This post is also available in:

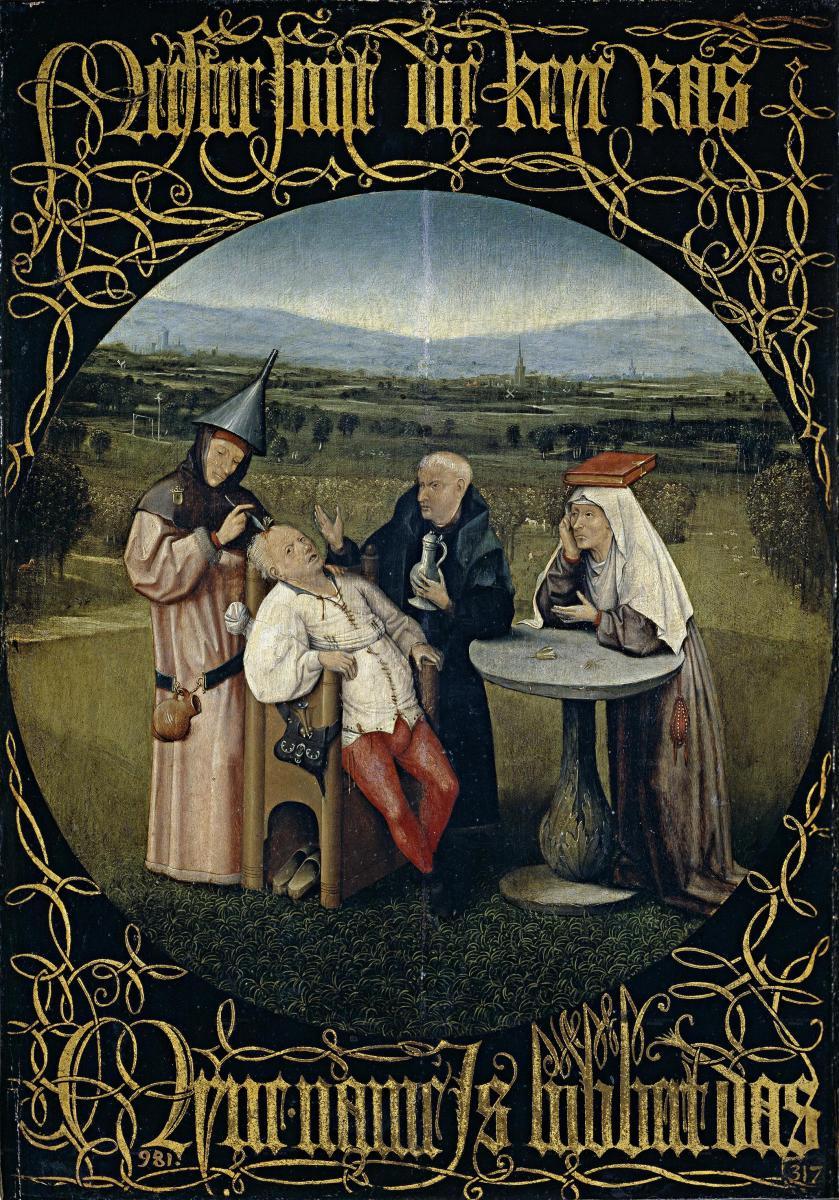

The figure of Anthoniszon van Aken, better known under the pseudonym Hieronymus Bosch, is still shrouded in mystery. One of the greatest and most mysterious, Flemish masters, Bosch has managed to liven up the imagination of scholars and enthusiasts thanks to the stories full of symbolism and mysticism told, with meticulous detail, by each of the many characters, ironic and grotesque, who inhabit his paintings.

Hieronymus Bosch, was born into a large family, probably of humble origins and composed mainly of artists: his grandfather, father, some uncles and brothers were artists and it is in fact attributable to the family environment his artistic training. Bosch was claimed as a painter of Spanish origins because of the use of the surname “Bosco”, imprinted in some of his paintings, but the pseudonym Bosch probably derives from the devotion to the city where the family had moved, in ‘s Hertogenbosch, in the Netherlands. Yet the Prado Museum, in Spain, nevertheless preserves the richest collection of Bosch’s works, with works also present at the Escorial (the political centre of Philip II, a fundamental figure in the life of the artist at a time when religious and political power conferred) while other works are preserved at the Boymans van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, Italy, the Het Noord-Brabants Museum also in the Netherlands, the Kupferstichkabinett in Berlin and the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

Bosch was, with Flemish artists, one of the first painters to use oil: Flemish painters were much sought after at the time because of the mastery with which they handled oil and because of the improvements they made in the period between the late Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance. From the analysis of the works in the quai different elements have been isolated, for example: the plants, the sky, the characters and their ears, it can be said almost with certainty that the various elements are composed of different people in Bosch’s circle. Another confirmation comes from the fact that Bosch was right-handed while some of his works are painted with the left: probably among the artist’s helpers are the same members of the family.

