This post is also available in:

WOW!…what an incredible day.

Only now I can understand, concretely, the enthusiasm with which I have always been told about Plein Air Convention and Expo (PACE).

Imagine being in a charming little town with a typical Western flavor -for those born in the 1980s it is the perfect representation of the American Western- cadenced by the quiet and surrounded by mountains. The favorite subject of the hundreds and hundreds of artists who have positioned themselves comfortably on camping chairs, in front of their easels or sitting on one of the many rocks bordering the river.

Artists who inevitably attracted the attention of local citizens who, accustomed to the daily quiet, stopped to chat or simply observe the artists at work while participating as spectators in the world’s largest plein air session.

The City of Golden was just the first of several scheduled locations.

In the afternoon session, participants put into practice the concepts imparted during the daily demonstration sessions, which focused mainly on the representation of mountains.

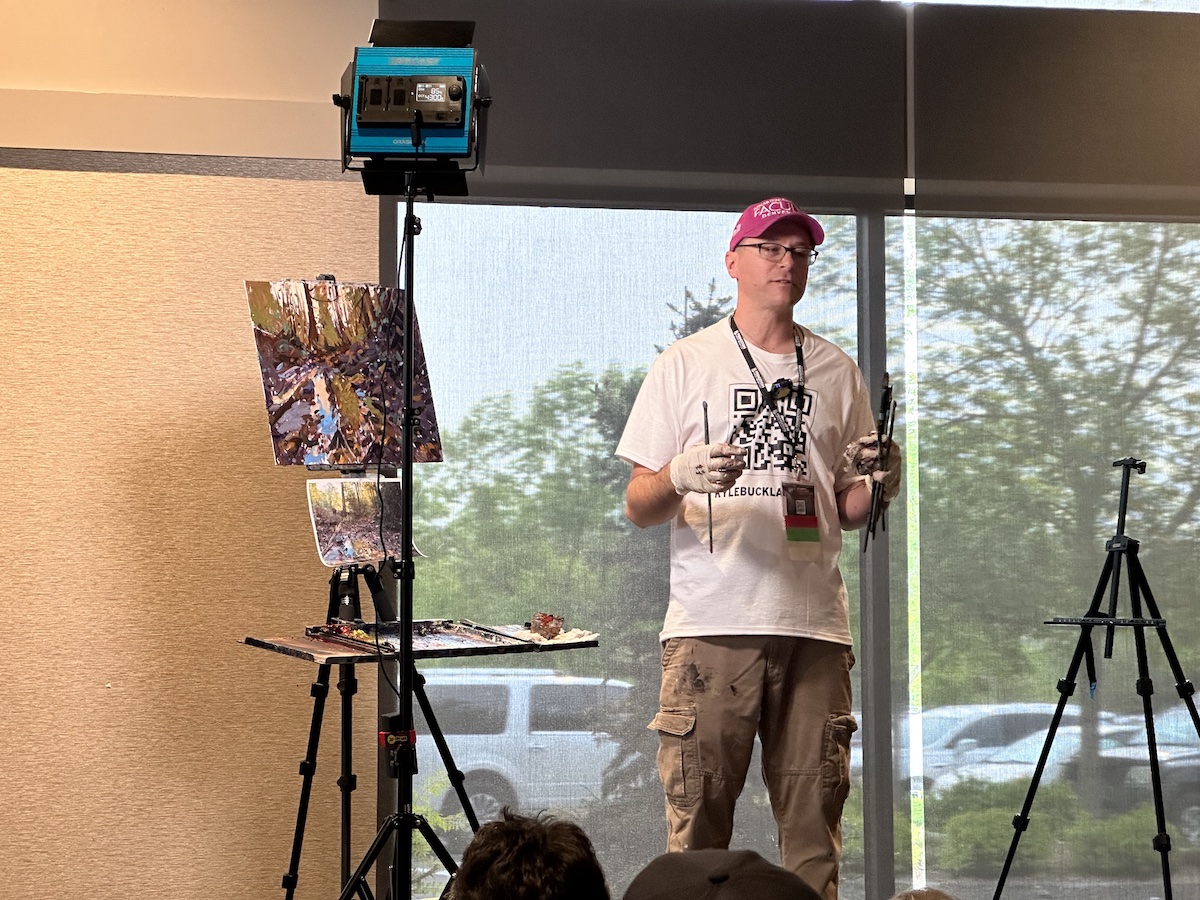

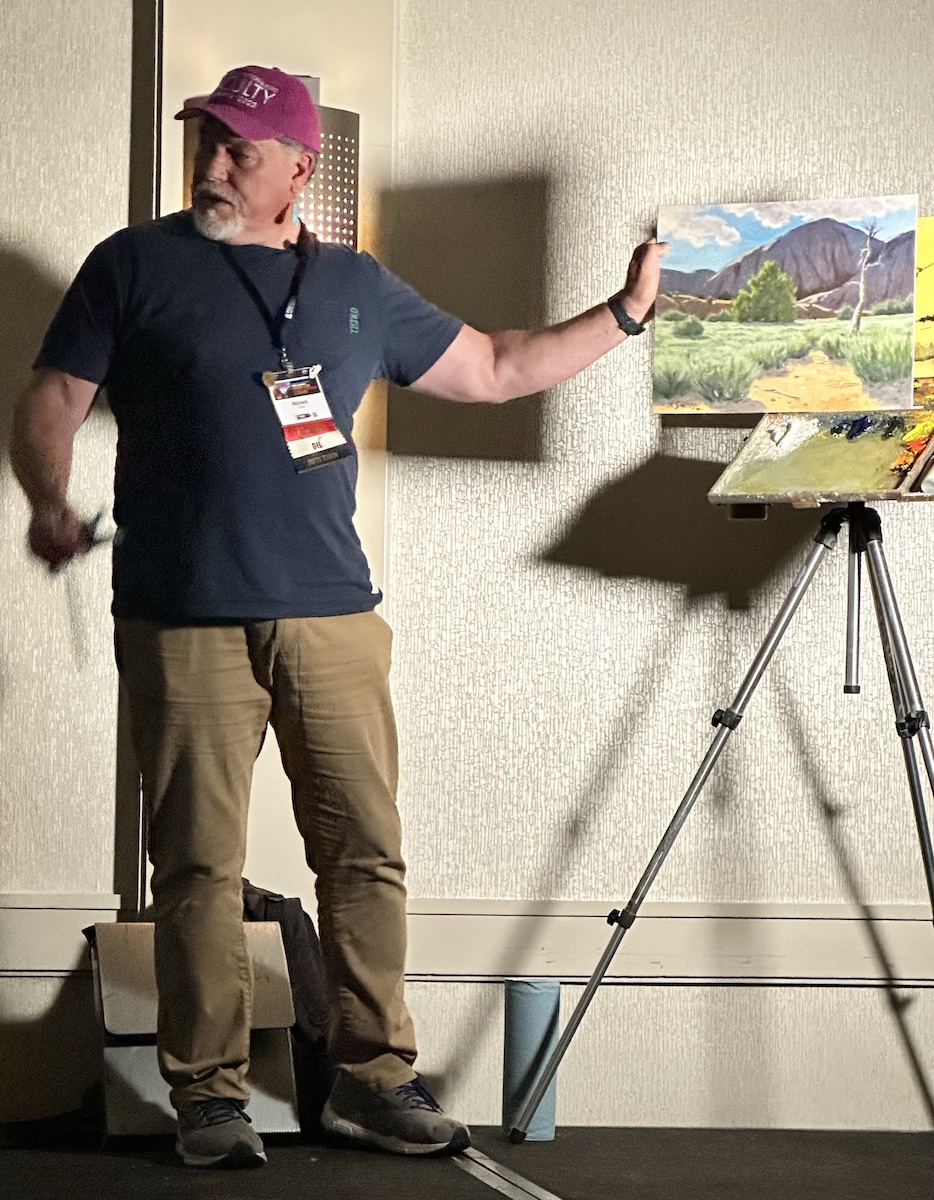

Among them was Jim Wodark, extraordinaire artist who sketched composition from Kevin Macpherson’s renowned grid-based approach. In the demonstration session, he talked about the most frequent mistake made by artists regarding the design that should highlight the mountains and not the foreground, thus re-establishing the placement of the horizon line. Described by Mark Shasha -who in the evening was the featured artist, with Suzie Baker, in the critical session- as a great artist rich in technical skills, Wodark makes lines and edges consistent with his being a painter of nature through organic lines and edges that, he uses as natural contours.

