each, discrete levels of detail from which he moved progressively to the completion of the painting as a whole. The definition of the sky, which also proceeds by negative forms, through the majestic tree that dominates the scene -which he achieves by applying five layers of color- together with the effect of light on the foliage and the reflections of nature in the water, bring the composition to a higher level of representation that allows the viewer to fully immerse himself in the nature of the landscape. The artist usually amalgamates colors using simple charcoal that he moves following the natural rhythm of the compositional elements.

“I love teaching in a fun way,” said artist Brenda Boylan whose sonorous laughter makes her a sunny character like the shades of yellow used in the composition. The artist, recipient of the “Eminent Pastelist Designation from the Pastel Society of America,” made the excerpt of a vine in Portland, Oregon, using photographic reference and focusing on the play of light and shadow. A play that the artist rendered in a particular way by selecting for the block-in of the masses different shades of only two colors: four shades of yellow for the light areas and four shades of blue for the dark areas. Shades that he later blended with denatured alcohol keeping the subdivision of colors alive and thus preventing the mixing of colors in the subsequent pastel layering stages. “Everything that is affected by the sun will have a lighter value than what is in shadow,” the artist said to explain her thought process, the same with which she later laid down multiple layers of color that brought out compassion in a three-dimensional way. Boylan’s was a very unique approach both because of the unusual choice to focus the viewer’s attention on the sides of the paper-rather than the middle as is usually the case-and because of the ability this artist possesses to translate the mental image onto the paper based on the initial drafting of only two colors. An approach that can on the one hand facilitate the observer in the drafting of tonal values and on the other hand can create some problems for those who do not possess Boylan’s ability to see the work in its entirety. Problem the latter, however, which the artist amiably solved by advising to think of the making of the composition as if it were the composition of a tree.

Already the protagonist, during the beginner’s day of a demonstration session entirely dedicated to materials, Australian artist Lyn Diefenbach created a composition of an emblematic flower: the Strelitzia, also commonly known as the Bird of Paradise.

This is not a random choice and one that distinguishes the works created by Diefenbach, who, with 30 years of experience behind her, has won prestigious awards precisely for the masterful realization of her particular, carefully chosen subjects.

The artist, who relied on non-detailed checkering to execute the drawing, began the demonstration from the negative drafting of the background, taking care to turn the sheet palette countless times to allow the pigments to enter the fibers that make up the paper. To create the depth of the background he used two colors: dark green and dark red, the combination of which resulted in a color deeper than black. He subsequently superimposed the multiplicity of shades that make up the flower, varying their color temperature, blending them and making small tonal transactions that made it possible to achieve the perfect chromatic harmony inherent in the nature of the flower.

A sublime demonstration that captured the enthusiasm of the audience also thanks to the artist’s ability to realistically render both the dewdrops, captured by small touches of color, and the botanical structure of the flower, obtained by mixing the color values of the petals with the cream-colored pastel. A combination of factors with which he also highlighted the flower’s bizarre shape.

Albert Handell could only be, to quote a phrase from artist Lyn Diefenbach, “the perfect conclusion to a perfect event.”

A living legend in the pastel world, Albert Handell, has a disarming simplicity both in the way he is and in the way he imparts suggestions that are anything but obvious. Credit surely goes to his 50 years of experience in the pastel world. A factor that over time, and unlike all other artists, has enabled him not to have to “organize” the color box by tonal or chromatic values.

In his demonstration, Handell was a flood of information: all equally important, revolving around the world of art but pushing the listener to go further; for the realization of his demonstration session, he depicted his favorite subjects: trees. A subject that Handell particularly loves and which he said he began studying in the 1970s and which still, decades later, excite him both in the spiral movement of the foliage-which implies the application of perspective principles and the conception of rhythm, which according to the artist inhabits each and every element of nature-and in the structure of a simple twig underlying the laws that govern the direction of light.

Anyone would stay hours listening to Albert Handell’s lectures and would fill notebooks if one kept track of his notes among which he mentioned: the importance of lost and found edges (especially in the making of landscapes); the pressure exerted on the pastel (which must be as light as a butterfly’s or as stinging as a bee’s if necessary); the importance of certain compositional details (which have their own rhythm untethered from that of the composition). But Albert Handell’s greatness also lies in the simplicity with which he summarizes the pivotal concepts that inspired him in life as much as in art and that can be summarized in Mohammed Ali’s famous phrase: “Float like a butterfly. Sting like a bee. You can’t hit what your eyes don’t see” (“Fly like a butterfly. Sting like a bee. You can’t hit what your eyes don’t see”).

The third day of Pastel Live ends today and we look forward to seeing you numerous next year for the third edition of the event that will be online from August 17 to 19 2023, with the option to sign up for the optional pre-event day (August 16). The Streamile Publishing team looks forward to seeing you in large numbers and with the same enthusiasm as usual, but in the meantime we look forward to the next event: Realism Live, which will be online from November 8 to 11: the lineup is already packed with events, don’t miss it.

(on the title: Albert Handell and his final work demonstration)