Although he was already an established painter at the time, he married a woman of high society who included him in the “Confraternity of Our Lady”: an association that integrated the cult of Our Lady with charitable activity. Another point in favour, due to the wedding, was the fact that he became part of the high society to which he sold his works freely expressing his ideas, without the need to work on commission, to earn a living. The symbol of the “Confraternity of Our Lady” was inspired by a mystic of the 1300s (Jan van Ruysbroek) who fought against the heretical sects and corruption of the clergy and had the swan as a distinctive element, a bird that appears in some of Bosch’s works as an element halfway between the swan and the goose: pens of strongly contrasting symbolic value and for this reason, considered a sort of mockery of the brotherhood.

Hieronimus Bosch, although always an acclaimed artist, had neither a school nor followers, but rather imitators who copied his style. The demonic fame that Bosch brought with him over time began only after the fury of the Reformed who condemned his works and partially destroyed them. To date there are a total of 25/26 works, some of which are unfortunately kept in a very poor state at the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice and restored later (worth $300,000 paid for $145,000 by the Getty Foundation and the rest by Netherland) for the exhibition celebrating the artist’s 500th anniversary, which took place in 2016 in Den Bosch, Netherland, which however does not own any of the artist’s own work and had to borrow the works from the museum owners.

In 2010 a group composed of art critics and technicians, wood experts, restorers and photographers who, in addition to analysing the works, took macro photographs visible on the infrared by insiders who highlighted the artist’s pentimenti and other details, otherwise not visible, from the observation the visit to the museum, where in addition to the safety distance of 5 feet to maintain, sometimes the reflection of the glass does not allow you to see the painting.