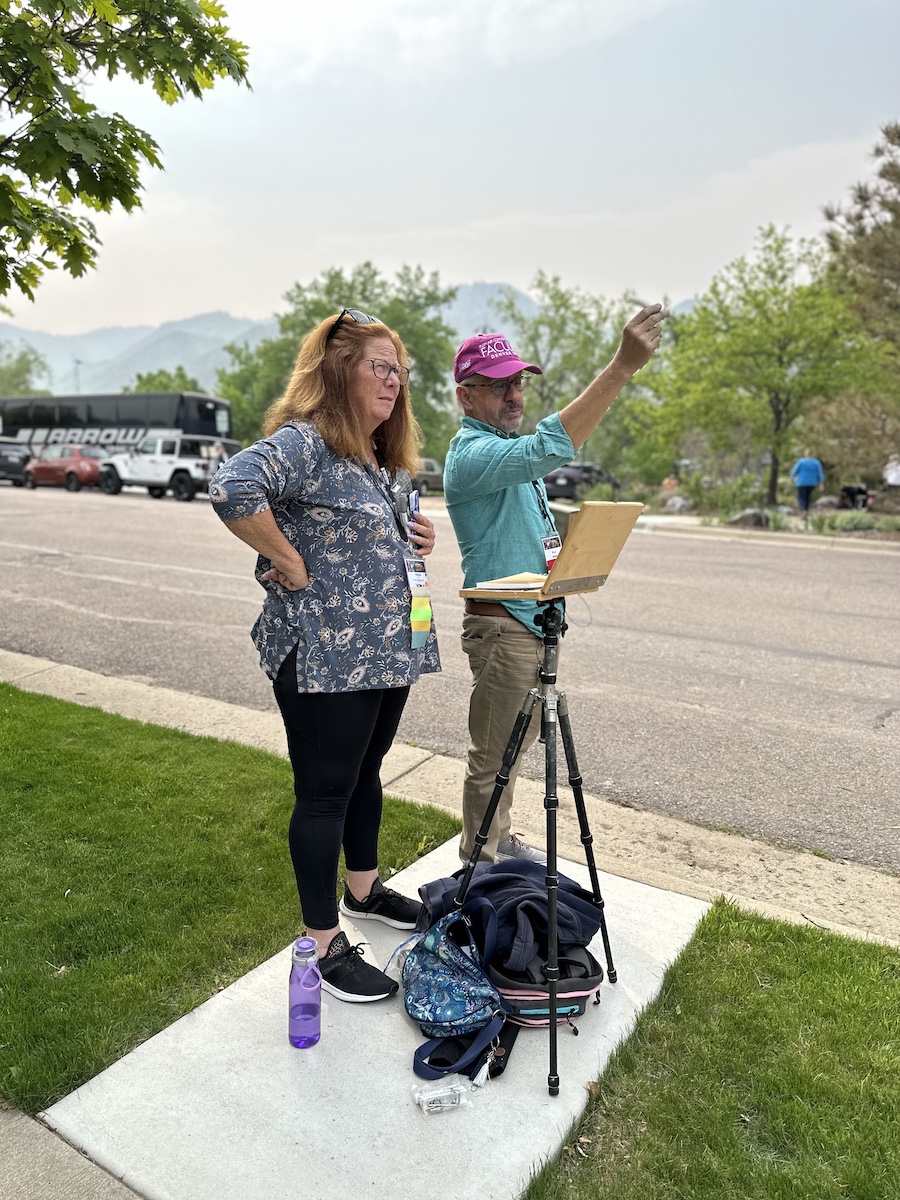

Different are the approaches of Paul Kratter and Bruce A. Gomez, who in the outdoor session acted as supervisors providing feedback to the participants.

Paul Kratter habitually starts with a sketch with which he divides the scene into 5-7 shapes on which he establishes tonal values based on four colors: white, black and two shades of gray.

Rich Gallego himself in the evening demonstration defined the shapes as the tonal masses that are the basis of the design.

In this phase, Kratter modifies and shifts the forms by transferring the sketches -which he keeps as his only reference in terms of defining light, which is constantly changing- on the board. From the dark masses he later derives the lighter values, observing the composition in the distance so as to see it as a whole and making changes if necessary, in a continuous back and forth. To finish, he refine the edges by adding small details.

The dynamic Bruce A.Gomez, who works in pastel and likes to depict waterfalls establishes the perspective of mountains by helping himself with the color blue. A color he has been using successfully for almost fifty years and that he calls it : “the fruit of experience.”

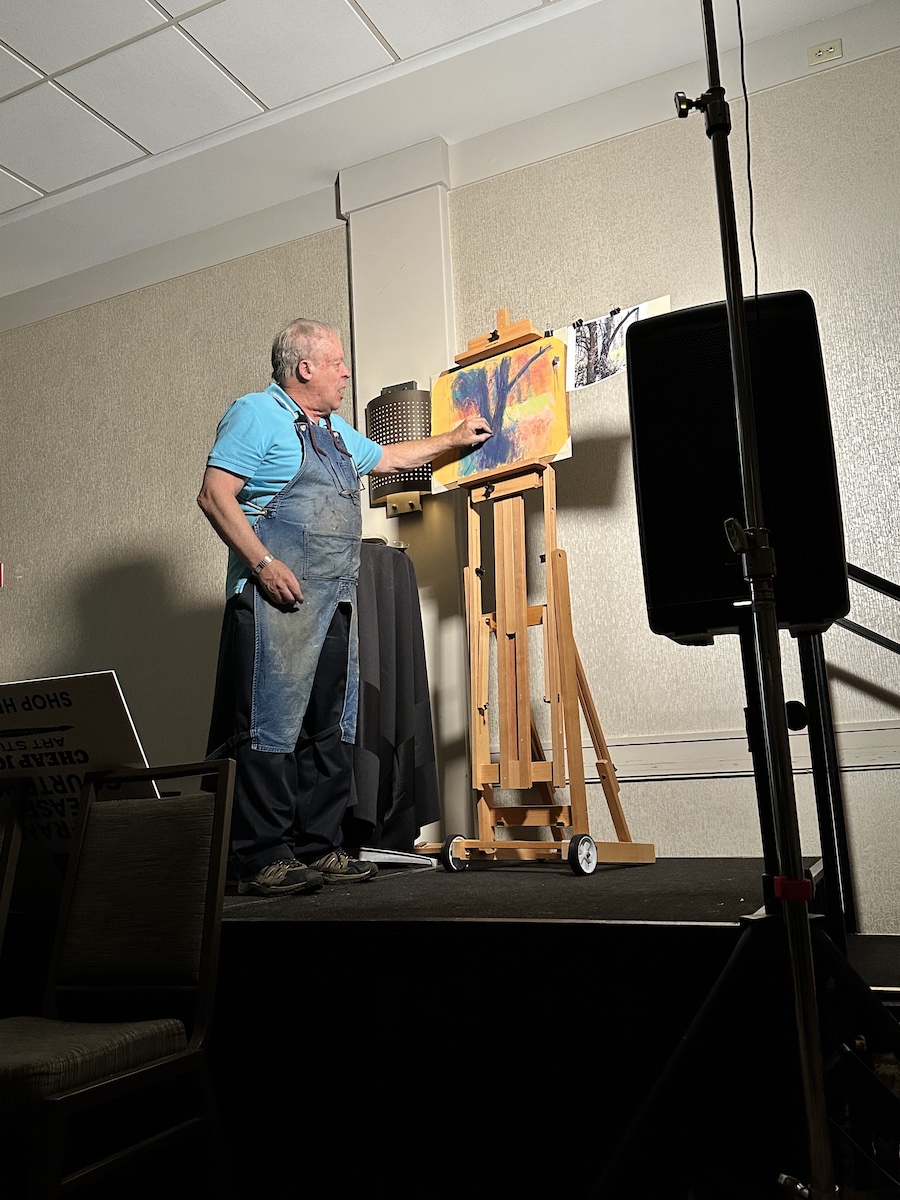

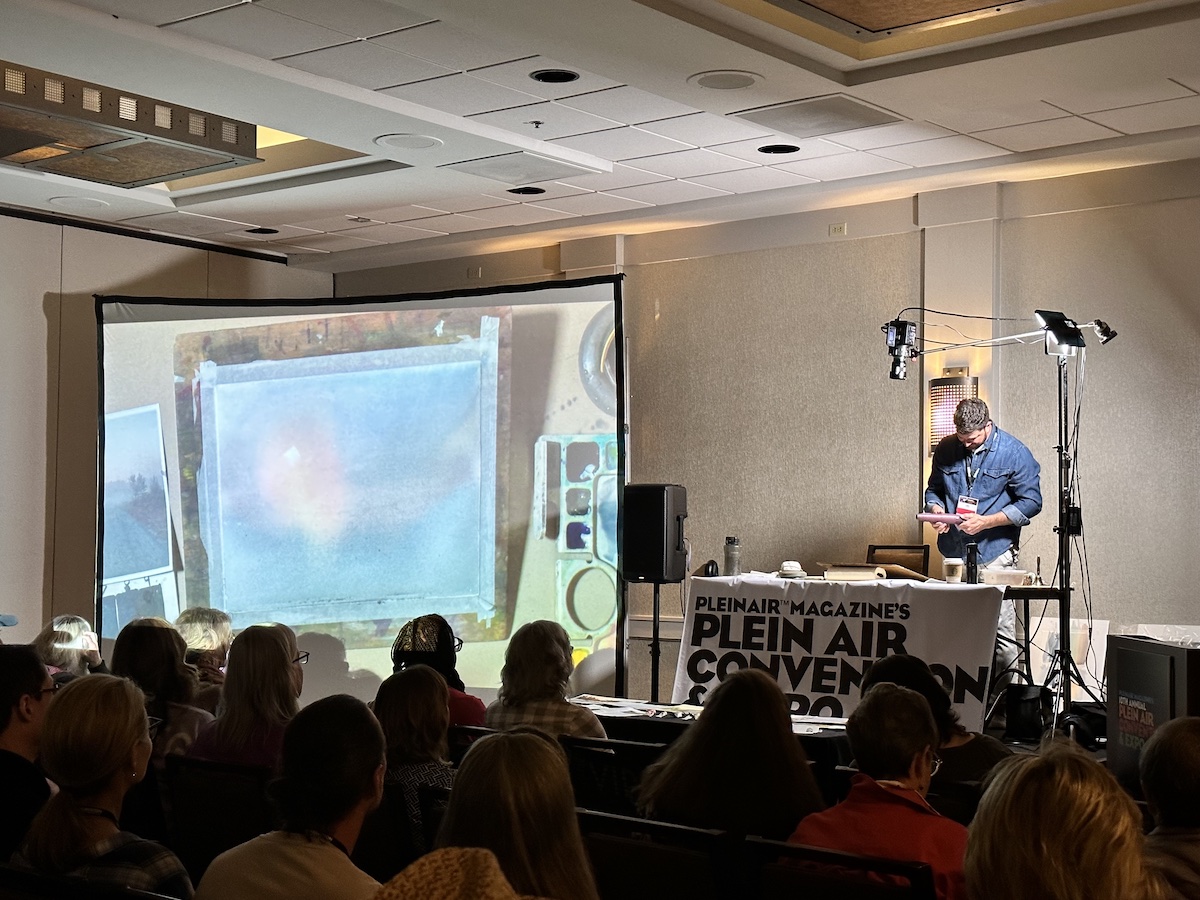

Buffalo Kaplinski in his watercolor demonstration begins with the arrangement of blue with which he defines the shadows, contrasting with the white of the paper with which he highlights the snowy peaks creating atmosphere.

For Doug Dawson, depicting mountain landscapes is more complex than one might imagine because the visual stimuli are multiple and as the artist stated, “You don’t really learn where do you go until you start painting.”

Bypassing the composition of the mountains, artist Mark Felhman argues for the importance of shifting compositional elements, “If they work and they are able to make the composition more daunting feel free to do that,” the artist said.