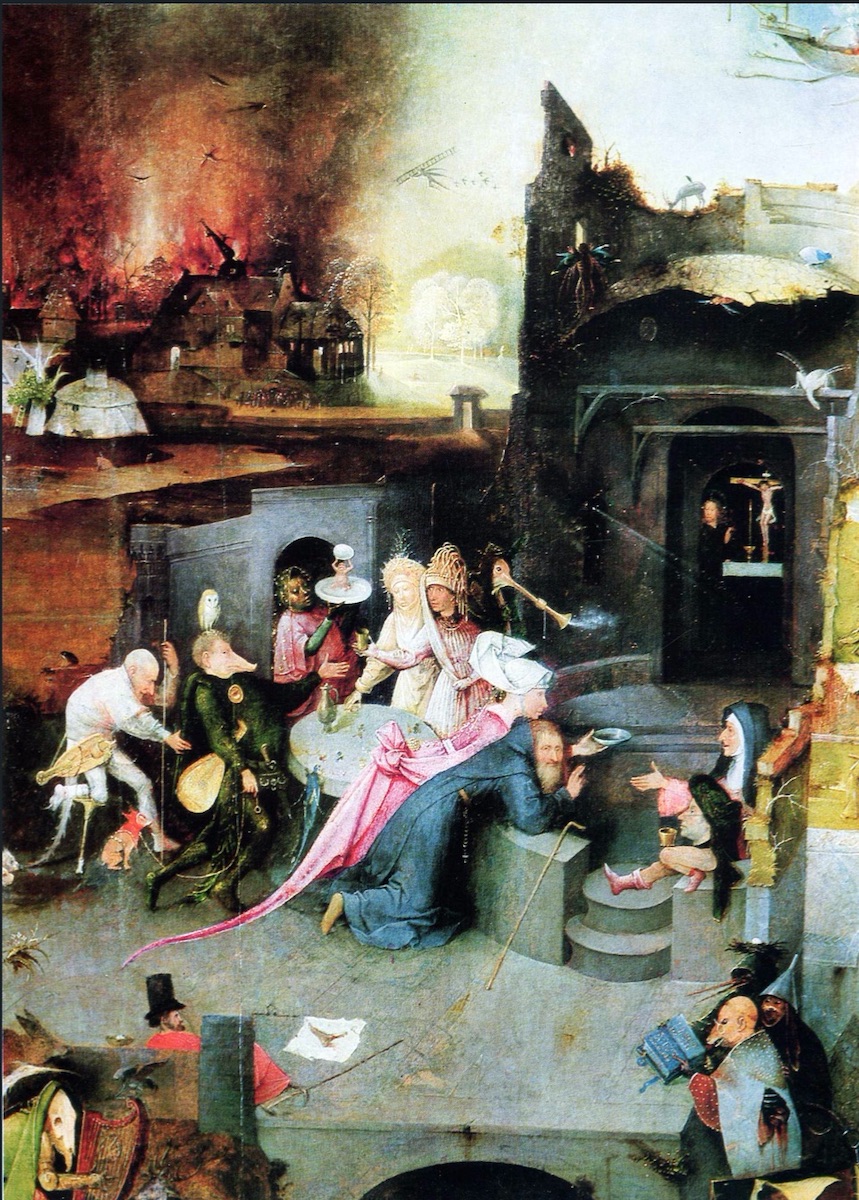

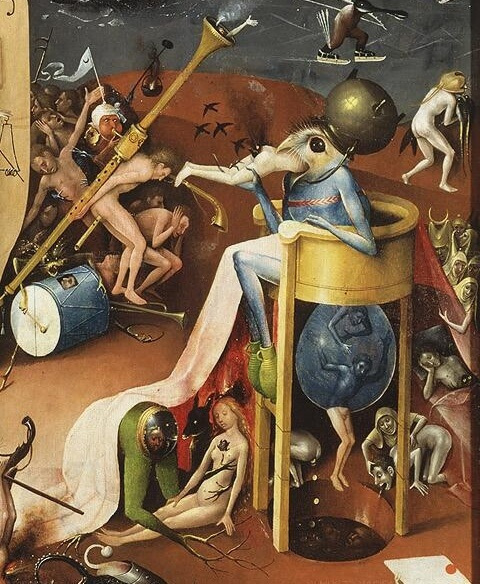

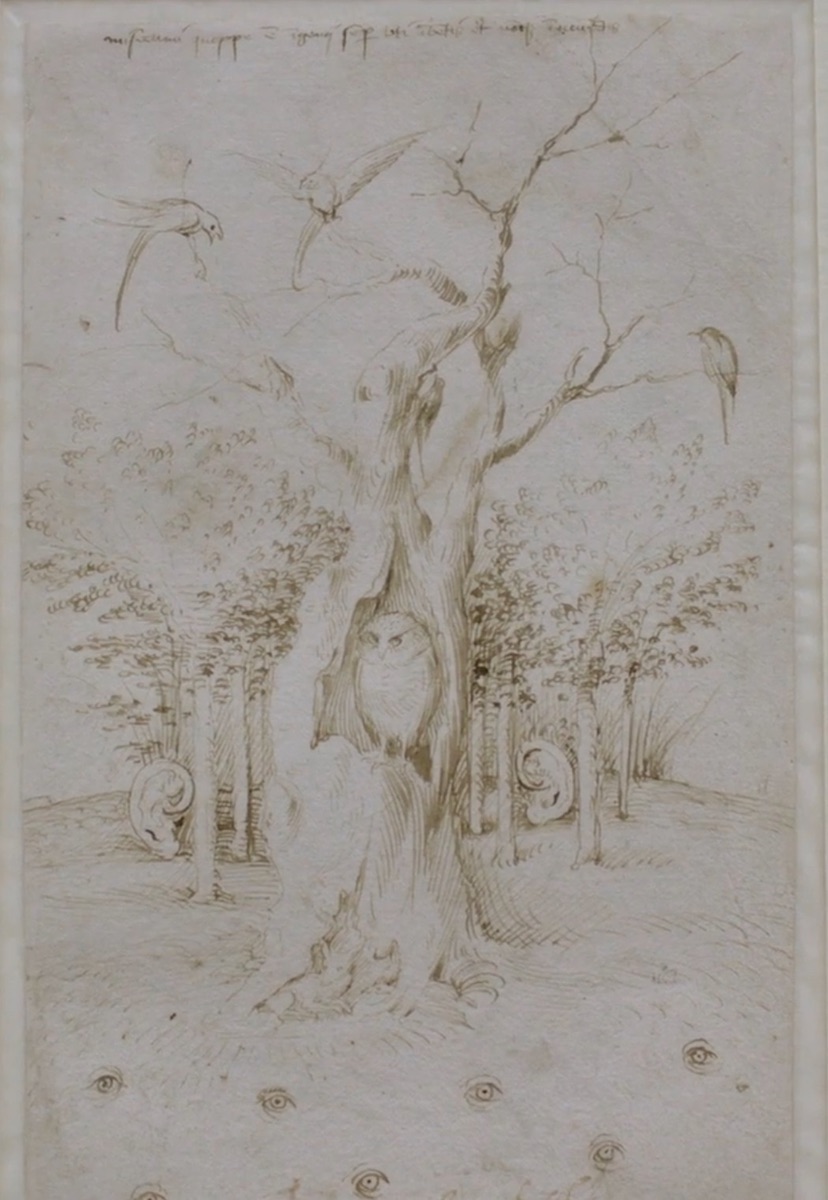

But in the quiet and affluent life that Bosch was supposed to have, very important details emerged that reveal how in truth the artist’s soul was shaken by tensions and emotional storms. In addition to the theme of human madness, one of the themes dear to him is fire. This element refers to a fire that broke out in the middle of the night when he was a child, which devastated much of the city. The event must have impressed Bosch so much that he reproduced it in many panels. Another recurring element with a certain frequency is the presence of owls, animals that were considered to be demonic and of bad omen because they represented darkness and danger. This bird was thought to confer sinister and bad omen connotations, deliberately used by the artist in his works: critics have even aired the hypothesis that behind the image of owls and owls there is the symbolic representation of the artist. There are about 25 of them, almost one for each painting (in addition to the drawings) and they nest everywhere. It is interesting to discover in the different works these nocturnal predators “sent by the devil”: all different and yet all fascinating.

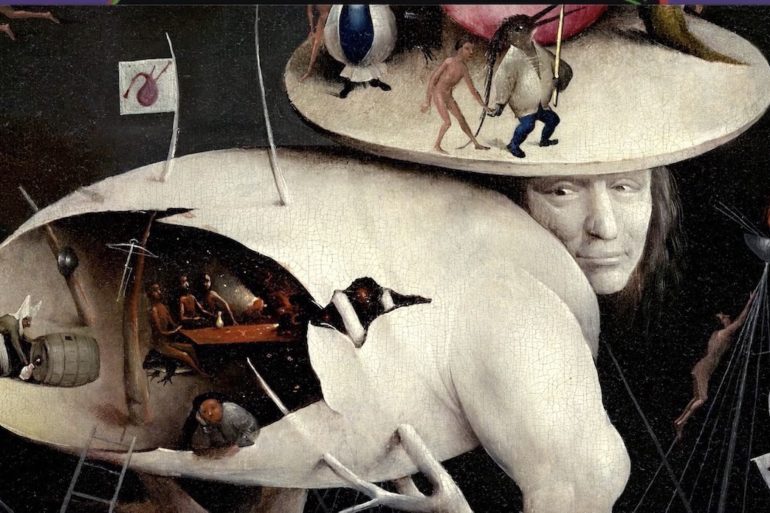

Another theme addressed by Bosch is the Paradise-Inferno dichotomy, visible above all in the triptych The “Garden of Delights”, in which Hell (the panel on the right) represents the apotheosis of Bosch’s imaginative mind in which it is man who must decide which path to follow: Hell or Paradise. Both roads are easy to follow and Bosch’s images are the visual consequence of taking the good road or the bad road, in fact for both the artist shows us the moral consequences of the choice even if in any case there is always a spiral of redemption in his works.

Since many of his works are undated, we proceeded to “read” the lines of the wood on the back of the panel represented. Even if the proportions of the figures are not real, the compositional accuracy, the skill of the drawing, the brilliance of the colours make them timeless masterpieces.