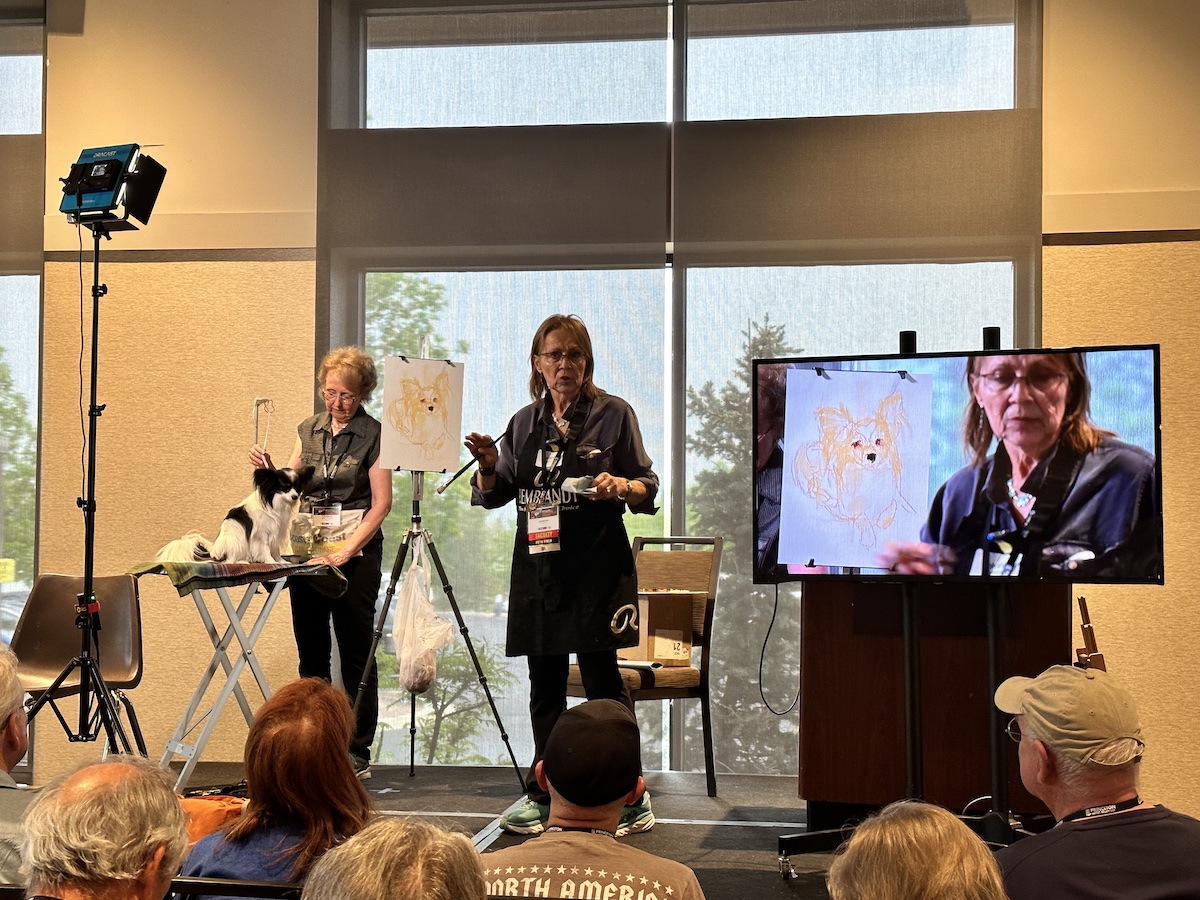

Demonstration sessions were not limited to the representation of the mountains that characterize the landscape, among them, Johanne Mangi, known for her depiction of animals. She imprinted the composition from the definition of the eyes of the dog present in the studio. “Having realized the eyes I paint the other elements of the face through triangulation,” said Mangi whose skill in rendering animal fur is truly convincing.

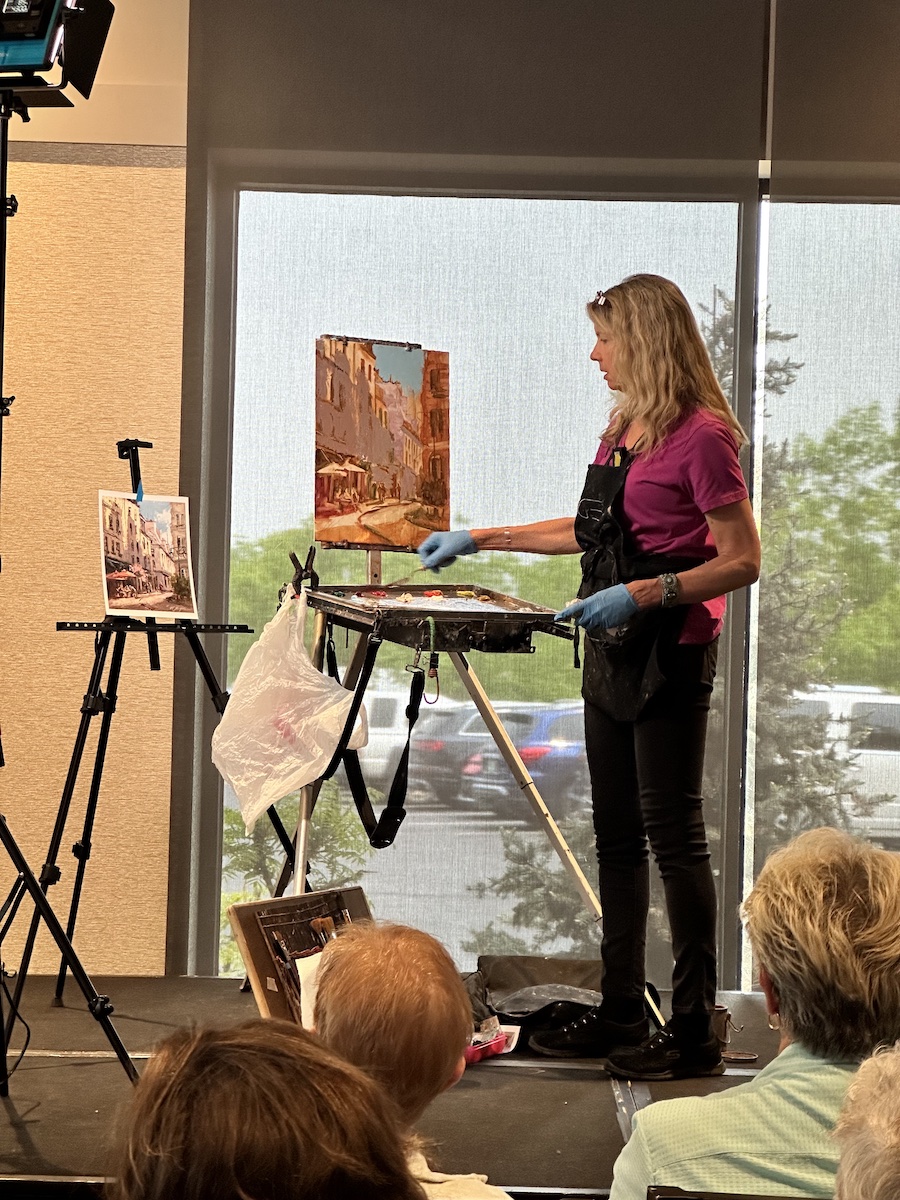

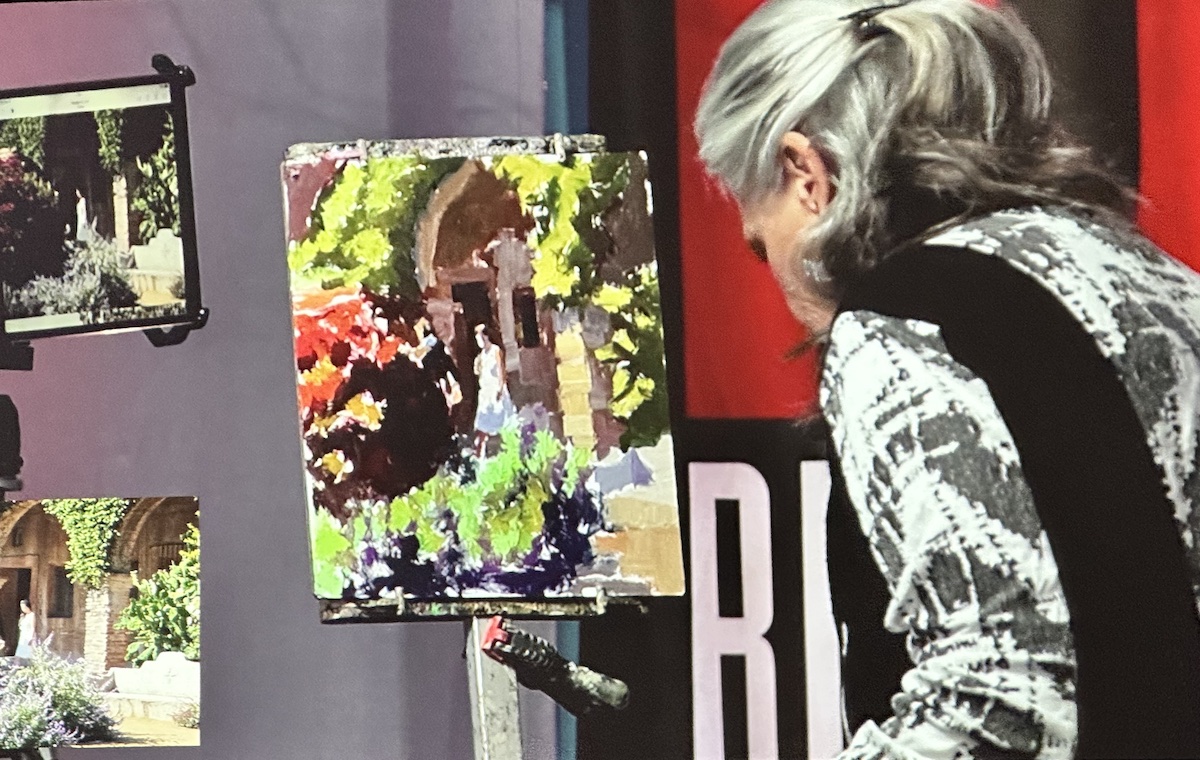

Michele Byrne, who mainly uses the palette knife with which she lays down dense layers of color, said how having a good attitude helps in the realization of the compositional process in which she likes to make straight lines that she drags poetically.

According to Charlie Easton the making of compositional sketches is a kind of homage to the place represented. His deep sense of observation has allowed him over time to refine the theory that complex landscapes require the simplification of forms in which the full communicative power of the composition is developed.