However, his drawings and his pentimenti still leave many questions unanswered because much has been discovered by x-ray analysis and macro photography but it is still not clear what drove the artist to represent those images. This remains a mystery, despite the thousand theories that have been made about it. One of the reasons why Bosch is much appreciated is the quality of his illustrations, the mystery behind each of his details, the “Inventio”, or inventive mind that has elaborated these images and these stories. A brilliant and curious artist with a new particular vision of events, life and religion: one should try to understand to what extent these images have escaped from the creative mind of the artist and his culture, or if rather they derive from the indoctrination of someone.

Among the works are the “Triptych of Delights” at the Prado Museum, “The Haywain Triptych” preserved since 1914 at the Escorial, “Christ Carrying the Cross” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent Belgium, “Ship of Fools” at the Louvre in Paris, “The Last Judgment” at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, “Death and the Miser” at the National Gallery of Art and “Triptych of the Crucified Martyr” at the Academy Galleries in Venice; among the ink and pen drawings is the deserving one: “The Field has eyes the Forest has Ears”, which reads a Latin phrase translated as “Poor is the mind of men. .. always using someone else’s inventions and never thinking about himself”.

In essence, many things were said about him: “there are those who considered him a heretic, those who considered him a madman and those who considered him a hero capable of throwing in the face of the world, through those few works that have remained, the wickedness and bestiality inherent in human nature” as Mario Bussagli, a great connoisseur of Bosch who published a book by Giunti editore, wrote many years ago. I personally believe that his works are a story without end, with attention to the smallest details and the magic of the representation of the characters and their context, able to stimulate the imaginative minds that contemplate him in ecstasy.

.