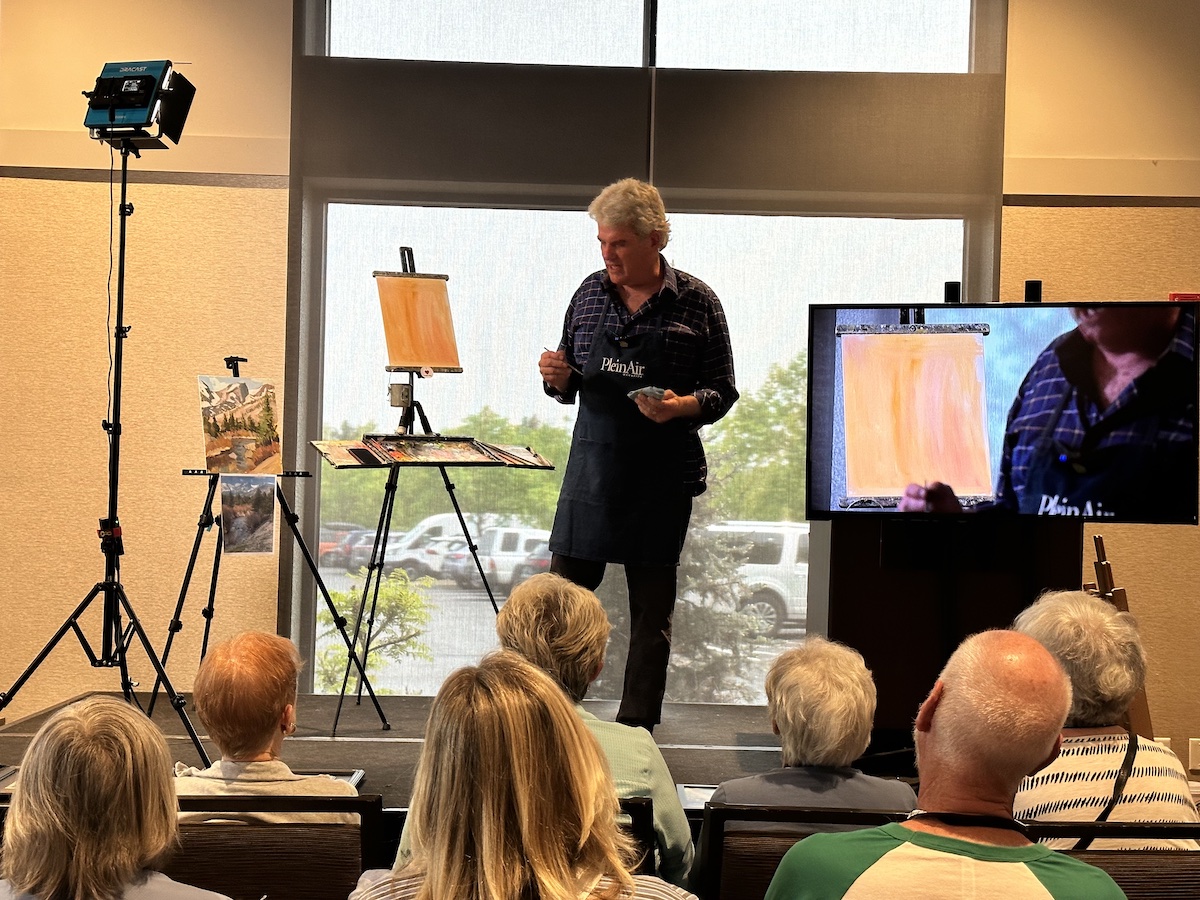

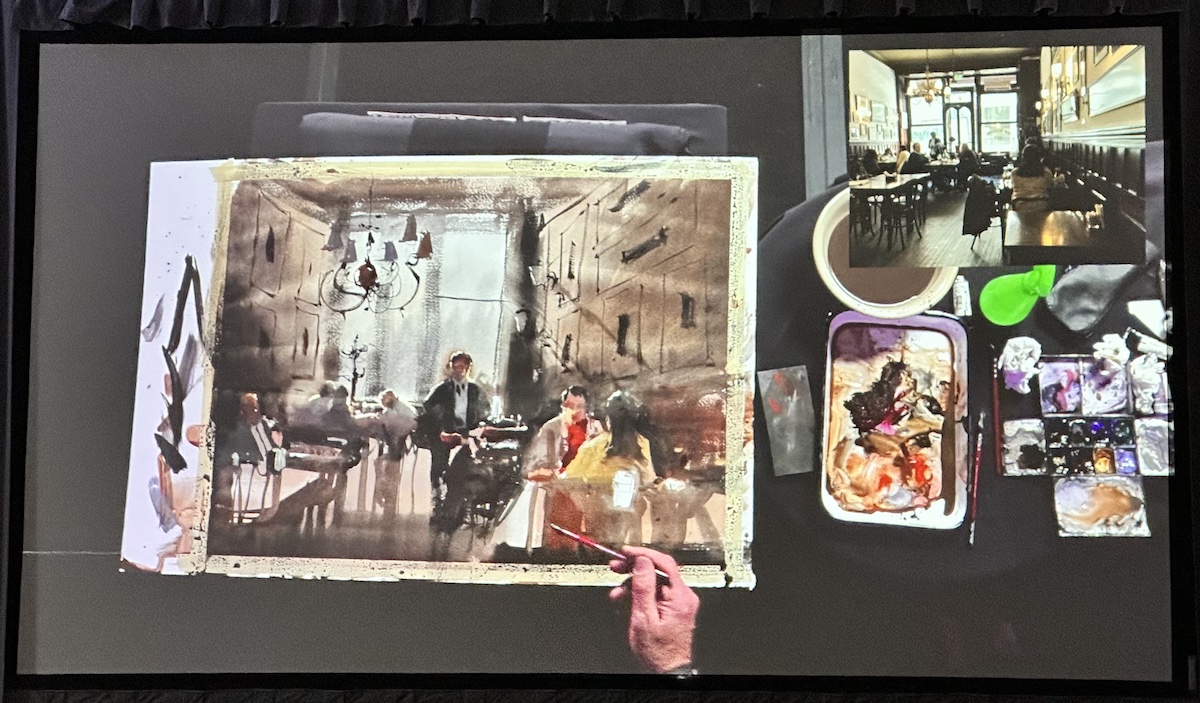

For watercolorist Alvaro Castagnet, who made the interior of a room in which the figurative presence is defined but not in detail, painting is not only technique but is a combination of poetry and spirit of communion with the place, which merge powerfully from abstract forms that he defines on finishing with the details of the focal point.

For Gail Sibley, composition derives from a process based on three key points: observation, reflection, and delving into the compositional process by which she relates elements.

For Dan Mondoloch, the information session was interspersed with the humor with which he directed participants through his compositional process.

Known as one of the foremost colorists, artist Camille Przewodeck, who was one of Eric Rhoads’ first teachers, created a demo based on colors that vary with the time of day and weather conditions. “Don’t worry about composition before you have to know how to create form and take advantage about the fact that more you practice more you understand the principle.” said the artist.

As with any self-respecting convention, there was no shortage of historical input offered on the day by Jean Stern, art historian and director emeritus of the Irvine Museum, who specializes in the history of California Impressionism.

Interweaving historical information with slides with which he showed the works of some famous artists, more or less recent, devoted to plein-air painting, Stern highlighted how the history of plein-air painting developed in America in water-rich areas on which light plays a fundamental role. Among them California-home to LPAPA, Laguna Plein Air Painters Association, dedicated to the preservation of impressionistic painting in Laguna Beach, CA- and Florida, in which artists defied the dangers of nature in the Everglades to capture pristine landscapes.

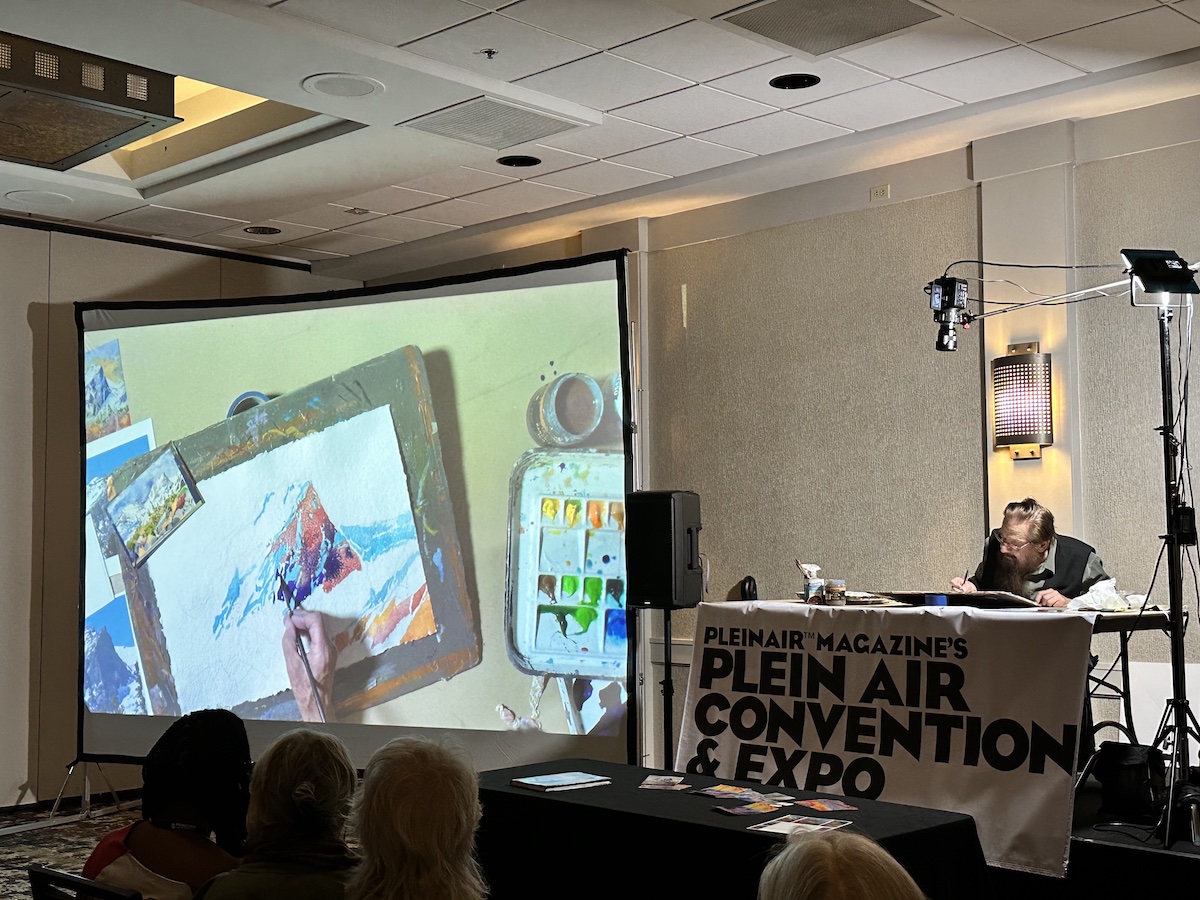

Finally, there was no shortage of artists who through demonstration sessions offered by the sponsors of the event highlighted some key points of their artistic process, among them Vladislav Yeliseyev -for Cheap Joe’s Art Stuff- who stated how in watercolor there are only two friends: the masking tap, which has to protect the characteristic edges of the paper from the color and the paper cloth with which he doses the amount of water and consequently of pigment to put on the composition.

In his demonstration for Golden Artist, artist Greg Watson presented Pan Pastels, the brand recently acquired by Golden Artist: a new way to approach pastel that is laid down, with special tools, in bright, pigment-rich strokes.

The day has come to an end and Miami Niche looks forward to seeing you tomorrow for another exciting day spent between demonstration sessions and plein air painting in Eldorado State Park.